Articles

- Drama developments

- Mystery and morality plays

- The earliest permanent theatres

- Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre design

- Female roles before 1660

- Restoration theatre

- Commedia dell’Arte

- Eighteenth century theatre

- Nineteenth century melodrama

- Naturalism and realism

- Twentieth century experiments

- Later twentieth century theatre

- Literary features of Elizabethan drama

Later twentieth century theatre

Modernism and postmodernism

Background and context

The twentieth century was an age of change when political, sexual, social and artistic ideologies began to be questioned, resulting in a series of shifts in Western philosophical thinking that came to be defined as postmodernism. However, this was preceded by its opposite concept - that of modernism (sometimes referred to as modernity), which began during the Renaissance, reached its height during the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century and continued into the early part of the twentieth century.

Modernism

The concept of Modernism was based on the belief that there was a rational, scientific explanation for everything that existed, in a universe that had been created by a divine being called God. In other words, there were certain absolute truths, a reliable language with which to express them and a secure set of rules for an ordered life.

Of course, faith and science did not always coexist in harmony and there were disputes and tensions, but there was an overall sense of order and confidence and a certainty about the meaning of life. Humankind had an existence and a purpose, both of which could be explained. As the twentieth century progressed, however, that sense of certainty began to disappear, as the values and norms that had shaped the Western world for so long began to be challenged.

Challenges to rationalism

- Religious certainty began to diminish and the consensus of faith began to break down after the horrors of the Great War (1914-18)

- Class divisions, extreme poverty and social unrest led to increased political activism and (in Russia) to bloody revolution in 1917

- Economic collapse in Europe and the United States during the mid-1920s and early 1930s increased the gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’

- The rise of nationalism in Germany led to the barbarism, mass murder and genocide during Hitler’s brief rule in Europe during the Second World War (1939-45)

- Disillusionment grew within – and with - the Soviet Union after Stalin had turned Russia into a totalitarian tyranny

- The outwardly prosperous and affluent societies of Western Europe and the USA in the 1950s and 60s actually masked the spread of spiritual emptiness

- Racial and ethnic tensions, together with struggles for sexual and gender equality, caused at best social unrest and at worst war, famine or genocide in many parts of the world

- Rapid advances in science and technology, together with the development of cinema, television, computer technology and mass communication systems, turned the planet into a ‘global village’.

Postmodernism (the short explanation)

As a result of the social and philosophical shifts which challenged the order inherent in Modernism, there developed the contrary theory (now) called postmodernism. Briefly, it held that:

- There are no clear or fixed truths, only immediate sensory experiences (the only truth is what you feel, not what you believe)

- There is no ‘big story’ (also called a Meta-Narrative) that explains existence or gives it a purpose (see Nietzsche’s famous statement below)

- There is nothing outside of human life that provides a set of values by which to live that life (no set of rules for living); no framework of ‘good’ or ‘bad’

- We live in a world of images created by ourselves and those images do not provide any external explanation to give us a sense of ‘what it’s all about’

- The world is a place in which humans are largely engaged in the business of exercising power over one another

- The world is a violent place concerned with oppression and preservation of ‘the self’.

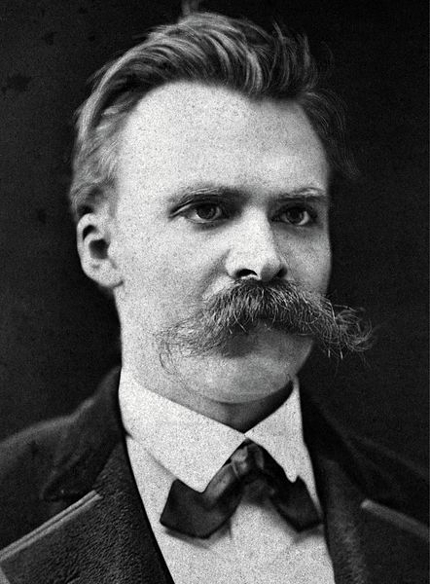

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche is credited with outlining the ideology that is now known in the Western world as postmodernism in his novel Thus Spake Zarathustra (1855). He is remembered for his dictums that: ‘there are no facts, only interpretations’ and that: ‘this old God liveth no more. He is dead indeed.’

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche is credited with outlining the ideology that is now known in the Western world as postmodernism in his novel Thus Spake Zarathustra (1855). He is remembered for his dictums that: ‘there are no facts, only interpretations’ and that: ‘this old God liveth no more. He is dead indeed.’

Modernism and postmodernism in the theatre

Effects on drama

The early part of the twentieth century was a time of great change in the theatre, when long established rules were challenged and many new forms of theatre were developed. It is important to remember that while some writers and practitioners had a burning desire to change their artistic world, others simply continued to produce well-crafted light entertainment. There was (and still is) an audience for both.

The continued popularity of the well-made play

In tune with the rational structure of modernism, the well-made play proved not only to be aptly named, but also very suitable as a means by which playwrights such as J B Priestley, Noel Coward and Terence Rattigan could find ways not only to entertain large mainstream (and mainly conservative) audiences, but also to inform and move them. As J B Priestley conveyed through An Inspector Calls (1946):

‘We don’t live alone. We are members of one body. We are all responsible for each other. And I tell you that the time will soon come when, if men will not learn that lesson, then they will be taught it in fire and blood and anguish.’

Noel Coward wrote plays and musical revues which embodied the moneyed and escapist world of the 1920s and 1930s. The Vortex and Fallen Angels were controversial plays about sexual promiscuity and drug addiction, but Coward also wrote comic plays like Blithe Spirit and Hay Fever, as well as a hugely successful ‘state of the nation’ pageant production called Cavalcade (1930). He also wrote popular songs and film scripts. Coward’s work held up a mirror to the time, reflecting the wit and the gaiety of his generation and his class. His style of writing, using wit that comes from character and situation, paved the way for later writers like Joe Orton and Alan Ayckbourn.

Noel Coward wrote plays and musical revues which embodied the moneyed and escapist world of the 1920s and 1930s. The Vortex and Fallen Angels were controversial plays about sexual promiscuity and drug addiction, but Coward also wrote comic plays like Blithe Spirit and Hay Fever, as well as a hugely successful ‘state of the nation’ pageant production called Cavalcade (1930). He also wrote popular songs and film scripts. Coward’s work held up a mirror to the time, reflecting the wit and the gaiety of his generation and his class. His style of writing, using wit that comes from character and situation, paved the way for later writers like Joe Orton and Alan Ayckbourn.

Terence Rattigan was a leading post-war playwright whose work, like that of his mentor Noel Coward, often dealt with homosexuality, either obliquely or by implication. Rattigan, like Coward, was homosexual and his plays feature characters who are repressed or suppressed and find the expression of emotion difficult. Before 1968 there was an absolute ban on homosexuality as a dramatic theme.

Terence Rattigan was a leading post-war playwright whose work, like that of his mentor Noel Coward, often dealt with homosexuality, either obliquely or by implication. Rattigan, like Coward, was homosexual and his plays feature characters who are repressed or suppressed and find the expression of emotion difficult. Before 1968 there was an absolute ban on homosexuality as a dramatic theme.

Experimental theatre also used dance, poetry and choric speech to create a new art form to express social criticism. Poets W H Auden and T S Eliot used verse plays to explore new ways of engaging with an audience through the ‘blood transfusion of poetry’.

The Theatre of the Absurd

The breakdown of modernist certainties started to be reflected dramatically in what critic Martin Esslin termed The Theatre of the Absurd. This was the title of his book written in 1961 about the work of a number of playwrights who wrote for the stage in the 1950s and 1960s. The term was taken from an essay by the French philosopher Albert Camus, who defined the human situation as basically meaningless and absurd.

Absurdist drama was strongly influenced by the traumatic experiences and the horrors of the Second World War. Universal truths and values became unstable and life was seen as insecure and meaningless. From 1945, the threat of nuclear annihilation also seems to have been an important factor in the rise of the new theatre, as was the fading of the religious dimension from contemporary life.

Some basic elements of Absurdist theatre

Absurdism openly rebelled against conventional theatre and was sometimes called ‘anti-theatre’ because its form was surreal and illogical, without conventional plot or conflict. It can be recognised by all or some of the following:

- Language becomes meaningless

- Stage action either goes beyond, or contradicts, the words spoken by the characters

- The characters talk (use language) to fill the emptiness between them, using clichés, slogans or jargon, which distorts or parodies conventional speech

- Humans are seen to inhabit a universe but are out of step with it. The meaning of existence is unclear and their place within it is without purpose. They are bewildered, troubled and obscurely threatened

- Plays aim to startle the viewer, challenging the idea that life is comfortable or conventional

- What happens on stage (the action) has little to do with what the characters say to one another

- The hidden, implied meaning of words is more important than what is actually being said

- Scenic effects and staging are abstract and often ‘borrowed’ from popular theatre arts such as mime, ballet, acrobatics, conjuring and music-hall clowning.

Absurdist writers and works

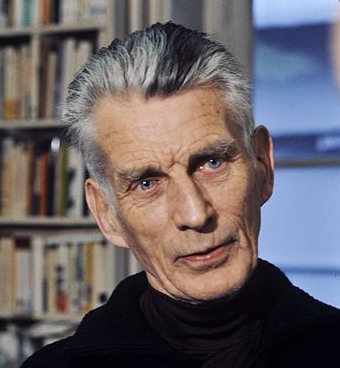

Samuel Beckett (1906-1989) was an Irish writer and novelist who spent much of his adult life in Paris. Beckett’s work is marked by lack of movement or plot. Many of Beckett’s plays, such as Waiting for Godot (1953), Endgame (1957), Krapp's Last Tape (1958) and Happy Days (1961) examine the pointlessness of life itself. His battered characters often occupy barren landscapes where they struggle to make sense of their lives but many of Beckett’s plays also contain great humour within the bleakest of settings. Waiting for Godot (1953) is the story of two tramps waiting for a man called Godot whom they don’t know. The stage is entirely bare except for a tree and a mound. The dialogue is as sparse as the set and achieves a poetic truthfulness. The first performance was a total disaster, but probably no single play had more influence on British drama in the twentieth century.

Samuel Beckett (1906-1989) was an Irish writer and novelist who spent much of his adult life in Paris. Beckett’s work is marked by lack of movement or plot. Many of Beckett’s plays, such as Waiting for Godot (1953), Endgame (1957), Krapp's Last Tape (1958) and Happy Days (1961) examine the pointlessness of life itself. His battered characters often occupy barren landscapes where they struggle to make sense of their lives but many of Beckett’s plays also contain great humour within the bleakest of settings. Waiting for Godot (1953) is the story of two tramps waiting for a man called Godot whom they don’t know. The stage is entirely bare except for a tree and a mound. The dialogue is as sparse as the set and achieves a poetic truthfulness. The first performance was a total disaster, but probably no single play had more influence on British drama in the twentieth century.

Eugene Ionesco (1909-1994) was born in Romania, lived in Paris and wrote work that challenged theatrical conventions. A common theme of Ionesco’s plays, such as The Bald Soprano (1950), The Chairs (1952) and Rhinoceros (1960), is the inability of man to communicate with man. His plays feature bizarre themes, such the inhabitants of a small, provincial French town who turn into rhinoceroses.

Eugene Ionesco (1909-1994) was born in Romania, lived in Paris and wrote work that challenged theatrical conventions. A common theme of Ionesco’s plays, such as The Bald Soprano (1950), The Chairs (1952) and Rhinoceros (1960), is the inability of man to communicate with man. His plays feature bizarre themes, such the inhabitants of a small, provincial French town who turn into rhinoceroses.

Jean Genet (1910-1986) was a criminal and was imprisoned many times in his youth. A great admirer of Antonin Artaud, Genet wrote about social issues and subject matter often considered too controversial in his time, in plays such as The Thief’s Journal (1949), Deathwatch (1954), The Balcony (1956) and The Screens (1961). Jean Paul Sartre (1905-1980) valued Genet’s work so much that he petitioned the government to release Genet from prison.

Theatrical tensions and transitions – post war drama

From Absurdism to kitchen-sink

Background and context

The latter half of the twentieth century was a time of increased political and social tension, not only in Britain but across the whole of Europe and the Western world:

- The so-called Cold War between the United States and Soviet Russia and their respective allies began in 1947 and was to last until 1991. There was no large-scale fighting directly between the two sides, although there were conflicts in Korea, Vietnam and Afghanistan that both sides (and their allies) supported

- Nuclear weapons, held by both sides, posed a serious threat to the security of the planet and in Britain the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) (also called the ‘Ban the Bomb’ movement) organised protests and marches

- In Europe, the Suez Crisis (1956) caused unrest in the Middle East when Britain and France failed to keep control of the Suez Canal

- Britain was no longer a great power and could only stand by and watch as Russian troops crushed the Hungarian uprising of 1956 and thereafter oversaw control of the country.

Socially there was disruption of another kind in Britain as Rock and roll arrived from America during the 1950s. Meanwhile, the working classes became more articulate and the ‘angry young man’ began to make a significant mark on the theatre of the time.

The ‘new wave’ playwrights

A post-war generation authors and playwrights referred to as the ‘angry young men’ came to prominence in the 1950s, reflecting the tensions in British society. As the playwright and critic Bernard Kops wrote in 1956:

We write about the problems of the world today because we live in the world of today. We write about the young because we are young. We write about Council flats and the H-bomb and racial discrimination because these things concern us and concern the young people of our country, so that if and when they come to the theatre, they will see that it is not divorced from reality, that it is for them and they will feel at home.

John Osborne

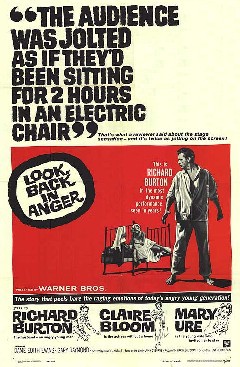

John Osborne (1929-1995) is credited with being the inventor of the new style of British theatre that came to be called ‘kitchen sink drama’; plays that were set in everyday working class life and dealt with the anger felt by people whose lives were controlled by those in power.

John Osborne (1929-1995) is credited with being the inventor of the new style of British theatre that came to be called ‘kitchen sink drama’; plays that were set in everyday working class life and dealt with the anger felt by people whose lives were controlled by those in power.

The central character of Osborne’s play, Look Back in Anger (1956), is a working class man called Jimmy Porter, who believes that his life and relationships are failures because of the failing society in which he lives:

There aren’t any good, brave causes left. If the big bang does come and we all get killed off it won’t be in aid of the old fashioned grand design. It’ll just be for the Brave New-nothing-very-much-thank-you. About as pointless and inglorious as stepping in front of a bus.

Osborne Porter wrote a number of plays which were performed at the Royal Court and the National Theatre, such as The Entertainer (1957), as well as later work for television, but his first play is still regarded as his greatest work.

Harold Pinter

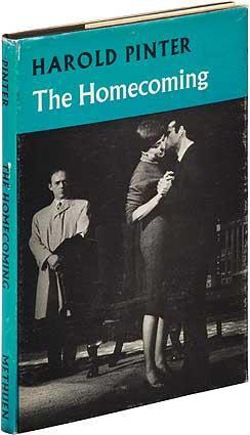

Harold Pinter (1930-2008) described the meaning of his plays as being ‘the weasel beneath the cocktail cabinet’. Many of his plays use a small cast of everyday characters and day-to-day events which become metaphors for the hopelessness of existence.

Harold Pinter (1930-2008) described the meaning of his plays as being ‘the weasel beneath the cocktail cabinet’. Many of his plays use a small cast of everyday characters and day-to-day events which become metaphors for the hopelessness of existence.

His early work, such as The Birthday Party (1958), The Caretaker (1960), The Dumb Waiter (1960) and The Homecoming (1965) fitted both the absurdist and kitchen-sink styles of drama, but all his plays have an underlying sense of menace and are often very disturbing. Theatre critic Harold Hobson wrote of his work:

Pinter is the inventor of a device called the ‘Pinter Pause’, where actors use a deliberate silence to build tension in a scene. Pinter also wrote radio drama and screenplays for the cinema, being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2005.

Arnold Wesker

Many of Arnold Wesker’s plays are semi-autobiographical and are set in London’s East End, where Wesker (b. 1932) was brought up. As well as The Kitchen (1957) and Chips with Everything (1962), Wesker wrote The Roots Trilogy: Chicken Soup with Barley (1958); Roots (1959); I’m Talking About Jerusalem (1960). This recounts the political history of Britain from 1936 to 1960 through the eyes of a Jewish working class family in the East End of London. Although Wesker continues to write plays, the first five of his plays are regarded as his most significant.

Many of Arnold Wesker’s plays are semi-autobiographical and are set in London’s East End, where Wesker (b. 1932) was brought up. As well as The Kitchen (1957) and Chips with Everything (1962), Wesker wrote The Roots Trilogy: Chicken Soup with Barley (1958); Roots (1959); I’m Talking About Jerusalem (1960). This recounts the political history of Britain from 1936 to 1960 through the eyes of a Jewish working class family in the East End of London. Although Wesker continues to write plays, the first five of his plays are regarded as his most significant.

Joe Orton

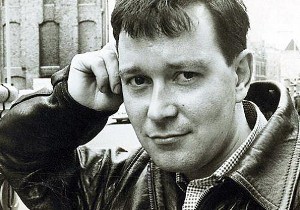

The career of Joe Orton (1933 -1967) was short, lasting from 1964 until his death. After an unsuccessful acting career, he began to write in the late 1950s, encouraged by his lover and partner Kenneth Halliwell. Orton’s black comedies shocked, outraged and amused audiences. The adjective ‘Ortonesque’ is sometimes used to refer to similar styles of work.

The career of Joe Orton (1933 -1967) was short, lasting from 1964 until his death. After an unsuccessful acting career, he began to write in the late 1950s, encouraged by his lover and partner Kenneth Halliwell. Orton’s black comedies shocked, outraged and amused audiences. The adjective ‘Ortonesque’ is sometimes used to refer to similar styles of work.

Orton’s three full-length plays, Entertaining Mr. Sloane (1964), Loot (1965), and What the Butler Saw (produced posthumously in 1969), were outrageous black comedies about moral corruption, violence, and sexual greed. He also wrote four one-act plays during these years, including Funeral Games (1968). All of Orton’s plays present situations where the innocent suffer and the guilty thrive; the forces of order are corrupt whilst violence and cruelty are never far from the surface. Harold Pinter’s eulogy at Orton’s funeral, concluded: ‘He was a bloody marvellous writer.’

Theatre in the sixties and beyond

Background and context

Protest, politics and pop culture

The end of the 1960s was a watershed; a time of violent change with protests (mainly carried out by young people) against the Vietnam War, Communist oppression and authoritarian governments. It was also the time of the so-called ‘sexual revolution’ when women took control of their sexual lives and the feminist movement gathered force. Fashion reflected the new freedoms with the mini skirt and ethnic clothes, whilst long hair was worn as a mark of dissent.

The end of censorship

1968 saw the end of censorship in the theatre, which allowed topics like religion, politics and sex to be freely discussed. In 1967, the British Parliament’s adoption of the Sexual Offences Act, which decriminalised homosexual acts in England and Wales, meant that homosexuality could be acknowledged and nudity on stage became legal. As soon as the censorship law was repealed, two significant musical shows, Hair (1968) and Oh! Calcutta! (1970), took advantage of the new stage freedom with notorious scenes of full frontal nudity.

Collaborative creativity

Improvisation and work shopping became the working method of many theatre companies and the 1970s saw the growth of small fringe or collaborative companies:

- Joint Stock (1974-1989) was founded in London by David Hare, Max Stafford-Clark and David Aukin. Its aim was to present new plays by using workshops for writers to gather material, which then inspired the writing of new plays. These were then rehearsed and produced by the company. This is sometimes referred to as the ‘Joint Stock Method’

- General Will Theatre Company (early 1970s) was co-founded by David Edgar (b. 1948) in Bradford. It specialised in a plays that were political commentaries, using the techniques of music hall and burlesque for comic effect. General Will came to a halt when the only gay member of the company took exception to the heterosexual slant of the material and went on strike in mid-performance

- Portable Theatre Company (early 1970s), founded by playwright David Hare, was dedicated to performing ‘short, nasty little plays’ that were politically significant. It was in this troupe that Hare wrote his first play, because someone had failed to deliver a script to be performed. Hare went on to become a significant political playwright whose works continue to shock and challenge modern audiences.

Later twentieth century plays and playwrights

Edward Bond

Bond (b 1934) describes himself as a writer of ‘Rational Theatre’, which he sees as an opposition to the theatre of the absurd. For Bond, theatre is a means of analysing society. His plays do not address the individual situations of characters, but are works that examine the world in terms of how society is dominated by capitalism. Bond is one of the most revolutionary political playwrights of the twentieth century. His plays are shocking and intended to make the audience leave the theatre with a sense of need for urgent social action.

Bond said of his work:

He calls his dramatic method ‘the Aggro technique’ and his work has much in common with that of Bertolt Brecht. In Bond’s play Saved (1965) a baby in a pram is stoned to death by a group of young men. The play was initially banned, receiving its first public performance in Britain only after the abolition of censorship in 1968. Bond wrote:

Sir David Hare

David Hare (b. 1947)’s play, Via Dolorosa (1998), dramatises conversations he had with Palestinians and Israelis during a visit to the Middle East. Hare’s work, like that of David Edgar, originates from agit-prop theatre. His plays also address the state of the nation, reporting the reality of current political issues through the voices of those (characters) involved, such as his trilogy of plays about major British institutions Racing Demon (1990), Murmuring Judges (1991) and The Absence of War (1993).

David Edgar

Edgar (b 1948) began writing as a journalist and his plays reflect his own desire to be ‘a secretary for the times through which I am living’. (picture) Like many of his contemporaries, Edgar’s work is also political and his subject matter is often taken from actual social and political events. Destiny (1976) tells the story of a by-election campaign in the West Midlands and the rise of right-wing extremism in Britain during the mid-1970s. The Shape of the Table (1990) and Playing with Fire (2005) deal with political machinations in Europe and Britain.

Tom Stoppard

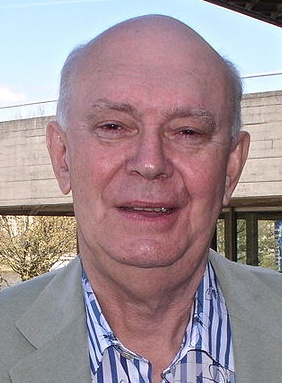

Sir Tom Stoppard (b. 1937) is a Czech-born British playwright who has produced work for theatre, television, radio and the cinema. Stage plays include Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1967), Travesties (1974), Arcadia (1993) and The Coast of Utopia (2002). He also co-wrote the screenplays for Brazil and Shakespeare in Love.

Sir Tom Stoppard (b. 1937) is a Czech-born British playwright who has produced work for theatre, television, radio and the cinema. Stage plays include Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1967), Travesties (1974), Arcadia (1993) and The Coast of Utopia (2002). He also co-wrote the screenplays for Brazil and Shakespeare in Love.

Stoppard’s theatre work takes its inspiration from literary and philosophical sources and is therefore very different from other writers of his generation, although his early plays do show elements of absurdism. Stoppard's plays have been described as ‘plays of ideas’, that examine philosophical concepts and make them entertaining through clever use of wordplay and jokes. He has been a key playwright of the National Theatre and is one of the most internationally performed dramatists of his generation.

Alan Ayckbourn

Ayckbourn’s characters are familiar and comically human, their language commonplace and each play focuses on the theme of some kind of moral choice. Major successes include: The Norman Conquests trilogy (1973), Absurd Person Singular (1975), Bedroom Farce (1975), Just Between Ourselves (1976), A Chorus of Disapproval (1984), Woman in Mind (1985), A Small Family Business (1987), Man Of The Moment (1988), House & Garden (1999), Private Fears in Public Places (2004).

Twentieth century women playwrights and practitioners

The Female Voice

Writing in 1999, playwright David Edgar acknowledged a ‘third wave of new playwrights … who emerged in the early to mid-1980s’. They were women, writing plays about women. Females had performed on stage for centuries, but until the latter part of the twentieth century, there had been very few women playwrights or practitioners. However, the development of the feminist movement saw things begin to change as women began to make a significant contribution to the theatrical world.

Introduction to Monstrous Regiment (1991) by Gillian Hanna

Joan Littlewood

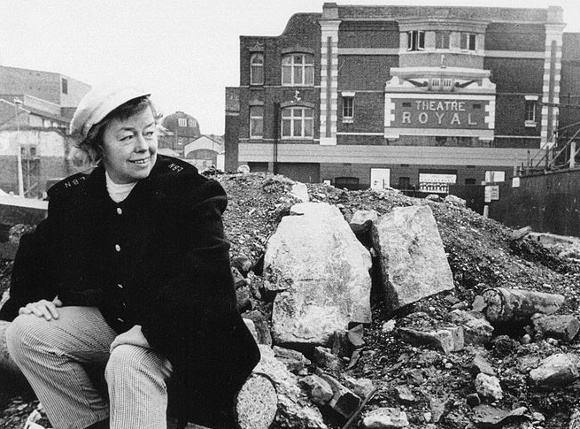

Joan Littlewood (1914-2002) was one of the most influential British theatrical directors of the twentieth century, mounting experimental productions of plays for working-class audiences that dealt with social issues. In 1945, Littlewood founded a company in Manchester called Theatre Workshop, which moved to the Theatre Royal, Stratford, in the East End of London in 1953.

Joan Littlewood (1914-2002) was one of the most influential British theatrical directors of the twentieth century, mounting experimental productions of plays for working-class audiences that dealt with social issues. In 1945, Littlewood founded a company in Manchester called Theatre Workshop, which moved to the Theatre Royal, Stratford, in the East End of London in 1953.

Influenced by the work of Bertolt Brecht, Littlewood encouraged audience participation during performances; allowed actors to improvise on stage and used techniques originally developed in the music hall. Productions became collective, with the actors sharing in planning and devising them. Oh! What a Lovely War (1963) was a devised piece using Brechtian techniques such as projected newspaper headlines; direct address; popular songs of the period and other devices to criticise the Great War of 1914-18. Other notable productions were The Quare Fellow (1956) and The Hostage (1958) by Brendan Behan, A Taste of Honey (1958) by Shelagh Delaney and Fings Ain't Wot They Used T'be (1959) a play by Frank Norman with original music and lyrics by Lionel Bart

Radical feminist theatre of the 1970s and beyond

Feminist theatre of a radical kind came from groups such as The Women’s Theatre Group (1973) and Monstrous Regiment (1975). The aims of the latter were to:

- Produce great shows

- Discover and encourage women writers

- Explore a theory of feminist culture, asking ‘what is a feminist play?’

- Resurrect women’s ‘hidden history’

- Give women opportunities for work – especially in technical areas which had always been male preserves

- Put real women on the stage with no more stereotypes.

Caryl Churchill

The plays of Caryl Churchill (b. 1938), who was a founder member of Joint Stock and Monstrous Regiment theatre companies, link feminism with a socialist view on society. Her works ask questions rather than coming to conclusions and vary widely in terms of dramatic technique, using song, verse drama, dance and overlapping dialogue. Her best known plays include:

- Top Girls (1982), in first act of which, Marlene, the managing director of the Top Girls agency, throws a dinner party for famous or mythical women from past history. The second act reveals the other side of Marlene’s story; an abandoned daughter and an estranged sister are the price Marlene has paid for her choice to pursue a successful career

- In A Light Shining in Buckinghamshire (1976) Churchill uses the English Civil War to examine whether or not radical changes in society are ever possible to achieve

- In Cloud Nine (1979) the sexes are cross-cast, with men playing female roles and vice versa to examine possible different sexual relationships in the days of the British Empire.

Pam Gems

The plays of Pam Gems (b. 1925) put women at the centre of the action, showing the pressures and the social consequences of the changing sense of women’s roles; sexual and family patterns. Her plays are not as political as those of other feminist playwrights, concentrating more on humane examinations of the roles that women play in a man’s world.

Like Churchill, Gems often turns to historical figures in plays such as Queen Christina (1977); Piaf (1978) and The Blue Angel (1991) which all use successful women as their subjects and show how they can rise above troubled backgrounds and achieve success because of their own resilience and determination.

Timberlake Wertenbaker

Born in America and brought up in France, Timberlake Wertenbaker (b. 1955) is now regarded as a major British playwright and has strong connections with the Royal Court Theatre, for which she was writer-in-residence from 1984-85. (picture) She has written original work for the Royal Shakespeare Company; translated and adapted novels and Greek legends for the stage and translated works by Classical Greek and French authors.

Wertenbaker is concerned not so much with specific feminist ideology as the universal injustices that result from oppression and brutality. In her most famous play Our Country’s Good (1988) she explores:

The play is set in 1897 and is an account, based on historical evidence, of the transportation of a group of convicts to Australia. The convicts rehearse and perform the Restoration play The Recruiting Officer (1706) by George Farquhar and their experience of the language of the theatre liberates and transforms every character.

Sarah Kane

Scholars of the work of Sarah Kane (1971-1999) identify elements of expressionist theatre and Jacobean tragedy in her plays and critics have named her style as ‘In-Yer-Face theatre’. Kane’s plays, such as Blasted (1995), Phaedra´s Love (1996), Skin (1997), Cleansed (1998), Crave (1998) and 4.48 Psychosis (produced posthumously in 2000) shocked audiences with brutal and powerful images of rape and torture (both physical and emotional) and themes of redemptive love, sexual desire, pain and death. Kane’s first play, Blasted used the viewpoints of both oppressor and victim to reflect the horror of the Bosnian conflict, whilst she said of Cleansed:

almost every line in Cleansed has more than one meaning ... I wanted to stretch the theatrical language.

Drama in the twentieth century: conclusions

Two themes seem to stand out with regard to twentieth century drama:

Theatre for all

The century witnessed a growing sense that theatre was not intended to serve as an exclusive form of entertainment for the upper classes, but was a democratic theatre for all classes. This was certainly evident not only in Britain, but throughout Europe and the United States, where the work of practitioners such as Brecht, Stanislavsky and Lee Strasberg created ways of performing that revolutionised not only the theatre but also television and the cinema.

Female dramatists

The emergence of women as significant contributors to the development of theatre has been most significant in Britain and the United States. The goal of feminist theatre has not been about women in the theatre as much as the role of women in society. Female directors, scenic designers, and composers did not become common until the last decades of the century, yet the voice of women has been heard on stage for over one hundred years. The concept of ‘plays by women and about women’ is not new, but it remains central to the feminist movement.