Rhys, Jean Contents

Jean Rhys' final years

Jean Rhys' final years

Publication

Wide Sargasso Sea was published in October 1966 when Jean Rhys was 76 years old. Some of the first reviewers of the novel thought it was too gothic and melodramatic. Perhaps they had forgotten its connections to Jane Eyre! However, the novel was given serious critical attention and great praise in influential literary magazines in Britain and the United States.

Literary reputation

Jean Rhys’ reputation grew steadily into the 1970’s:

- There were articles in academic journals by well-known writers and critics, including A. Alvarez. His opinion that she was ‘the best living English novelist’ was very influential in securing her place in contemporary literature

- All her writings received renewed attention. Her early novels were republished, some in paperback. They were also translated into other languages and adapted for film and TV

- These developments brought Jean Rhys to the attention of a wider, more popular audience. They were also intrigued by the life story of this ‘strange, shy, very dignified lady’ as the journalist Hunter Davies described her

- The content of her novels and stories, their focus on the experience of women, caught the attention of the growing feminist movement. This also extended her readership and, eventually, helped to ensure her inclusion in programmes of study in schools, colleges and universities.

Personal improvements

Jean Rhys’ personal situation improved to some extent in these final years of her life, although she still suffered from depression and she could be difficult for her friends to deal with. At last, she attained financial security. Money came in from the sales of her books as well as various prizes, grants and awards. She was awarded a Civil List pension in 1974 and, for her services to literature, a CBE in 1978.

She was also much less lonely and isolated. The acclaim for her writing ensured that she was reconnected with the literary world. She made new friends including Sonia Orwell (George Orwell’s widow) and Antonia Fraser, the writer and historian. They, and several others, helped to look after Jean Rhys as she grew more frail in her old age.

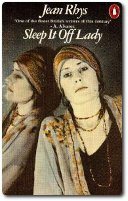

They also helped her to edit and publish short stories written at this time. Her final collection, Sleep It Off, Lady was published in 1976.

Decline

Jean Rhys worked on her writing right up until her death. In the last three years of her life, she was increasingly housebound by illness and frailty. However, she was still writing and redrafting her stories and working on an autobiography. This was never completed but the fragments were collected into Smile Please, published after her death.

Jean Rhys died in May 1979 after a fall and a series of strokes.

The problem of autobiography and Jean Rhys’ writing

Reflections of life?

Most readers are interested in connections between the life and work of a writer. But writers vary in the degree and nature of that connection.

Jean Rhys presents her readers with a body of work that seems to be thoroughly autobiographical. Right from the beginning her stories and novels came out of her own experiences of childhood, of men, of being alone. As many critics have observed, her first four novels can be seen as variations of the same themes and their heroines the same woman, a version of Rhys at different stages in her life.

Jean Rhys also used writing as a form of therapy. Diana Athill, her editor, said that her novels and stories were a way of ‘purging unhappiness’, of writing out the bad things that happened to her.

In one of her notebooks, she wrote that she had attempted to be an effective ‘channel’. This remark draws attention to the intuitive process of writing, to her sense that she was moved by internal creative forces which could control her, rather than she rationally controlling them.

The shaping of fiction

The danger with a writer like Rhys is that readers forget the imaginative and formal aspects of her work and read the stories as if they were fact. Jean Rhys didn’t have a lot of interest in fact; she was much more concerned with the transformative power of fiction and with issues of language, voice and structure.

Rhys was a very conscious writer, capable of enormous attention to detail and to the shape and organisation of her material. This last was particularly important, so that any details that didn’t work within the overall structure of the writing would be ruthlessly pruned or reshaped to fit. If that meant that they no longer fitted the ‘facts’ as others saw them, then she could justify the alterations as serving a higher aesthetic purpose.

Another reason why it would be unwise to rely on Rhys’ writings as factually accurate about her life (or anyone else’s) is that she produced most of her autobiographical writing late in life. Her memories of Dominica, her relationships, her response to English culture, had already been authored as fiction many years before. As an old lady in her 70s and 80s, the boundaries between memory and story had long been broken down.