The Great Gatsby Contents

Moral collapse

‘Modern’ social behaviour

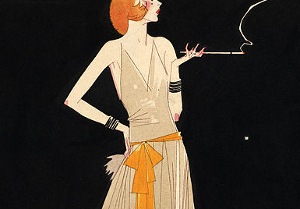

There are certainly many challenges to conventional morality in the novel, with the female characters in particular embracing their new-found freedom to drink, smoke, drive and attend wild parties. These depictions of Flapper-like behaviour would have been repugnant to many contemporary readers, and the implied references to sexual activity would have been unacceptable for some. Drunkenness, to which all the characters except Gatsby and Jordan succumb, was also a serious concern in the 1920s, with those in support of Prohibition holding passionate views about the evils of alcohol.

There are certainly many challenges to conventional morality in the novel, with the female characters in particular embracing their new-found freedom to drink, smoke, drive and attend wild parties. These depictions of Flapper-like behaviour would have been repugnant to many contemporary readers, and the implied references to sexual activity would have been unacceptable for some. Drunkenness, to which all the characters except Gatsby and Jordan succumb, was also a serious concern in the 1920s, with those in support of Prohibition holding passionate views about the evils of alcohol.

Disconnected youth

Essentially, the novel is concerned with the experiences of young people, and has no reference to the accepted structures of society such as the nuclear family or the workplace hierarchy. Daisy and Tom have a daughter, but she is mentioned three times, seen once, and occupies an extremely minor place in the story. Meanwhile, Daisy, Gatsby and Tom almost dismantle this family unit completely by their actions.

Older members of society, who might exert a moral and conservative influence, are largely absent from the text. Henry Gatz is a ‘solemn old man’ who only appears at the end, and seems somewhat naïve in his awe of his son’s life and achievements. Wolfsheim, aged fifty like the ‘pioneer debauchee’ Dan Cody, is a criminal who can hardly be expected to uphold morality in any credible way. Nevertheless, he does have a family (glimpsed briefly) and he seems to have a moral code:

Lack of social cohesion

Ideas such as friendship are explored indirectly in this novel, with Nick becoming Gatsby’s main friend and advocate. However, loyalty is a rare quality, as demonstrated by the small number of mourners present at Gatsby’s funeral. Jordan remains loyal to her ‘girlhood’ friend Daisy, as Catherine is loyal to her sister Myrtle, but beyond these examples, there is a real lack of social cohesion since friendships are often shallow and artificial. At Gatsby’s party, Nick sarcastically observes:

Nick is keenly aware that there is very little virtuous behaviour in the world of the novel, and seems to yearn for the restoration of morality:

Nick himself is not innocent, although he is quite confusing in his admission of guilt. He claims to be the ‘one of the few honest people I have ever known’, but later undermines this by accepting Jordan’s accusation that he is a ‘bad driver’ (a phrase which he and Jordan imbue with the meaning of ‘careless’ in terms of relationships).

Dishonesty

Dishonesty is seen in many forms:

- It is identified as Jordan’s key fault

- It is regarded by Nick as being a typical female trait

- Gatsby and Wolfsheim are shown to lead major criminal activities

- Gatsby’s statements about his origins are quickly exposed as false

- Daisy’s insincerity is a form of dishonesty and many of her statements are to be understood as ‘sophisticated’ or cynical, thinly veiling her dissatisfaction with life: ‘I’m p-paralysed with happiness.’

Infidelity

Another form of dishonesty and disloyalty is infidelity, which pervades the novel. Almost every couple is affected by this. In Chapter 1 we learn that Tom has ‘got some woman in New York’ and find out later that he is a serial womaniser. Myrtle, Daisy and Gatsby are similarly guilty, while Nick and Jordan assist in reuniting Gatsby with Daisy, so become tainted with the same guilt. Fidelity, in any case, is not rewarded in the novel. George Wilson merely suffers humiliation, resorts to violence and is responsible for his own and Myrtle’s destruction, while failing to identify or punish the true culprit.

Avarice

Possibly at the root of all the immorality in The Great Gatsby is the love of money and material goods, thereby echoing the New Testament precept from 1 Timothy 6:10:

Fitzgerald depicts the Jazz Age society as being driven by materialism. Among the inhabitants of East Egg and West Egg, excessive wealth is exhibited in terms of houses, cars, clothing and other luxury possessions. Gatsby’s parties are a lavish display of wealth, prioritising personal pleasure to the exclusion of all else, and establishing the status of those who have leisure time to indulge in these activities.

Much of the infidelity in the novel is prompted by a love of money:

- Myrtle is exploiting Tom’s desire in order to gain money and material goods

- Gatsby is infatuated with Daisy at least in part because of her wealth (‘her voice is full of money’)

- Daisy is seduced by Gatsby’s display of wealth, notably his expensive shirts.

Carelessness

Jordan and Nick’s conversation about carelessness is also important in establishing the moral values of the novel. Nick initially criticises her for being a ‘rotten driver’ and this conversation develops into a discussion of ‘careless people’. Ironically, Jordan says she hates careless people, even though she is one herself.

The definition shifts to include people who are ‘careless’ in relationships, perhaps not caring or loving. In Chapter 9, Jordan complains that Nick too was ‘careless’, which led to her suffering from his ill-treatment in the relationship. Jordan is essentially self-preoccupied, but Nick uses the term more broadly. He reflects that Daisy and Tom had no sense of social responsibility or respect for others. Selfishness is deplored at this point, and Nick is also dismissive of other selfish characters, such as Klipspringer and even Wolfsheim, who place self-preservation above social forms.

Death and judgement

Gatsby’s funeral stands as an important contrast to the hedonism and superficiality facilitated by wealth. It is only attended by loyal family and friends, namely Henry Gatz, Nick and Owl Eyes, as well as servants and the postman, and there is no display of wealth, merely a focus on the rain and the ground. The funeral scene may serve as a kind of ‘memento mori’ motif, developing the imagery of death associated with the ‘valley of ashes’ to remind the reader that wealth cannot protect anyone from death, and can even lead to death in some circumstances.

The three deaths in the novel certainly imply the collapse of some sort of moral universe. There is no sense that society has been purged by the loss of these characters, or that appropriate justice will claim the perpetrators. At the same time, Nick’s own sense of loss regarding Gatsby also suggests a suspension of appropriate moral judgement. Right from the beginning of the novel Nick has exempted him, and ultimately he even exalts him morally, reiterating that Gatsby’s ‘extraordinary gift for hope … [and] romantic readiness’ are not qualities he ‘shall ever find again’.

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

Recently Viewed

-

The Great Gatsby » Moral collapse

just now