The Handmaid's Tale Contents

- Interpretation and the opening epigraphs

- Section 1: Night - Chapter one

- Section 2: Shopping - Chapter two

- Section 2: Shopping - Chapter three

- Section 2: Shopping - Chapter four

- Section 2: Shopping - Chapter five

- Section 2: Shopping - Chapter six

- Section 3: Night - Chapter seven

- Section 4: Waiting room - Chapter eight

- Section 4: Waiting room - Chapter nine

- Section 4: Waiting room - Chapter ten

- Section 4: Waiting room - Chapter eleven

- Section 4: Waiting room - Chapter twelve

- Section 5: Nap - Chapter thirteen

- Section 6: Household - Chapter fourteen

- Section 6: Household - Chapter fifteen

- Section 6: Household - Chapter sixteen

- Section 6: Household - Chapter seventeen

- Section 7: Night - Chapter eighteen

- Section 8: Birth Day - Chapter nineteen

- Section 8: Birth Day - Chapter twenty

- Section 8: Birth Day - Chapter twenty-one

- Section 8: Birth Day - Chapter twenty-two

- Section 8: Birth Day - Chapter twenty-three

- Section 9: Night - Chapter twenty-four

- Section 10: Soul scrolls - Chapter twenty-five

- Section 10: Soul scrolls - Chapter twenty-six

- Section 10: Soul scrolls - Chapter twenty-seven

- Section 10: Soul scrolls - Chapter twenty-eight

- Section 10: Soul scrolls - Chapter twenty-nine

- Section 11: Night - Chapter thirty

- Section 12: Jezebel's - Chapter thirty-one

- Section 12: Jezebel's - Chapter thirty-two

- Section 12: Jezebel's - Chapter thirty-three

- Section 12: Jezebel's - Chapter thirty-four

- Section 12: Jezebel's - Chapter thirty-five

- Section 12: Jezebel's - Chapter thirty-six

- Section 12: Jezebel's - Chapter thirty-seven

- Section 12: Jezebel's - Chapter thirty-eight

- Section 12: Jezebel's - Chapter thirty-nine

- Section 13: Night - Chapter forty

- Section 14: Salvaging - Chapter forty-one

- Section 14: Salvaging - Chapter forty-two

- Section 14: Salvaging - Chapter forty-three

- Section 14: Salvaging - Chapter forty-four

- Section 14: Salvaging - Chapter forty-five

- Section 15: Night - Chapter forty-six

- Historical notes

- Human relationships in The Handmaid's Tale

- Mothers and children in The Handmaid's Tale

- Individualism and identity in The Handmaid's Tale

- Doubling in The Handmaid's Tale

- Gender significance and feminism in The Handmaid's Tale

- Power in The Handmaid's Tale

- Survival in The Handmaid's Tale

- Hypocrisy in The Handmaid's Tale

- Myth and fairy tale in The Handmaid's Tale

- Structure and methods of narration

Feminism and The Handmaid's Tale

The Feminist Movement

Atwood is well known for her feminist views and The Handmaid's Tale raises many questions about the role, status and treatment of women in the modern world.

Atwood is well known for her feminist views and The Handmaid's Tale raises many questions about the role, status and treatment of women in the modern world.

The feminist struggle, even in recent times, has a longer history than might be imagined:

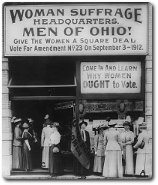

- In the USA, the first National Women's Rights Convention was held in Massachusetts in 1850

- The National Women's Suffrage Association, campaigning for votes for women, was formed in 1869

Various States in America gradually gave women the vote - In Britain, the National Society for Women's Suffrage was founded in 1872

- In England, many, but not all, women over the age of 30 were given the vote in 1918 at the end of the First World War.

However, votes were only one aspect of feminist aspirations. Equality of education, pay and status in society were others; there is still a heated debate in Britain over the relatively small number of women Members of Parliament. In many other countries there is no pretence even that women have equal status with men.

The status of women in The Handmaid's Tale

Atwood raises feminist issues immediately by depicting Gilead as a régime in which men have all the power. Women are subservient in every way and are unable to work or even to have bank accounts of their own. Atwood also extends the debate further by making Offred's mother a feminist who takes part in protests and demonstrations. In chapter 20, for example, Offred recalls seeing, at the Red Centre, a film about a feminist demonstration in which her mother was taking part. Atwood is probably thinking of such real-life events as the 1974 march in San Francisco by Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media.

In contrast, Atwood creates Serena Joy who, we learn in chapter 8, used to make televised speeches about ‘how women should stay at home' - yet ironically, of course, these speeches were made by a woman who had a flourishing independent career on television; in Gilead, such a career is now unthinkable.

No simple answers

The issues are complex. For example, Offred does not appreciate all her mother's activities. ‘I didn't want to live my life on her terms,' she tells us at the end of chapter 20. In chapter 28 she recalls that she:

It is not only Offred who does not feel the same passion about the status and treatment of women. Moira is working, we are told in chapter 28, for a women's collective who ‘put out books on birth control and rape' but ‘there wasn't as much demand for those things as there used to be.'

Luke and Offred, too, seem to feel that they live in a period which has moved beyond the need for active feminism. Luke sees himself as egalitarian and enjoys teasing Offred's mother, ‘pretending to be macho' by saying that ‘women were incapable of abstract thought.' Yet once Offred's job and bank account have been taken away, she feels immediately (chapter 28) that there has been a shift in their relationship:

She wonders if, in fact, Luke likes the greater power he has, now that:

Moira is a figure from Offred's generation who rejects the feminine role society suggests for her. Yet she warns Offred (in chapter 28) that she is over-optimistic in thinking that the battle of the feminist movement has already been won. Offred has sneered at her for thinking that she could

‘create Utopia by shutting herself up in a women-only enclave'

because ‘Men were not just going to go away'. Moira's reply is that this is no reason for living with them, because:

However, by the end of chapter 39, when we see what has become of Moira in Jezebel's, it does seem as if Moira's suspicions about male-dominated society were well-founded. The ‘women's culture' which Offred's mother so wanted has become in Gilead, as Offred tartly remarks in chapter 21, a very different matter:

The perspective of the Historic Notes

Atwood does not allow the situation, or the debate, to rest there. When we come to the final section, the Historical Notes, we see that women are able to hold their own with men in academic circles. The Chair (not ‘Chairwoman') of the conference is a female Professor. Even then, however, Atwood leaves us with the feeling that the feminist battle still has some way to go, as Professor Pieixoto clearly feels it appropriate to make sexist jokes - jokes which arouse ‘Laughter, applause' from the audience.