Articles

- Poetry: Recognising poetic form

- Historical aspects

- Stylistic aspects

Heroic couplets

Definition

The heroic couplet consists of a pair of rhymed decasyllables (i.e. lines of ten syllables), almost always in the metric form of the iambic pentameter. Its origins are usually traced to the work of Geoffrey Chaucer (c.1343-1400), for instance in the opening lines of The Canterbury Tales (from c. 1387):

Whan that Aprill with his shores soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour.

Elizabethan drama and poetry

Shakespeare and his contemporaries also made use of the heroic couplet, sometimes as a form for whole plays and speeches, but also at the end of a speech or poem to give added point and weight to the final lines:

The weight of this sad time we must obey:

Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.

The oldest hath borne most: we that are young

Shall never see so much nor live so long.

(King Lear, 1605, Act 5, sc.iii, 344-7)

So long as men can breathe or eye can see,

So long lives this and this gives life to thee.

(Sonnet 18, l.13-14)

Augustan flowering

The great age of the heroic couplet came in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, especially in the work of John Dryden (1631-1700) and Alexander Pope (1688-1744).

Dryden

Dryden used it with great power in both plays and poems. His verse moves at a steady pace and gives weight and authority to his satire, as in these lines on his political enemy, the Earl of Shaftesbury (whom he calls Achitophel):

A name to all succeeding ages cursed;

For close designs and wicked counsels fit;

Sagacious, bold, and turbulent of wit;

Restless, unfixed in principles and place;

In power unpleased, impatient of disgrace.

(Absalom and Achitophel, 1681)

These lines show how skilfully Dryden manipulates alliteration, linguistic inversion, expressive punctuation, rhythm and the balance of ideas to achieve his effects.

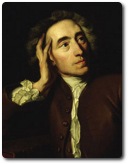

Pope

Pope's purposes were also mostly satirical, but his verse is more lively, sociable and quick-witted than Dryden's. He is adept at the compelling use of word order, syntax, metre and the balance of the elements of both line and couplet, but there is something more sharp and sparkling about his wit, which can make Dryden seem ponderous and slow by comparison. Even when writing about serious matters such as the practice of literary criticism, Pope's lines are fleet, nimble and pointed:

Pope's purposes were also mostly satirical, but his verse is more lively, sociable and quick-witted than Dryden's. He is adept at the compelling use of word order, syntax, metre and the balance of the elements of both line and couplet, but there is something more sharp and sparkling about his wit, which can make Dryden seem ponderous and slow by comparison. Even when writing about serious matters such as the practice of literary criticism, Pope's lines are fleet, nimble and pointed:

And, without sneering, teach the rest to sneer;

Willing to wound and yet afraid to strike,

Just hint a fault and hesitate dislike.

(Prologue to the Satires: An Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot, 1735, 201-4)

His portrait of a heartless woman in the second of his moral essays is similarly biting. Here he makes dramatic use of the material markers of an elegant life, exposing the shallowness of a social world full of possessions, but lacking in values:

Can mark the figures on an Indian chest;

And when she sees her friend in deep despair,

Observes how much a chintz exceeds mohair!

(Moral Essays, Epistle 2: To a Lady, 1735, 167-70)

Demise

Other eighteenth century poets made extensive use of the heroic couplet, and it remained the dominant poetic form until the Romantic poets emerged at the turn of the century. Some nineteenth century poets continued to make use of the form but by the twentieth it had effectively disappeared from English poetry.