Articles

- The world of the Romantics 1770 - 1837

- Romantic writers

- Key events

- Making sense of the tangible world

- Making sense of the intangible world

Impact of the French Revolution

The French Revolution of 1789

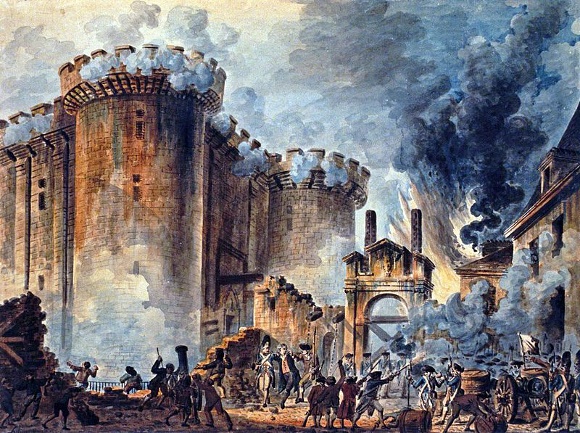

The French Revolution and the fall of the Bastille in July 1789 had an enormous impact on British public opinion in England and influenced the terms on which political debate would be conducted for the next thirty years.

The settlement of 1689 and the British Constitution

The settlement of 1689 and the British Constitution

Since the constitutional settlement of 1689, which balanced the powers of Parliament and the monarchy, the British system of government had enjoyed support across the political spectrum and was much admired by observers from other countries. This system gave distinct roles in the process of governance and legislation to:

-

The Crown

-

The House of Lords

-

The House of Commons

It was felt to combine the best aspects of monarchical, aristocratic and democratic modes of government. It was believed that this combination of forces worked to offset the dangers inherent in allowing any one of them to predominate:

-

Monarchy could easily degenerate into tyranny

-

Aristocracy could degenerate into oligarchy, or the concentration of power in a ruling elite

-

Democracy could become anarchy and the rule of the mob

If anything occurred to upset the balance, such as the emergence of corrupt practices in appointments to political offices, the system would work to restore equilibrium.

The growth of political dissent

By the 1760s, however, this consensus of opinion was beginning to break down. There had been political dissent earlier in the eighteenth century but it had tended to object to and seek to remedy abuses of the system without questioning the system itself. In the 1760s and 1770s, various strands of radical political opinion began to question the basis on which the British Constitution was founded:

-

It was argued that democracy was only partial and that this limited the representativeness of the House of Commons.

-

The right to vote, as well as being granted only to men, depended on a property qualification, thus excluding the great mass of the population.

-

Religious dissenters, including Roman Catholics as well as members of nonconformist sects, did not enjoy such full voting rights as were available. Because MPs were required to swear an oath of conformity to the Church of England, religious dissenters were not eligible for election to public office.

The road to reform

Attempts to introduce Parliamentary reform in 1809, 1818, 1821 and 1826 were defeated in the House of Commons. It was only in 1832, the year after the revised edition of Frankenstein was published, that the Reform Act, with a major extension of the Parliamentary franchise, was passed into law. The Test and Corporation Acts, removing most of the political restrictions on religious dissenters, had been repealed in 1828, and the Roman Catholic Emancipation Act followed in 1829.

Richard Price

In 1789, Richard Price (1723-91), a Welsh dissenting minister who had supported the American Revolution, published Discourse on the Love of Our Country. In this work, he argued that the Revolution of 1789 represented an improvement on the 1689 settlement in the following areas:

-

Matters of the liberty of conscience

-

The right to resist abuses of power

-

The right to choose and dismiss governments

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (1729-97) was the son of an Irish Protestant lawyer and his Roman Catholic wife. He also studied law, and became a politician and man of letters. His work An Enquiry into the Origins of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1757) was extremely influential in the formation of aesthetic taste in relation to the natural world:

Edmund Burke (1729-97) was the son of an Irish Protestant lawyer and his Roman Catholic wife. He also studied law, and became a politician and man of letters. His work An Enquiry into the Origins of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1757) was extremely influential in the formation of aesthetic taste in relation to the natural world:

-

He argued against the way in which the House of Commons was dominated by the King and his supporters

-

He spoke and wrote on behalf of Roman Catholic emancipation

-

He supported the American Revolution

The French Revolution, however, horrified Edmund Burke:

-

In Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) he refuted Richard Price's argument that the people had the right to dismiss the elected government and form a new one, and he appealed to the lessons of history in support of his view

-

He believed that society was an organism rather than a purely administrative or legislative mechanism

-

He thought that the revolutionaries in France were atheists who had offended against history by overthrowing the monarchy

When he was in France in 1773, he had seen Queen Marie Antoinette; she had come to represent for Burke all that was sacred in the principle of monarchy, and he wrote a eulogy of her in Reflections. For Burke, then, the principles of the 1689 English settlement remained the best basis for government.

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (1737-1809) was born in Norfolk, his father a Quaker and his mother an Anglican. He emigrated to America in 1774 after being dismissed from his job as an excise officer for seeking an increase in pay. He worked on behalf of American independence and served in Washington's army, fighting against British troops. He returned to England in 1787 and published the two parts of The Rights of Man in 1790 and 1792 as a direct response to Burke's Reflections:

-

He advocated the idea of fundamental ‘inalienable rights' that should be enjoyed by all human beings

-

He challenged Burke's notion of society as a binding contract between the past, present and future, and argued that for society to progress towards greater freedom and justice it was vital to break free from the chains of the past

The Reign of Terror and disillusion with the Revolution

Excitement among those who had welcomed the French Revolution turned to disillusion. The years 1793-4, beginning with the execution of Louis XVI in January 1793, saw bitter conflicts in France as different political groups fought for supremacy. During the ‘Reign of Terror', thousands of people from all parties were executed in Paris and elsewhere in the country.