Articles

- Drama developments

- Mystery and morality plays

- The earliest permanent theatres

- Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre design

- Female roles before 1660

- Restoration theatre

- Commedia dell’Arte

- Eighteenth century theatre

- Nineteenth century melodrama

- Naturalism and realism

- Twentieth century experiments

- Later twentieth century theatre

- Literary features of Elizabethan drama

Naturalism and realism

Historical background

A change in attitude

What is usually understood as modern theatre began to develop from the middle of the nineteenth century, when new philosophical ideas of realism and naturalism replaced the subjective traditions of the Romantic Movement. As a result, a stage style that had remained virtually unchanged for a century and a half underwent a radical shift.

Romanticism had been the predominant artistic movement in Europe from the late eighteenth century onwards, with an intense focus on the consciousness of the individual in terms of imagination, emotion and an intense appreciation of the beauties of nature.

However, by the middle of the nineteenth century, the Romantic emphasis on emotion over reason and of the senses over intellect had given way to a much more objective and scientific way of examining the human condition. A number of factors contributed to this:

- A year of revolutions in France, Germany, Poland, Italy, and the Austrian Empire during the so-called Springtime of the Peoples in 1848 showed that there was a widespread desire for political, social, and economic reform

- Technological advances in industry and trade led to an increased belief that science could solve human problems

- The working classes were determined to fight for their rights, using unionisation and strikes as their principal weapons

- Romantic idealism was rejected in favour of pragmatism

- The common man demanded recognition and believed that the way to bring this about was through action.

These factors helped fuel the development of two major philosophical ideas, realism and naturalism, which resulted in a radical shift in theatrical presentation.

Realism and naturalism

Theatrical definitions

The terms realism and naturalism are closely linked but there are significant differences in what they mean in the theatre:

- Realism describes any play that depicts ordinary people in everyday situations

- Naturalism is a form of realism that particularly focuses on how technology and science affect society as a whole, as well as how society and genetics affect individuals.

Realism

Beginning in the early nineteenth century, realism was an artistic movement that moved away from the unrealistic situations and characters that had been the basis of Romantic theatre. The playwright Henrik Ibsen is regarded as the father of modern realism because of the three-dimensional characters he created and the situations in which he put them. People in the audience could relate to the activities occurring on stage and the individuals involved.

Beginning in the early nineteenth century, realism was an artistic movement that moved away from the unrealistic situations and characters that had been the basis of Romantic theatre. The playwright Henrik Ibsen is regarded as the father of modern realism because of the three-dimensional characters he created and the situations in which he put them. People in the audience could relate to the activities occurring on stage and the individuals involved.

Naturalism

Charles Darwin, in his book The Origin of Species theorised that only the fittest of any natural species would survive to pass on its genetic material. Thus in drama a naturalistic focus addresses subjects in a scientific manner. The writer becomes a disinterested party who observes and studies specimens as though in a laboratory.

Convergence and divergence

Similarities between realism and naturalism

- Realistic and naturalistic plays depict events that could happen in real life, maybe even to members of the audience.

- Both genres focus on individuals and families in everyday situations.

- During the late 1800s and early 1900s, playwrights found ample subject matter for both genres as the sciences advanced and people struggled and fought against oppressive governing systems.

Differences between realism and naturalism

- Naturalism approached art in a more scientific, almost clinical, manner than realism

- Realistic plays often had characters to whom the audience could relate and sympathise

- Naturalistic plays, which were difficult to create and rarely popular, approached every element with the detachment of a scientist

- Realistic plays could show characters breaking free from difficult situations and allow the audience to empathise with their plight.

- Naturalistic works, on the other hand, sought only to study the situation, characters and other factors without interpretation.

As time went on, the two genres blended together so as to make it very difficult to classify plays as either completely naturalistic or totally realistic. Elements of both could and did exist alongside one another.

Naturalism and realism in France

Writers, practitioners and plays

Emile Zola (1840-1902)

Zola defined the naturalist movement in the preface to his novel Thérèse Raquin (1867). He stated that the writer's task was to dissect human nature and the environment with the clinical precision of a scientist. Zola’s stage adaptation of Thérèse Raquin (1873) served as model for theatrical naturalism and influenced other French playwrights such as Henri Becque and Jean Jullien.

Zola defined the naturalist movement in the preface to his novel Thérèse Raquin (1867). He stated that the writer's task was to dissect human nature and the environment with the clinical precision of a scientist. Zola’s stage adaptation of Thérèse Raquin (1873) served as model for theatrical naturalism and influenced other French playwrights such as Henri Becque and Jean Jullien.

Jean Jullien (1854–1919)

Jullien introduced the famous description of naturalistic drama as ‘a slice of life put onstage with art’ after his play The Serenade (1887) was staged in the Thèâtre Libre in Paris. He believed that the purpose of naturalistic theatre was make the audience think during the performance and after the play ended.

André Antoine and the Thèâtre Libre

Antoine was a French theatre director who championed the new naturalistic style of drama and founded the Thèâtre Libre (the ‘Free Theatre’) in 1887 to stage Zola’s Thérèse Raquin after the theatre group for which he previously worked had refused to do so.

Antoine was a French theatre director who championed the new naturalistic style of drama and founded the Thèâtre Libre (the ‘Free Theatre’) in 1887 to stage Zola’s Thérèse Raquin after the theatre group for which he previously worked had refused to do so.

The Thèâtre Libre had no censorship, which allowed it to stage plays that other theatres would not, such as Henrik Ibsen's Ghosts (1881), which had been banned in most of Europe.

Antoine's productions were famous for creating real-life settings on stage, using real props such as whole beef carcases, as well as sets which were totally accurate representations of rooms, complete with furniture and doors and windows that worked.

The set was called a box set and Antoine would often rehearse actors on stage with a temporary wall which he named the fourth wall that blocked off the stage from the auditorium. This would be removed for performances but having rehearsed ‘in the box’, the actors would play to one another, making the performance look and sound more realistic and natural.

As well as influencing dramatic development in France, Antoine’s work and ideas affected thinking all over Europe and this led to the founding of many other companies, such as:

- Jack Grein’s Independent Theatre Society in London in 1891

- Otto Brahm’s Freie Bühne (‘Free Stage’) in Berlin in 1889

- (perhaps the most famous of all) Nemirovich Danchenko and Konstantin Stanislavsky’s Moscow Art Theatre in Russia in 1898.

Naturalism and realism in Russia

The situation in Russia

Although the struggle for freedom and liberation was evident in many parts of Europe at the end of the nineteenth century, it was possibly strongest in Russia where the need to express the reality of the human experience led to a bloody revolution in 1917 which changed the country forever.

Russian playwrights followed the lead of other European writers in producing plays that took the everyday lives of the middle-class and the poor as subject matter for serious realistic dramas, while the first serious steps to codify realism in acting were made by Konstantin Stanislavsky for his productions at the Moscow Art Theatre.

Russian playwrights

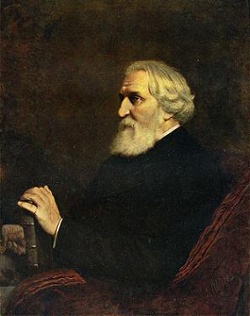

Ivan Turgenev (1818-1883)

Nikolai Gogol (1808-1852)

Gogol’s The Government Inspector (1836) was a satire on bureaucracy and the extensive political corruption that was deeply embedded in the government of Imperial Russia. The play satirised the failings of human greed and the stupidity of gullible people.

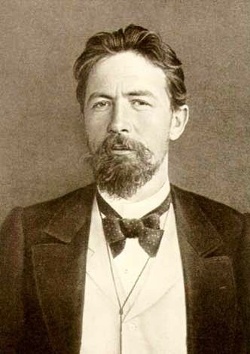

Anton Chekhov (1860-1904)

Chekhov believed that the role of the artist was to ask questions, rather than answer them. As a writer and doctor Chekhov understood the realities of lower-middle class and peasant life and his writing was objective and unsentimental. His short stories and plays are full of understatement, anti-climax, and implied feeling.

Chekhov’s first play, The Seagull (1895) had no starring role and dramatic action that did not build to a climax but declined with each act. The play’s first performance was a flop. Three years later, Chekhov was contacted by Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, co-founder along with Konstantin Stanislavsky, of the new Moscow Arts Theatre, which had been formed to encourage the new style of realistic drama. Danchenko persuaded Chekhov to let him revive The Seagull as part of the troupe's first season. The play was a huge success and from then on all Chekhov’s plays were staged by Stanislavsky and Danchenko and performed by the Moscow Arts Theatre actors.

Chekhov’s first play, The Seagull (1895) had no starring role and dramatic action that did not build to a climax but declined with each act. The play’s first performance was a flop. Three years later, Chekhov was contacted by Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, co-founder along with Konstantin Stanislavsky, of the new Moscow Arts Theatre, which had been formed to encourage the new style of realistic drama. Danchenko persuaded Chekhov to let him revive The Seagull as part of the troupe's first season. The play was a huge success and from then on all Chekhov’s plays were staged by Stanislavsky and Danchenko and performed by the Moscow Arts Theatre actors.

Chekhov pioneered what has been termed the ‘indirect action’ play, keeping a strict impression of realism. He employed understatement, broken conversation, off-stage events and absent characters as ways of creating dramatic tension. He also rejected the classical Aristotelian plot-line, in which ‘rising’ and ‘falling’ action comprised an immediately recognisable climax, catastrophe, and denouement.

In Chekhov's later plays - Uncle Vanya (1897), The Three Sisters (1901) and The Cherry Orchard (1904) - stage time was aligned with real time. It was the elapsed time between acts, sometimes extending over months or years, which showed the changes taking place in characters.

Chekhov’s work refined the whole concept of dramatic realism. His plays brought the essence of real life on to the stage, using characters and situations that were detailed, moving and delicate. Chekhov was one of the first great dramatic artists of modern times and his plays continue to endure as masterpieces of realistic theatre.

The practitioners

Stanislavsky, Nemirovich-Danchenko and the Moscow Art Theatre (1897)

Konstantin Stanislavsky (1863-1938) and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko (1858-1943) were co-founders of a progressive theatre company called the Moscow Art Theatre, set up in 1897 to stage realistic theatre performed by actors who were rigorously trained.

Nemirovich-Danchenko was a playwright, a theatre critic and an accomplished director who became instructor of dramatic art at the Moscow Philharmonic Society in 1891. As a teacher, Nemirovich-Danchenko had very strong ideas about theatrical art, the most important of which was the need for organised rehearsals, together with an acting style that allowed the actor to identify emotionally with the character being played.

Stanislavsky’s acting career began in his family’s amateur theatre group, called the Alekseyev Circle. Initially he was physically awkward, but he worked obsessively on his voice, diction, and body movement until he became the group’s central figure.

Stanislavsky’s acting career began in his family’s amateur theatre group, called the Alekseyev Circle. Initially he was physically awkward, but he worked obsessively on his voice, diction, and body movement until he became the group’s central figure.

Stanislavsky regarded the theatre as a socially significant art form with a very powerful influence on people. He believed that an actor must serve as the people’s educator and the only way to achieve this was by way of a permanent theatrical company which could train actors to a high level of acting skill. In 1888 he established a permanent amateur company called the Society of Art and Literature.

In 1891 Stanislavsky directed the company’s first major production, Leo Tolstoy’s The Fruits of Enlightenment. This was seen and admired by Nemirovich-Danchenko, who had followed Stanislavsky’s activities with great interest. The two men met in 1897 and outlined a plan for a new people’s theatre. Named the Moscow Arts Theatre, it was to consist of the most talented amateurs from Stanislavsky’s society and the best students of the Philharmonic Music and Drama School, which Nemirovich-Danchenko directed.

Nemirovich-Danchenko undertook responsibility for literary and administrative matters, taking care of the business side of the enterprise and choosing which plays should be peformed, while Stanislavsky was responsible for staging and production. The Moscow Arts Theatre became the centre where Stanislavsky developed his famous ‘System’ of acting. This was a series of ground breaking technical methods which have continued to shape acting practice to the present day.

The Stanislavsky System (a very short version)

The actor must:

- identify emotionally with the character

- understand the super objective of the character (the fundamental goal the character is aiming to achieve)

- understand the character’s personal objectives or motivation, moment by moment and scene by scene. This gives the actor the ‘through-line’ as the play progresses (the path to the ‘super-objective)

- understand the subtext (the inner life of the character)

- understand the given circumstances – the time, place, events – of the play

- use emotional recall to find the inner life of the character (be able to relate the actor’s own emotional experiences to the character being played).

(For more detail read The Complete Stanislavsky Toolkit by Bella Merlin, which is one of the standard practical texts for drama students.)

Beyond Chekhov

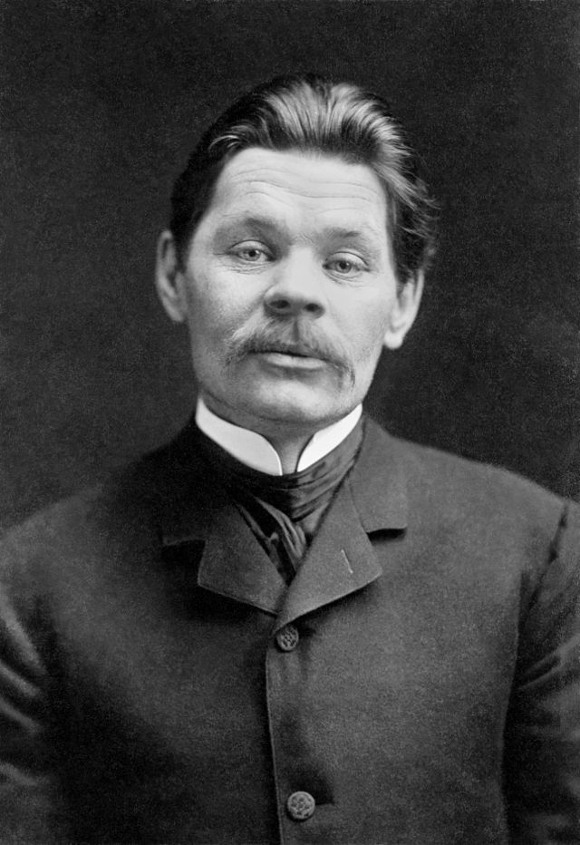

‘Maxim Gorky’ (1868-1936)

After Chekhov, the greatest writer of new realistic theatre in Russia was a playwright who chose to write under the pseudonym Maxim Gorky, because it translated as ‘Maxim the Bitter’. Alexei Maximovitch Peshkov Gorky came from a very deprived background and had first-hand experience of what life was like for the poorest Russian people.

After Chekhov, the greatest writer of new realistic theatre in Russia was a playwright who chose to write under the pseudonym Maxim Gorky, because it translated as ‘Maxim the Bitter’. Alexei Maximovitch Peshkov Gorky came from a very deprived background and had first-hand experience of what life was like for the poorest Russian people.

Gorky’s work was unsentimental and harsh; his view of the world was uncompromising. His plays such as The Philistines (1901) and Enemies (1906) dealt with injustice, violent crime, adultery and corruption and his view of the plight of those who lived on the margins of society was coldly realistic. During the revolutionary period after 1917 he spent many years in exile abroad, returning to Russia in 1923 and becoming an active supporter of the Soviet government. By 1934 he had been appointed President of the Union of Soviet Writers and continued to be a fervent supporter of Communism until the end of his life.

Naturalism and realism in Europe

Henrick Ibsen (1828-1906) Norway

Henrick Ibsen was born in Norway and learned his trade working as an assistant theatre manager and writing stage plays that were based on Norwegian folk legends. From 1863 he spent much of his life touring in other parts of Europe, living and writing some of his most celebrated plays in Italy and Germany before returning home to Norway in 1891, where he spent the rest of his life.

Together with Chekhov, Henrick Ibsen is regarded as one of the great writers of the period and a master of many dramatic genres. From early work in the form of epic poetical drama, he moved to naturalistic plays, then into symbolic naturalism and finally into absurdist surreal drama.

Ibsen’s work was creative and showed a very deep insight into human nature. He wrote about themes that were deeply shocking to audiences of the time, such as women’s rights; the nature of sin; the horror of being alone and abandoned; sexual frustration; corruption and the abuse of power.

More on the plays of Ibsen:

Early drama – folk stories, historical plays and epic poetical dramas

- The Feast at Solhaug (1855)

- The Pretenders (1864)

- Brand (1864) A five act verse tragedy about a priest which examines freedom of will and man’s relationship with God

- Peer Gynt (1867) a verse play with a similar central idea and incidental music written by Edward Grieg

Naturalistic drama

- Pillars of Society (1877) A play about lies and deceit in business and the use and abuse of power

- A Doll’s House (1897) One of Ibsen’s most significant naturalistic plays dealing with nineteenth century attitudes to marriage and the role of women in a male dominated society. The play was very controversial because at its end, Nora, the wife, leaves her husband and children in order to discover herself

- Ghosts (1881) The play’s shocking themes of free love, prostitution, hypocrisy, heredity, incest and euthanasia caused huge controversy when the play was first performed.

Symbolic naturalistic drama

- The Lady from the Sea (1888) A symbolic play about marriage and the choices and conflicts between love and duty

- Hedda Gabler (1890) A play about a woman whose cold hearted, manipulative behaviour became a game played to escape the boredom of a pointless existence. Audiences were horrified and shocked by the play’s controversial themes and the brutal suicide at its conclusion

- The Master Builder (1892) A play about a middle-aged architect’s struggle to come to terms with the end of his career; his infatuation with a younger woman and the loss of his sexual ability. The sexual imagery in the play supposedly made it a favourite of Sigmund Freud, the psychoanalyst best known for his tendency to trace nearly all psychological problems back to sexual issues. It has also been suggested that the play was partly based on Ibsen’s own affairs in later life with younger women.

Absurdist/surrealist drama

- When We Dead Awaken (1899) Ibsen’s last play examined the struggle between art and life, a problem that had obsessed him throughout his career. An artist and his former lover meet again after many years apart and discover that their lives have been a living death without one another. The artist realises that art has been a poor substitute for love and symbolically, the ‘dead’ cannot come back to life. Their attempted reconciliation results in both of them dying in an avalanche.

August Strindberg (1848-1912) Sweden

As well as a large number of novels and short stories, August Strindberg wrote more than fifty works for the stage. His early naturalistic work was much admired by Ibsen and George Bernard Shaw, both of whom regarded him as a champion of the naturalistic movement.

As well as a large number of novels and short stories, August Strindberg wrote more than fifty works for the stage. His early naturalistic work was much admired by Ibsen and George Bernard Shaw, both of whom regarded him as a champion of the naturalistic movement.

In his preface to the play Miss Julie, Strindberg uses Darwin’s evolutionary theory of the survival of the fittest to suggest that the upper classes are doomed to be replaced by the more forceful lower classes. The preface was regarded as the first important definition of dramatic naturalism.

Like Ibsen, Strindberg’s plays developed across a number of genres over a long career but many of them are now mostly forgotten.

More on the plays of Strindberg:

His most important plays are outlined here.

Naturalistic drama

- The Father (1887) was an experimental naturalistic drama which was a modern version of the classical Greek tragedy of Agamemnon, using the Aristotelian unities of time and place. Strindberg wrote in a style he called ‘artistic-psychological writing’ and the play dealt with women's rights, marriage and sexual morality. The play was symbolic, using Darwinian theories to examine ideas about masculine heroism and feminine deceit

- Miss Julie (1888) was another of Strindberg’s examinations of sexuality and class. The play dealt with lust and power in its various forms. Miss Julie has power over her father’s manservant Jean, because she is upper-class. Jean has power over her because he is a man and does not care about aristocratic values. The count, Miss Julie's father (an unseen character), has power over both of them since he is a nobleman, an employer and a father. Over the course of the play, the struggle for control swings back and forth between the lovers until Jean convinces Miss Julie that the only way to escape is by committing suicide. The ‘fittest’ of the species, the male, survives and the weaker female is destroyed

- The Bond (1892) the last of Strindberg’s purely naturalistic plays, was a stark picture of a disintegrating marriage which was probably influenced by Strindberg’s own divorce.

Symbolic drama

- The Ghost Sonata (1907) Part of a collection called The Chamber Plays and written at the beginning of the Expressionist period, The Ghost Sonata is an abstract drama that explores ideas about life after death and the meaning of existence. Inspired by Beethoven’s musical sonatas, the play is not written in conventional acts, but in three movements, like a piece of music. Themes of life and death, salvation and destruction, truth and lies are revealed through dramatic leitmotifs and montage.

More on the Expressionist period: Expressionism in the visual, literary, and performing arts was a movement that began in France and Germany and developed during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In expressionism the artist tries to present an emotional experience in its most compelling form. The artist is not concerned with reality as it appears but with its inner nature and with the emotions aroused by the subject. Characters and scenes are presented in a stylised, distorted manner with the intent of producing emotional shock. The object was to create a totally unified stage picture that would increase the emotional impact of the production on the audience. Thus:

- The narrative line became a series of episodes rather than a structured plot

- Dialogue was fragmented and disjointed, sometimes sounds replaced words

- Sets became symbolic, often angled or distorted

- The stage was conceived as a space rather than a picture

- Spotlights were used to create acting areas and shift focus from one area to another.

The movement had a direct influence on the work of Bertolt Brecht and his development of Epic Theatre

George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) Ireland and England

The Anglo-Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1925 and over a writing career that spanned almost sixty years he acquired the reputation of being the one of the greatest English language playwrights.

The Anglo-Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1925 and over a writing career that spanned almost sixty years he acquired the reputation of being the one of the greatest English language playwrights.

Social analyst

Shaw was a socialist and a founder member of the Fabian Society, an organisation committed to using parliamentary means to encourage the gradual adoption of socialist policies by means of political reform rather than revolution. The Quintessence of Ibsenism was an essay commissioned by the Fabian Society and published in 1891. In the essay Shaw analysed the works of the Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen and discussed Ibsen's recurring topic of the strong character holding out against social hypocrisy. Shaw used the essay and other writings about Ibsen not only to clarify Ibsen’s work for the English public but also to encourage the English public to see the stage as a vehicle for social change.

More on the plays of Shaw:

Dramas of social injustice

It is impossible to classify Shaw’s work into one specific dramatic genre. His early work was certainly influenced by Ibsen and European naturalist writers as can be seen by the early collection of Plays Pleasant and Unpleasant (1898) which dealt with serious social issues, although the ‘pleasant’ works used comedy to communicate the moral messages.

- Widowers' Houses (1892) raised awareness of social problems and the exploitation of the working class by greedy slum landlords

- The Philanderer (1898) examined the relationship between the sexes

- Mrs Warren's Profession (1898) dealt with attitudes to prostitution and the limited employment opportunities available for women in Victorian Britain

- The Man of Destiny (1897) used an imaginary meeting between a young Napoleon and a mysterious woman to illustrate ideas of liberty, honour and reputation

- Arms and the Man (1894) dealt with the reality of war, idealism and reality, and class rivalry.

- Candida (1898) questioned Victorian notions of love and marriage and what a woman really desired from her husband

- You Never Can Tell (1897) was an amusing comedy of errors about men and women’s negotiations over independence and marriage.

Even though many of Shaw’s plays dealt with social injustice, they were always presented with wit and elegance and he aimed his arguments at the intelligence of his audiences, rather than at their emotions.

Shaw became one of England’s most prolific writers, producing over fifty plays for the stage, many of which were also adapted for the cinema:

- Caesar and Cleopatra (1898) was a stage play telling the story of the young Cleopatra’s love affair with Julius Caesar, as a clever ‘prequel’ of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra. In 1938 Shaw adapted the play for the cinema, winning an Oscar for Best Screenplay

- Pygmalion (1913) Shaw’s comic masterpiece about an English professor whose attempts to turn a Cockney flower girl into a duchess has one of the funniest scenes in English drama. The play was also filmed and later adapted into an immensely popular musical, My Fair Lady (1956; motion-picture version, 1964).

When Shaw won the Nobel Prize for Literature, the citation praised him for work

which is marked by both idealism and humanity... [and] ...singular poetic beauty.Many of Shaw’s plays have remained in the English repertoire because of his ability to write satisfying stories and create characters that are full of life. His work was characterised not only by a desire to examine the important social issues of the time but also by an obvious love of language; a talent for high comedy and a wickedly sharp sense of humour.

Conclusion

Naturalism had a significant effect on modern theatrical development, from its origins in the mid-nineteenth century until the present day. It affected the way that productions were staged, acted and presented although it was not the only movement that affected the way that audiences thought.

In the later work of writers such as Strindberg and Ibsen the effects of expressionism began to appear and by the start of the twentieth century, new technologies such as cinema and later television provided ways of perceiving and representing the world in a totally new way.