Articles

- Drama developments

- Mystery and morality plays

- The earliest permanent theatres

- Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre design

- Female roles before 1660

- Restoration theatre

- Commedia dell’Arte

- Eighteenth century theatre

- Nineteenth century melodrama

- Naturalism and realism

- Twentieth century experiments

- Later twentieth century theatre

- Literary features of Elizabethan drama

Eighteenth century theatre

Historical background

The Hanoverian or Georgian age

When the last Stuart monarch, Queen Anne, died childless in 1714, the British crown should have passed to Princess Sophia of Hanover, one of the Protestant granddaughters of King James I. Unfortunately, Sophia died in the same year as Anne, so Parliament invited Sophia’s eldest son, George, Duke of Hanover to become King George I of England and Ireland.

George, who was Queen Anne's closest living Protestant relative, came to the throne as the first monarch of the House of Hanover. Although over fifty Roman Catholics had closer blood relationships to Queen Anne, the Act of Settlement that had been passed by Parliament in 1701 prohibited Catholics from inheriting the British throne.

The Georgian period includes the reigns of four Hanoverian Kings: George I (1714-1727); George II (1727-1760); George III (1760-1820) and George IV (1820-1830).

A time of growth and change

The eighteenth century, sometimes referred to as the Age of Reason or the Enlightenment, was a time of great social and cultural change. The development of rational and scientific approaches to religious, social, political, and economic issues led not only to the American Revolution (1772) and the French Revolution (1789) but also marked the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, which established Britain as a major world power with a global Empire.

The population of Britain grew rapidly during this period, from around five million people in 1700 to nearly nine million by 1801. Many people left the countryside in order to seek out new job opportunities in rapidly expanding towns and cities, whilst many immigrants also arrived from large areas of continental Europe.

Famous writers of the period include novelists Henry Fielding, Mary Shelley and Jane Austen; Romantic poets Lord Byron, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge and men of letters such as Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift and Samuel Jonson.

English theatre during the eighteenth century

The eighteenth century was the great age of theatre. In London and the provinces, large purpose-built auditoriums were built to house the huge crowds that flocked nightly to see plays and musical performances. A variety of entertainments were on offer, from plays and ballets to tightrope-walkers and acrobats. Theatre began to establish itself as an art form not only for the sophisticated upper classes, but for all levels of society.

The new playhouses

The growth of theatres

At the beginning of the Restoration, Charles II had granted licences for only two theatre companies in London. By the end of the eighteenth century the number had risen to seven:

At the beginning of the Restoration, Charles II had granted licences for only two theatre companies in London. By the end of the eighteenth century the number had risen to seven:

- The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

- Lincoln’s Inn Fields

- The Queen’s Theatre, Haymarket

- The Little Haymarket Theatre

- Goodman’s Fields

- Sadler’s Wells

- The Royalty

Extensions to Drury Lane and Lincoln’s Inn Fields meant that they could hold audiences of three thousand people at each performance.

Staging

At the beginning of the century some boxes were still placed alongside the stage and the forestage or apron was still quite large. As the number and size of the theatres and audiences grew, stages were redesigned so that the long forestage or apron of Restoration times was shortened and pushed back almost to the proscenium arch. The separation between stage and audience was further emphasised by placing the members of the orchestra in front of the stage in an area known as the orchestra pit.

Scenery

In order to make scenes appear more vivid, as well as give added depth and perspective to the stage, designers began to paint scenery on parallel wings, also known as flats, which receded from the audience. This also made it easier and faster for stage hands to change a setting, as the wings for later settings rested behind one another. When a scene change was needed, the stagehands simply removed the flat and placed it at the rear.

Lighting

At the beginning of the century the auditorium was as brightly lit as the stage. As theatre design developed, the stage was further separated from the audience by making the auditorium dark during a performance, so that footlights and sidelights could be used to light up the actors on stage. Lighting was originally by means of candles and candelabra but these were replaced with kerosene lamps and gas lamps later in the century. All methods of stage lighting at this time could be dangerous and accidents were quite common.

Acoustics

The size and overall structure of the theatres and stages contributed to the effect and efficiency of the acoustics. Theatres designed with an oval shape helped to ensure that acoustics were good and the proscenium arch helped prevent audience noise from submerging the lines of the actors. Theatres with arched ceilings above the stage also helped to boost the amplification of the play.

Audiences

Theatre-going was a very different experience from that of today and actors often had to fight to capture the attention of the audience, which could be rude, noisy and sometimes even dangerous.

Going to the theatre was a social event and audiences were a mixture of both rich and poor, who sat in different parts of the theatre depending on whether they could afford cheap or expensive tickets. The upper class patrons usually sat in boxes so that they could see and be seen, while the lower classes were squeezed into hot and dirty galleries at the top of the building.

Alcohol and food was consumed in great quantity; people arrived and left throughout the performance; playgoers often chatted amongst themselves and sometimes pelted actors with rotten fruit and vegetables. Rioting at theatres was also not uncommon. The Drury Lane theatre was destroyed by rioting on six occasions during the century.

Early plays and playwrights

Richard Steele

From 1714 to 1718 Steele was supervisor of the Drury Lane theatre. He wrote mostly comedies and was one of the first playwrights to move away from the Restoration style by developing a new form of sentimental drama; a form which Oliver Goldsmith described as drama where ‘the virtues of private life are exhibited, rather than the vices exposed’.

From 1714 to 1718 Steele was supervisor of the Drury Lane theatre. He wrote mostly comedies and was one of the first playwrights to move away from the Restoration style by developing a new form of sentimental drama; a form which Oliver Goldsmith described as drama where ‘the virtues of private life are exhibited, rather than the vices exposed’.

Sentimental drama was popular with the rising middle-class audience because it tended to treat them seriously, in ways which neither comedy nor tragedy did.

More on Richard Steele: As well as writing some of the first plays of the new age, Steele was also the first writer to produce and edit a twice-monthly theatrical journal called The Theatre. He was co-founder of The Tatler magazine and was also associated with The Spectator and The Guardian - publications which are still in print today.

Nicholas Rowe

Rowe was a barrister who became a poet and a renowned playwright. (picture) He was a friend of both Alexander Pope and Joseph Addison and wrote historical or romantic tragedies which were mainly performed at Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Rowe was a barrister who became a poet and a renowned playwright. (picture) He was a friend of both Alexander Pope and Joseph Addison and wrote historical or romantic tragedies which were mainly performed at Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

More on Nicholas Rowe: Rowe’s plays were very dramatic and highly acclaimed. The principal role in Tamerlaine (1702) was written for Thomas Betterton; The Fair Penitent (1703) was a great success for Elizabeth Barry and later for Sarah Siddons, who also played the lead in The Tragedy of Jane Shore (1714)

In 1709 Rowe edited and produced a complete edition of Shakespeare’s plays, which he divided into acts and scenes with added stage directions. Rowe also became Poet Laureate in 1715 and was honoured by his burial in Westminster Abbey.

John Gay

Gay made and lost several fortunes, had a dubious reputation, a very indulgent lifestyle and wrote The Beggar’s Opera (1722), probably the most successful musical play of the century. The idea for Gay’s masterpiece was suggested to him by Jonathan Swift. It is not, strictly speaking, an opera, but a play with songs, possibly the first example on the English stage of what is now called ‘musical theatre’. Gay wrote the libretto and the music (over sixty popular ballads) was arranged by John Pepusch, a German born composer and contemporary of Handel.

Gay made and lost several fortunes, had a dubious reputation, a very indulgent lifestyle and wrote The Beggar’s Opera (1722), probably the most successful musical play of the century. The idea for Gay’s masterpiece was suggested to him by Jonathan Swift. It is not, strictly speaking, an opera, but a play with songs, possibly the first example on the English stage of what is now called ‘musical theatre’. Gay wrote the libretto and the music (over sixty popular ballads) was arranged by John Pepusch, a German born composer and contemporary of Handel.

More on The Beggar's Opera: The Beggar’s Opera satirised Italian opera and parodied the upper classes by comparing them with criminals. It enjoyed a record run at Lincoln’s Inn Fields and became one of the most successful plays of its time. Gay’s last play, a sequel to The Beggar’s Opera called Polly, was banned by Horace Walpole, the Prime Minister and was only produced forty years after Gay’s death.

Playwright Bertolt Brecht and composer Kurt Weill adapted Gay’s masterpiece in 1929 and renamed it The Threepenny Opera, giving the play a sharp political perspective. Their production reflected 1920s Berlin dance bands and cabaret and inspired modern musical theatre hits such as Cabaret and Chicago. The show's opening number, Mack the Knife became one of the most popular songs of the twentieth century.

More on John Gay: The epitaph on John Gay’s tomb in Westminster Abbey sums up the poet, essayist, playwright and librettist whose life was full of incident and seldom dull:

Life is a jest and all things show it: I thought so once - and now I know it.

Five of Gay’s seven stage plays were flops. One in particular, Three Hours After Marriage (1717), which was written in collaboration with fellow Scriblerus members Alexander Pope and John Arbuthnot, led to a fist fight backstage between Gay and the leading man, Colley Cibber.

Like many of his contemporaries, Gay was a poet, essayist and playwright and one of the founder members of the Scriblerus Club in London.

More on the Scriblerus Club: The club was founded in 1713 by writers Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, John Gay, Thomas Parnell and John Arbuthnot. The name Scriblerus was a reference to ‘scribler’, a term of contempt at the time for a writer with no talent. The club’s purpose was to satirise and ridicule writers who used over-exaggerated language to make themselves seem to be highly educated but only made themselves appear ridiculous in the attempt. The group created a fictitious character called Martinus Scriblerus and collaborated on the production of witty articles supposedly written by him, that were published as The Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus in 1742.

Actors, actresses and actor-managers

The organisation of eighteenth century theatre

Theatre companies led by actor-managers had begun during the Restoration era and continued during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. An actor formed a theatre company, chose the plays he wanted to produce, played the leading roles in them and managed the company's business arrangements.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the actor managers had been replaced, first by stage managers and later by directors.

Colley Cibber

Cibber was a playwright and poet who was actor-manager of Drury Lane theatre from 1703-32. (picture) His play Love’s Last Shift; or, The Fool in Fashion (1696) is generally considered to be the first sentimental comedy, a form of drama that dominated the English stage for nearly a century. The playwright John Vanbrugh honoured it with a sequel, The Relapse: or, Virtue in Danger (1696), in which Cibber’s character Sir Novelty Fashion became Lord Foppington.

Cibber was a playwright and poet who was actor-manager of Drury Lane theatre from 1703-32. (picture) His play Love’s Last Shift; or, The Fool in Fashion (1696) is generally considered to be the first sentimental comedy, a form of drama that dominated the English stage for nearly a century. The playwright John Vanbrugh honoured it with a sequel, The Relapse: or, Virtue in Danger (1696), in which Cibber’s character Sir Novelty Fashion became Lord Foppington.

More on Colly Cibber: Cibber produced a famous adaptation of Shakespeare’s Richard III, which remained as the preferred acting version of that play for over a century. He also wrote an adaptation of Molière’s Tartuffe, renamed The Non-Juror (1717), and an acclaimed theatrical autobiography, Apology for the life of Mr Colley Cibber, Comedian (1740). His last stage appearance was in 1745, when he played the lead in his own adaptation of Shakespeare’s King John.

David Garrick

The legendary actor-manager David Garrick made his London stage debut playing Richard III at the Goodman's Fields Theatre in East London on 19 October 1741 and was an overnight sensation because of his revolutionary and exciting naturalistic acting style.

The legendary actor-manager David Garrick made his London stage debut playing Richard III at the Goodman's Fields Theatre in East London on 19 October 1741 and was an overnight sensation because of his revolutionary and exciting naturalistic acting style.

Under Garrick’s management theatrical techniques such as scenery, costumes and lighting were improved and significantly developed. In 1771, Garrick hired a French painter, Phillip de Loutherbourg to work on scenic design at Drury Lane. Loutherbourg created elaborate sets that gave the entire stage the illusion of being three dimensional. He did this with the use of multi-level scenery and stage lighting that faked the appearance of moonlight, flames and other natural elements. Loutherborg was the first set designer to use scrims and coloured lighting.

More on David Garrick: In the autumn of 1747 Garrick took over the management of Drury Lane Theatre in partnership with James Lacy, the former stage manager of Covent Garden. Over the next twenty nine years Garrick established Drury Lane as the finest repertory theatre in Europe. As an actor, Garrick was equally at home playing tragedy or comedy. As a writer, he adapted Shakespeare, wrote or co-authored original plays and appeared in works written by contemporary playwrights. As manager, Garrick maintained a strong company of fine actors and demanded strict adherence to his instructions and rules.

The Kemble dynasty

The Kembles were a family of actors and actresses based in London who were famous from the late eighteenth to the mid nineteenth century. The founders of the dynasty were the actor and theatre manager Roger Kemble (1722-1802) and his wife, the actress Sarah Ward (1735-1807). They were parents of the actress Sarah Siddons (1735-1831), the actor John Philip Kemble (1757-1823), the actor and theatre manager Stephen George Kemble (1758-1822), and the actor, theatre manager and playwright Charles Kemble (1775-1854).

The Kembles were a family of actors and actresses based in London who were famous from the late eighteenth to the mid nineteenth century. The founders of the dynasty were the actor and theatre manager Roger Kemble (1722-1802) and his wife, the actress Sarah Ward (1735-1807). They were parents of the actress Sarah Siddons (1735-1831), the actor John Philip Kemble (1757-1823), the actor and theatre manager Stephen George Kemble (1758-1822), and the actor, theatre manager and playwright Charles Kemble (1775-1854).

More on The Kemble dynasty:John (J.P.) Kemble

JP Kemble specialised in playing Shakespearian tragic heroes, building his character slowly to an emotional climax, rather than choosing to play a role in an extravagantly emotional way. In his later career, as actor-manager of Drury Lane and Covent Garden, he was noted for using costumes and scenery that made productions more believable.

Sarah Siddons

Like her brother John, Sarah Siddons (née Kemble) was famous for playing tragic heroines and never played a comic part in her entire acting career. Siddons learned to act in her father’s touring repertory company. In 1774 she was engaged by Garrick to perform at Drury Lane, but her inexperience led to her dismissal and she spent a further six years touring the provinces.

She returned to the London theatre in 1782 in Garrick's adaptation of The Fatal Marriage, where she became an instant success. Over the next twenty years, at Drury Lane and later in Covent Garden, Sarah Siddons became the most famous actress of the age. Her tall figure and stunning looks, together with her extraordinary dramatic talent led to a form of mass hysteria when she was on stage. Her farewell performance in her signature role as Lady Macbeth literally stopped the show. The audience was so moved after the sleepwalking scene that the play was brought to an end; the curtain was closed and re-opened a few minutes later for her emotional farewell speech.

Fanny Kemble

The daughter of Charles Kemble and niece of Sarah Siddons and JP Kemble, Fanny was the youngest member of the Kemble dynasty and became an acknowledged actress in both comic and tragic roles. Her first appearance on stage was as Juliet in William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet at Covent Garden Theatre. She played all the principal women's roles of the time and her beauty and personality made her a great audience favourite.

In 1832, Kemble accompanied her father on a theatrical tour of the United States and in 1834 she retired from the stage to marry an American, Pierce Butler. The marriage failed and after a brief return to the stage in America, Kemble returned to London and established a new career as a writer.

Edmund Kean

Kean was a foundling who grew up to be one of the greatest English tragic actors of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Kean specialised in strong evil roles which he played realistically, relying on his own forceful personality and on sudden changes of voice and facial expression.

Kean was a foundling who grew up to be one of the greatest English tragic actors of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Kean specialised in strong evil roles which he played realistically, relying on his own forceful personality and on sudden changes of voice and facial expression.

More on Edmund Kean: Kean joined a touring company in Kent when he was fifteen and spent ten hard years developing his acting skills on the road. During this time he became a heavy drinker and his behaviour was often violent and unpredictable.

His appearance in 1814 as Shylock, in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, caused a sensation, as he played against type. Traditionally, Shylock had been portrayed as a comic character, but Kean played him as an evil, embittered man, carrying a butcher’s knife.

Though Kean was always admired as an actor, his unpredictable public behaviour made him increasingly unpopular and the last eight years of his life were damaged by alcohol and other excesses. Kean collapsed onstage during a performance of Othello, playing the lead opposite his son, Charles in 1833 and died penniless. Charles Kean went on to become a well-respected actor-manager during the Victorian era.

Later eighteenth century plays and playwrights

Oliver Goldsmith

Goldsmith was an Irishman who was a playwright, novelist, poet and essayist. (picture) He came to England in 1756 and initially made his living as a journalist, writing articles for journals and periodicals. Goldsmith’s novel The Vicar of Wakefield (1776) is one of his best known works, along with the narrative poem The Deserted Village (1770).

Goldsmith was an Irishman who was a playwright, novelist, poet and essayist. (picture) He came to England in 1756 and initially made his living as a journalist, writing articles for journals and periodicals. Goldsmith’s novel The Vicar of Wakefield (1776) is one of his best known works, along with the narrative poem The Deserted Village (1770).

Goldsmith wrote one libretto for a musical work called The Captivity (1764) and only two plays for the stage; The Good-Natur'd Man (1768) and the brilliant comedy She Stoops to Conquer (1773). Both were in sharp contrast to the popular sentimental dramas of the time and played to full houses. She Stoops to Conquer was first produced by George Colman at Covent Garden and it remains one of the most significant stage comedies of the eighteenth century, still performed today.

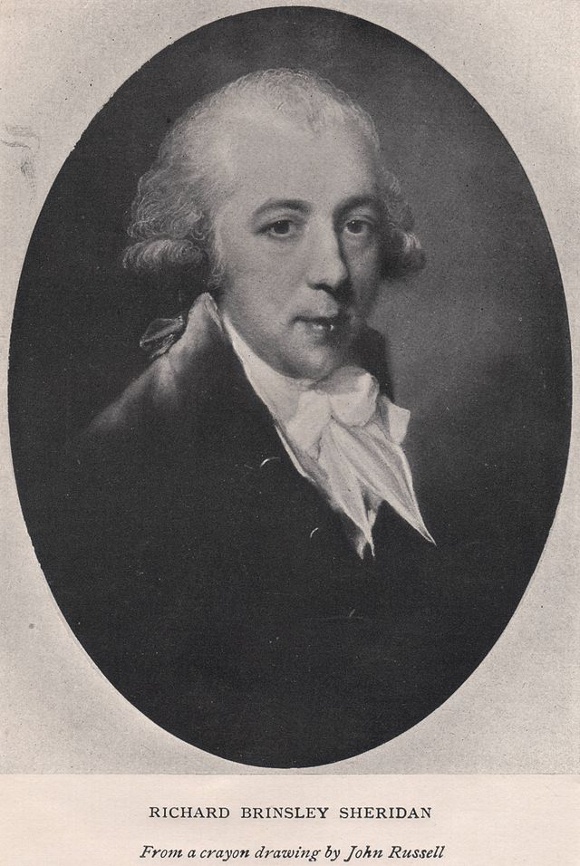

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Sheridan’s first play, The Rivals (1775), was written for production at Covent Garden and at first was not well received. However, after a number of rewrites, the play became an enormous success and is still regarded as a comic masterpiece.

Sheridan’s first play, The Rivals (1775), was written for production at Covent Garden and at first was not well received. However, after a number of rewrites, the play became an enormous success and is still regarded as a comic masterpiece.

Sheridan’s work is witty and sophisticated, with finely drawn characters, clever plots and none of the crudeness or cruelty of plays written during the Restoration. Two of his finest plays, The Rivals and The School for Scandal (1777) are regarded as the best examples of the eighteenth century comedy of manners and both are deservedly part of the English classical theatre repertoire.

As manager of Drury Lane, Sheridan encouraged the development of Loutherbourg’s scenic designs, writing spectacular pantomimes, scenes for harlequinades and a comic opera.

More on pantomime and harlequinade: British pantomime has very deep roots, drawing on the traditions of Commedia dell'Arte for its assortment of stock characters and conventions. The harlequinade was originally a silent mime act with music and stylised dance, which provided the comic closing part of a longer evening of serious entertainment. By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the harlequinade was performed at the end of the first act as part of a spectacular transformation scene before the interval.

More on Richard Brinsley Sheridan:

Sheridan was born in Dublin where his father was a theatre manager. The family moved to England where Sheridan intended to study law. However, he was forced into a career change, becoming a playwright after he eloped with his future wife Elizabeth Linley and fought two duels on her account.

In 1776 Sheridan joined with his father-in-law Thomas Linley in 1776 to buy a half share in Drury Lane Theatre for £35,000. On Garrick’s death in 1779, Sheridan and Linley obtained outright ownership of Drury Lane and Sheridan’s later plays were written for performance there.

Sheridan gave up writing for the stage in 1779 and became a successful politician. As a Member of Parliament for Stafford, he was a frequent speaker in the House of Commons and became one of the best orators in Britain.

A new style of theatre for a new age

Victorian melodrama

Queen Victoria’s reign, from 1837 to 1901, ushered in a period of peace, prosperity and growth which by the beginning of the twentieth century saw Britain established as a major industrial power with a global Empire that ruled over a quarter of the world's population.

The sentimental comedies of the eighteenth century continued to be performed in the early part of the century but the mood of the times was beginning to change and one of the results of this was the development of a new theatrical genre called melodrama.

Melodrama’s exciting fantastical drama and exaggerated acting styles, combined with the increasingly sophisticated stage machinery of Victorian theatres, suited the times very well and met an ever increasing audience’s demands for spectacle and mass entertainment.