Dubliners Contents

The impact of the past: from the eighteenth century to 1904

The eighteenth century Protestant Ascendancy

From the success of William III in 1691 onwards, Protestant settlers in Ireland flourished. Land was confiscated from William’s opponents and given to the victors. Penal laws meant that Catholics could not vote, hold political office or even worship openly. They were barred from buying land and forced to subdivide their estates on death equally between all heirs. This resulted in smaller and smaller divisions, until land-holdings became untenable. Over the next century, the percentage of land held in Catholic ownership declined from 22% to 14%, then to 5%.

Meanwhile, the increasingly Protestant Parliament started to meet regularly and determine its own policy, though it still could not introduce legislation that was not already passed by Westminster. Trade with Britain and her colonies flourished, and increased national pride was seen in the establishment and elegance of Dublin institutions and domestic architecture. However, there was huge resentment that a tariff was imposed on Irish goods yet not on English goods (whereas Scotland had a free trade agreement with England) and the food produced for export was frequently at the expense of feeding the native population.

The rising of 1798 and Wolfe Tone

In the revolutionary fervour of the late eighteenth century, antagonism towards the dominance of England increased, even amongst Protestants, who now considered themselves Irish rather than British ‘colonial administrators’. Henry Grattan commanded a ‘patriot army’ and in 1782 concessions were granted that freed up trade and allowed greater legislative power to Ireland. After the Pope dropped his opposition to the Hanoverian monarchy in 1766, many of the anti-Catholic penal laws were gradually amended so that Catholics could start to prosper.

In the revolutionary fervour of the late eighteenth century, antagonism towards the dominance of England increased, even amongst Protestants, who now considered themselves Irish rather than British ‘colonial administrators’. Henry Grattan commanded a ‘patriot army’ and in 1782 concessions were granted that freed up trade and allowed greater legislative power to Ireland. After the Pope dropped his opposition to the Hanoverian monarchy in 1766, many of the anti-Catholic penal laws were gradually amended so that Catholics could start to prosper.

However, these concessions did not go far enough for many. Wolfe Tone was a leading Protestant agitator who founded the United Irishmen to gather both Catholics and Protestants in a reform movement to achieve independence from Britain. This became an armed rebellion in 1798, in which he also enlisted revolutionary French help. However, like many previously, the rebellion was brutally suppressed, with ongoing reprisals against all involved. Although Tone was captured, he committed suicide rather than face an English gallows, becoming the first notable martyr for the Irish republican cause.

Act of Union 1801

The British answer to the United Irishmen’s rebellion was to close down the Irish Parliament and unite Ireland with Britain with the 1801 Act of Union. It was hoped that this would secure better rights for Catholics and enhanced status for Ireland, enabling it to be represented more fully at Westminster etc. However, the loss of autonomy was deeply resented by both Protestant and Catholic Irish, whilst moves for full Catholic emancipation were blocked by the British monarch, George III. The necessity for Irish MPs and Lords to be in London led to the neglect of many large estates, absentee Protestant landlords simply charging high rents but doing nothing to advance the conditions of their (mainly) Catholic tenants.

The rising of 1803

The desire to overturn the 1801 Act of Union became a rallying cause for most of the Irish population. In 1803 Catholic sympathiser Robert Emmet led an ill planned uprising, again trying to enlist French help (against whom the British were fighting). Although the rebellion was a fiasco, Emmet’s oratory was remembered and inspired future republican agitators after he was hung, drawn and quartered.

Daniel O’Connell

Daniel O’Connell was from a previously wealthy Catholic family and trained as a barrister, becoming a noted orator. In 1823 he set up the Catholic Association to campaign for reform in land ownership, the Church of Ireland Tithe tax, tenants’ rights and economic reform, all of which had penalised Catholics. In 1828 he became an M.P. but, as a Catholic, could not take his seat in Westminster. Using peaceful mass rallies, he campaigned for full Catholic emancipation and, once this was achieved in 1829, he set up the Repeal Association working for a repeal of the 1801 Act of Union using the same methods. O’Connell died in 1847 after his health was weakened by a period of imprisonment.

The Fenians

O’Connell was noted for his refusal to countenance violence and was prepared to work with the political establishment to achieve his ends. However, the Young Irelander movement sought for total separation from Britain by means of armed rebellion, fuelled by anger at the British failure to remedy the effects of the great Irish famine of 1845-7. Whilst an uprising in 1848 failed, those aspirations were continued by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB, est. 1856) and its American counterpart, the Fenian Brotherhood. This was set up in 1858 amongst the Irish emigrants to America, who funded and supported IRB agitation back in the United Kingdom from the 1860s right through to the establishment of Irish Home Rule in the 1920s.

Home Rule

From the 1870s onwards, Irish politics was dominated by the fight for Home Rule – the fight for Ireland to govern itself, independent of Britain and the British government. Initially home rule was regarded political self-representation for domestic affairs, whilst allowing the UK to administer Ireland’s role in imperial affairs. However, more radical elements of the movement agitated for complete disassociation from Britain. Although British Prime Minister Gladstone appealed for the passing of his Irish Home Rule bills of 1886 and 1893, he was defeated, creating further dissatisfaction amongst Home Rule supporters.

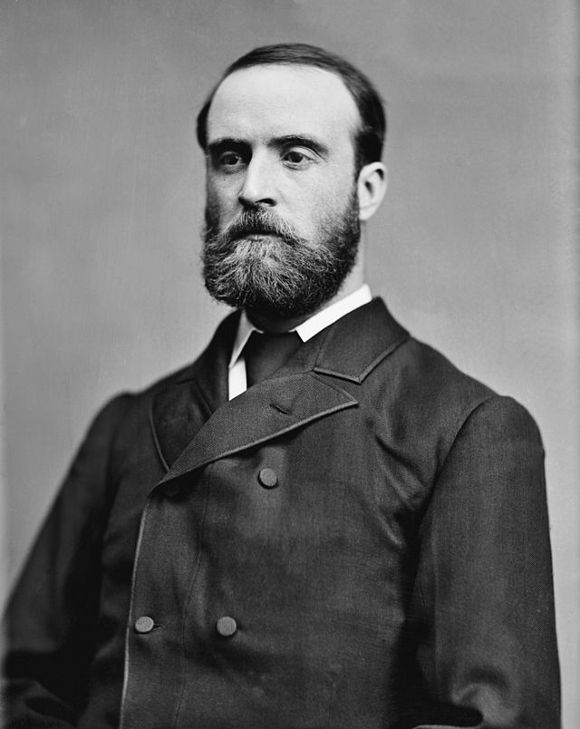

Charles Stewart Parnell

In Ireland, the campaign for Home Rule was headed by Charles Stewart Parnell, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. Parnell was well respected by both the Irish and the British (the British Government was cooperating with Parnell’s home rule campaign up until the First World War, when all other politics took a back seat).

In Ireland, the campaign for Home Rule was headed by Charles Stewart Parnell, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. Parnell was well respected by both the Irish and the British (the British Government was cooperating with Parnell’s home rule campaign up until the First World War, when all other politics took a back seat).

In 1890, however, Parnell’s career and reputation were ruined due to the O’Shea divorce case, in which it was revealed that Parnell had been having a long term affair (and had fathered children with) Kitty O’Shea, the estranged wife of Captain William O'Shea. The O’Sheas had been separated for a while before Parnell started his relationship with Kitty. However, he lost support, as most of his adherents were Catholic and opposed to extra-marital sex and divorce and re-marriage.

Parnell figures in Ivy Day in the Committee Room (see Synopses and commentary). Despite Parnell’s fall from grace, some of the politicians in the story are nostalgic for Parnell’s strong leadership and hard work in fighting for Home Rule.

Although Dubliners was composed between 1904-6, Irish political thinking of the time was already fermenting what would result in an armed stand against the English ten years later (the Easter Rising of 1916). This led to the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922, followed by the Irish Civil War.

Recently Viewed

Scan and go

Scan on your mobile for direct link.