Articles

- Drama developments

- Mystery and morality plays

- The earliest permanent theatres

- Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre design

- Female roles before 1660

- Restoration theatre

- Commedia dell’Arte

- Eighteenth century theatre

- Nineteenth century melodrama

- Naturalism and realism

- Twentieth century experiments

- Later twentieth century theatre

- Literary features of Elizabethan drama

Twentieth century experiments

Background and context

An important thing to remember is that theatrical forms evolve and change but do not do so in neat time periods. New styles of theatre do not automatically wipe out the forms that existed prior to their appearance, neither do they often exist independently of one another.

Realism and naturalism did have a very significant impact on the theatre of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but that did not mean that the forms that had developed in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries disappeared overnight. The fact is that the old and the new styles of making plays existed side by side and often blended into one another.

For example, the concept of the ‘well made play’, which originated in France, stubbornly refused to disappear when the realists and naturalists swept in to change the face of theatre. It spread throughout Europe and still exists in mainstream theatre, cinema and television.

The well-made play

Structured entertainment

The concept of the well-made play (in French, pièce bien faite) was invented by French writer Eugene Scribe (1791 -1861) and dominated the stages of Europe and America for most of the nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth century. Scribe believed that audiences went to the theatre to be entertained, not to be instructed or improved, so he used a very simple five point formula to construct his plays:

- Exposition – gives the background information that is needed to understand the story; introduces the protagonist (main character); the antagonist (opposing character); the basic conflict (what sets the characters against one another) and the setting (where the action takes place)

- Complication and development – obstacles or events that create tension as the story unfolds (sometimes called ‘rising action’)

- Crisis – a high point of tension that follows a complication (sometimes called a ‘climax’) After a climax there would be a decrease in tension (sometimes called ‘falling action’). The rest of the play would repeat rising action – climax - falling action until the end.

- Dénouement – at the end of the play, literally the ‘unravelling’ or the ‘un-knotting’ when all is made clear to the audience

- Resolution – the final conclusion when all is resolved and brought to an end (sometimes called the ‘curtain scene’).

Plotting and suspense

Well-made plays called for complex and highly artificial plotting; a build-up of suspense; a climactic scene in which all problems are resolved; and a happy ending. Romantic conflict was a staple subject, for example a pretty girl being forced to choose whether to marry a poor but honest young man or a wealthy, unscrupulous villain. Suspense was created by misunderstandings between characters, mistaken identities, secret information, lost or stolen documents, and similar devices. The formula also worked well for a comic style called farce which used absurd situations, improbable plots with many twists and turns and physical humour to entertain the audience.

The scène à faire and the coup de theâtre

All the above elements were arranged into Acts and scenes which varied in number, dividing the play neatly into sections. The concept of the well-made play was to maintain the action in a series of ‘curves’ (rising and falling actions) that built towards a scène à faire - literally a scene that had to be done at that point. It would also contain a coup de theâtre, an event that transformed the dramatic situation. The idea was to keep the audience on the edge of the seat and, in order to intensify the excitement, the curtain was often brought down at the moment of climax. The structure worked equally well with serious subjects and comedy.

Critics, supporters and the legacy of the well-made play

Critics such as Émile Zola and George Bernard Shaw denounced Scribe’s work and that of his successor, Victorien Sardou, for concentrating more on the formula than the characters or content, but their opinions had little effect. Scribe and his assistants wrote hundreds of plays and libretti that were translated, adapted, and imitated all over Europe.

Although Shaw mocked the dramaturgy of the well-made play, calling it ‘sardoodledom’, he used some of its features in his Plays Pleasant and Unpleasant and some aspects of the well-made play structure also featured in the work of Shaw’s contemporary Henrick Ibsen, who directed a number of Scribe's plays in Norway before producing his own dramatic works. Ibsen’s early plays clearly drew on the style, while later works introduced elements of symbolism.

- English novelist and playwright Wilkie Collins, whose novel The Woman in White was dramatised and produced at the Olympic theatre in October 1871, summed up the well-made play formula as follows:

'Make 'em laugh; make 'em week; make 'em wait.' - Arthur Pinero used the form effectively for his play The Second Mrs Tanqueray (1893)

- In France, Émile Augier and Alexandre Dumas (fils) used the techniques in serious plays dealing with social conditions such as prostitution and the emancipation of women

- Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Ernest (1895) used melodramatic structures as well as features of the well-made play to examine some of the favourite themes of his time: loyalty, sacrifice, undying love, manners, and social respectability

- The techniques and principles of the well-made play were also used to create significant works by twentieth century writers such as Lillian Hellman, Terence Rattigan and Noel Coward.

Conclusion

The well-made play exerted a very significant influence on the history of theatre and can be seen to have shaped the form of drama in a variety of movements that were to develop in the twentieth century, including realism, naturalism, and symbolism. It has continued to survive up to the present day, not only in contemporary plays but most significantly in television dramas and soap operas.

The age of the ‘–ism’

Although the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are best remembered for the birth of modern realism and naturalism, other important movements developed at the same time.

For the purpose of this article, we have tried to categorise the various abstract forms of theatre that came into being in the early part of the twentieth century. It is important to remember that, as with all categories of the arts, the different forms do not exist in isolation, but blend into one another. Elements of more than one form can and do appear in the work of many practitioners. They are presented here in no specific order of appearance or importance.

Symbolism in the theatre (1885-1910)

A symbol is a way of representing something other than what it is at face value and is a basic feature in most art; artists commonly employ language and representations of objects, both real and imagined, as signs of something else. A symbol is intended to suggest some idea or an emotion in the mind of the person looking at it, but the object also has a real existence. For example, a dove is a bird (its ‘real’ or ‘concrete’ form) but a dove can also be a symbol of gentleness, peace or the Holy Spirit(in its ‘symbolic’ form).

In the theatre, symbolism can be achieved by means of lighting, set design, colour, movement, costume and props. Many of the sets and props in symbolist plays were used to represent social values or emotions. For example:

- A huge throne could symbolise power

- A window could symbolise freedom

- A machine could represent oppression.

The symbolist movement began in the late nineteenth century with the work of a group of French poets. It soon spread to the visual arts and theatre, reaching its peak between 1885 and 1910. It was the first significant rejection of naturalism / realism and created the avant-garde in modern theatre, through alternative styles of acting and production.

A condensed symbolism check list

Playwrights and directors were influenced by the psychological research of the time such as Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams (1900). This work examined the idea that, in dreams, the mind and spirit occupy a space beyond the physical world, where symbols have great significance. Thus, in the theatre:

- Literal realism was replaced by elements of mysticism and spirituality

- Plays focused on the revelation and depiction of characters’ inner lives

- Plays had unconventional plot lines (or sometimes no plot line at all)

- Production techniques used symbols, metaphor, poetry, music and ‘symbolic’ lighting.

Some symbolist writers

Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949)

Maeterlinck believed that theatre was ‘a shadow, a reflection, a projection of symbolic forms’. His play The Blind (1890) had a cast of anonymous characters who communicated mainly by groans or gasps on a stage set dominated by a gallows and a hanging corpse, symbolising death. The play is said to have influenced Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot (1953).

Vsevelod Emilievich Meyerhold (1874-1940)

Meyerhold was an original member of the Moscow Arts Theatre and studied with Nemirovich-Danchenko and Stanislavsky until 1902, when he left to become a director himself. He believed that the director was the primary theatre artist and used techniques of Commedia dell'Arte, vaudeville and circus in his work.

Meyerhold’s work is interesting because it was influenced by Stanislavsky’s system, but also had elements that would later be seen in the Epic Theatre style developed in Germany by Bertolt Brecht.

Signature features of Meyerhold's symbolism

- Performances were often given in ‘found spaces’; not theatres, but factories or streets

- The ‘fourth wall’ was often broken in performance, with direct acknowledgement of the audience

- House lights were left on

- The apron stage was extended into the audience

- Actors were positioned in the house (in the audience)

- Performances used multi-media devices such as projection, signs and music

- Theatrical devices were fully visible, making the audience aware that they were watching a play

- Actors were physically trained in Meyerhold’s acting theory of ‘biomechanics’ or ‘physical theatre’

- Stage sets were constructed to resemble machines on which the actors performed.

Expressionism

A movement across the arts

Expressionism is a term usually used in connection with early twentieth century art, but it was never a single school with a particular leader and a number of different artists painted in the style. The movement was most influential in Northern Europe, particularly in Germany and its influence was seen not only in painting, but also in architecture, literature, dance, film, music and theatre.

The overall aim of the expressionist artists was to reject the idea that art was a mirror of reality. Instead, the artist should confront the darkest aspects of reality through nightmarish visions of the world, distorting it to create an emotional effect that evoked moods and ideas.

Vasilly Kandinsky (1866-1944); Edvard Munch (1863-1944) and Paul Klee (1879-1940) were among the major expressionist painters. Expressionism in film began with Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) and Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1926).

Expressionism in the theatre

Some signature features of the form

- Rebellion against propriety, common sense, conformity and convention

- Rejection of the conventions of the well-made play and stage realism

- Bizarre events

- Disjointed plots

- Poetic and/or obscene language

- Themes closely associated with humanitarian causes such as pacifism and progressive social reforms

- Stage images symbolising mental states

- Highly subjective dramatic action, frequently distorted and dreamlike and often seen through the eyes of the protagonist

- Themes that are often opposed to the norms of society and family

- Incidents that are random, not always logical or related

- Characters are often representative types with titles instead of names.

Writers and practitioners

Benjamin Franklin Wedekind (1864-1918)

Benjamin Franklin Wedekind (1864-1918)

- Spring Awakening (1891) was (and remains) a very controversial work. The subject matter of sexuality, rape, child abuse, suicide and abortion meant that the play could not be staged until 1906. Long monologues, similar to stream of consciousness writing, revealed the inner thoughts and feelings of characters in a style very popular within German Expressionism

- The Lulu Plays: Earth Spirit (1895) and Pandora's Box (1904) tell the story of a young dancer who sleeps with a succession of men to rise in society, but later falls into poverty and prostitution. The plays’ themes of sex, lesbianism and violence (including an encounter with Jack the Ripper) were controversial and shocking for the time, although the character of Lulu has subsequently achieved cult status.

Expressionism had a strong impact on a number of very different dramatists, including Bertolt Brecht, Eugene O'Neill, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Max Frisch and many others. From the 1960s, Political Theatre rediscovered elements of expressionism and, in the 1980s, theatre design borrowed from it heavily.

Surrealism

Origins

Surrealism

The Surrealist movement spanned the years between the two World Wars in Europe (1916-1939). It developed from the ‘anti art’ theories of Dadaism.

More on Dadaism:

Dada was never a movement as such, but a loose collection of very angry artists who found themselves in exile in neutral Switzerland during the Great War of 1914-18.

They were so disgusted with a society that had allowed the ‘war to end all wars’ to happen, that they protested by declaring themselves non-artists and their art as non-art. Ironically, they created some of the most interesting art of the period.

Dadaist art was art that was meant to shock. It could and did use any kind of object or subject – the more senseless, the better – to make the point that art had become meaningless in a world that had allowed such a horror as the Great War to happen. Marcel Duchamp for example, painted a moustache on the Mona Lisa; scribbled an obscenity underneath and displayed a urinal as a sculpture entitled Fountain

André Breton, the French poet and critic who published The Surrealist Manifesto (1924) defined the movement as one that aimed to join conscious and unconscious experience so as to create ‘an absolute reality, a surreality.’

Surrealism (that which is dream-like or ‘real-but-not-real’) drew heavily on the theories of Sigmund Freud, whereby the unconscious mind fed the imagination. Breton defined genius as being able to access this source of artistic creativity.

Surrealism in the theatre

Alfred Jarry (1873-1907)

French poet and playwright Alfred Jarrry was one of the founders of the avant-garde and his work had a major influence on the development of the surrealist and absurdist movements in the theatre, although this did not come about until after his death in 1907.

Jarry’s key work was a trilogy of three plays:

- Ubu Roi: King Ubu (1896)

- Ubu Cocu: Ubu Cuckolded (1897)

- Ubu Enchaînê: Ubu Enchained (1899).

The plays were parodies of some of Shakespeare’s tragedies and the Oedipus Rex (Oedipus the King) trilogy by the classical Greek tragedian, Sophocles. The plays were staged using puppets, placards and masks, whilst the acting style used elements of pantomime and burlesque. Jarry created the central character, King Ubu, as a grotesque metaphor for the modern man.

Antonin Artaud (1896-1948)

Antonin Artaud was a French actor, writer, director and producer. He was a member of the avant-garde surrealist movement and a friend of its founder, André Breton, until Artaud left the movement in 1926 when Breton gave the surrealists’ support to Communism.

Antonin Artaud was a French actor, writer, director and producer. He was a member of the avant-garde surrealist movement and a friend of its founder, André Breton, until Artaud left the movement in 1926 when Breton gave the surrealists’ support to Communism.

Inspiration

Alfred Jarry and Jarry’s alter-ego character Ubu were inspirational to Artaud and, after breaking with the surrealist movement, Artaud co-founded the Théâtre Alfred Jarry, with Raymond Aron and Roger Vitrac. In addition, visits abroad to Japan, Bali and Mexico enabled Artaud to study very different styles of performance, including ceremonial rituals. He also became interested in Jewish, Hindu and Middle Eastern cultures.

The Theatre of Cruelty

Artaud wrote a number of manifestos to explain his thoughts about what theatre should be. His Manifeste du théâtre de la cruauté (1932; Manifesto of the Theatre of Cruelty) and Le Théâtre et son double (1938; The Theatre and Its Double) outlined his ideas:

- Actor and audience should share or exchange intimate thoughts and feelings, especially on a mental or spiritual level

- Gestures, sounds, unusual scenery and lighting should all combine to form a language that was superior to spoken words

- ‘Cruelty’ meant that the audience's senses should be constantly disturbed in order that the spectator would be shocked into seeing the rotten state of his world

- Theatre should be life-changing, in the same way as an outbreak of plague

- Text was the greatest enemy of freedom on stage

- The audience should be so changed and challenged by a performance that watching it would have a serious physical effect - literally a ‘gut-wrenching’ experience

- Theatre should put mankind in contact with its primitive self

- Theatre should not be a literary experience, but a dangerously challenging sensory event.

Artaud’s own stage works were failures and he was diagnosed as incurably insane in 1938, but he became a cult figure and a major influence on the Absurdist theatre of Jean Genet, Eugène Ionesco, Samuel Beckett and many other European dramatists.

Epic Theatre

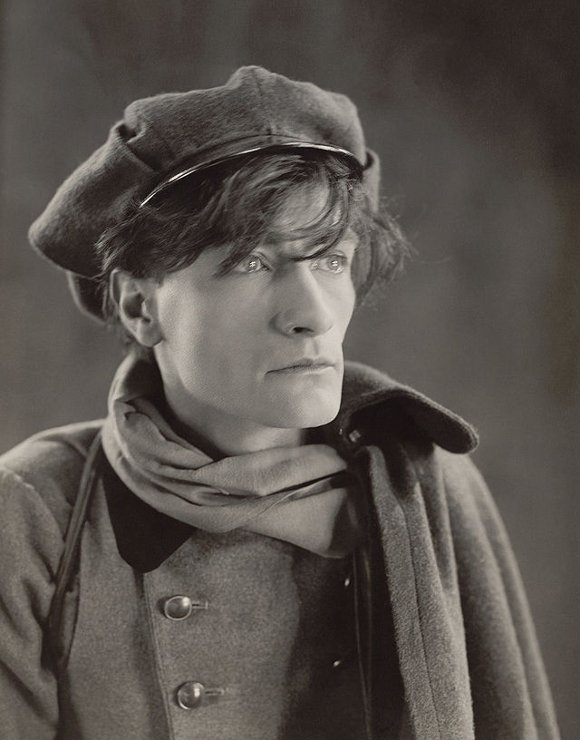

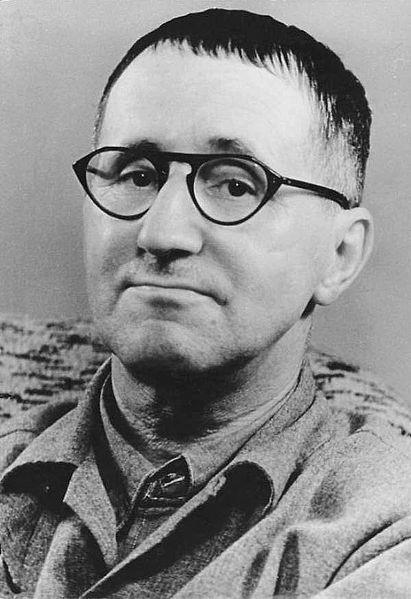

Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956)

Brecht’s early work could be described as Expressionist until the mid-1920s, at which time he began to develop a unique form of theatre that made him one of the most celebrated stage practitioners of modern times.

Brecht’s early work could be described as Expressionist until the mid-1920s, at which time he began to develop a unique form of theatre that made him one of the most celebrated stage practitioners of modern times.

Epic Theatre was intended to change the world through theatrical performance that helped audiences to become more critically aware. Brecht criticised traditional theatre which for him was based on the Aristotelian principle of catharsis. Brecht saw this as a form of passive consumption; he claimed that he did not want to entertain people, but to make them think. In his opinion, an audience watching a play should not hang up their brains with their hats when they entered the theatre.

Brecht objected to theatre presenting events as reality because that left no opportunity for plays to make political or social comments, so he created something radical by changing the rules of theatre completely.

The rules of Epic Theatre in brief

- Plays were episodic in structure, often dealing with history or foreign lands

- Action covered long periods of time and happened in many different places

- Plots were intricate, involving many characters

- The goal of any play (and the theatre in general) was to instruct

- Plays used the Verfremdungseffekt: a German phrase which means literally ‘to make strange’, also sometimes called ‘the alienation technique’. Brecht believed that the audience should be ‘distanced’ so they would interact with theatre intellectually rather than emotionally

- Plays often used a narrator to comment directly to the audience on what was happening

- Actors would speak about their character and actions in the third person

- The audience always aware that they were in a theatre. Lights were bright; stage mechanics were visible; sets were very basic; no ‘box sets’ were used

- Plays often used past events to comment on the present (for example, Mother Courage and her Children (1939) is set during the Thirty Years War, but is obviously about Germany in the 1930's before the outbreak of the Second World War)

- Music, back projection, signs and banners were used to explain and inform

- Actors would deliberately break the ‘fourth wall’ and address the audience directly.

Some of the notable plays

- The Threepenny Opera (1928) was adapted from John Gay’s ‘The Beggar’s Opera’ with an original score by composer Kurt Weill. It mocked the sentimental musical and was a great success. One of the signature songs, Mack the Knife, became an international hit

- Mother Courage and her Children (1939) is possibly Brecht’s most famous play. It is an anti-war play, written in 1939 after Germany invaded Poland, and first performed in 1941

- The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui (1941), a parable play about Hitler's rise to power, set in pre-war Chicago.

- The Caucasian Chalk Circle (1943) was derived from an original Chinese play Circle of Chalk by Li Xingdao and adapted by Brecht from his own short story. The drama used the device of a ‘play within a play’ as a parable about a peasant girl who steals a baby but becomes a better mother than its natural parents.

Brecht’s political position

As a lifelong socialist and supporter of the political views of Karl Marx, it was inevitable that the rise of Hitler’s fascist regime in Germany in the 1930s would place Brecht in a difficult position. In 1933 he left Germany and lived in Denmark, Sweden and the Soviet Union before settling in the United States. In Germany his books were burned and his citizenship was withdrawn, but in exile he worked with the Hollywood film industry and wrote most of his great plays.

In 1947 the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began an investigation into the entertainment industry in order to discover and prosecute people who held left-wing views. Brecht was accused of being a Communist but denied the accusation. Soon after giving evidence he left America and returned to East Germany, where he founded the Berliner Ensemble which became the country's most famous theatre company.

Together with those of Konstantin Stanislavsky, Bertolt Brecht’s performance theories and ideas about the nature of theatre live on in much of the drama of the present day.