The Pardoner's Prologue and Tale Contents

- Social / political context

- Religious / philosophical context

- Literary context

- l.1-40: The link between The Physician's Tale and The Pardoner's Prologue

- The Pardoner's Prologue - l.41-100

- The Pardoner's Prologue - l.101-138

- The Pardoner's Prologue - l.139-174

- The Pardoner's Tale - l.175-194

- The Pardoner's Tale - l.195-209

- The Pardoner's Tale l.210-300: Gluttony and drunkenness

- The Pardoner's Tale l.301-372: Gambling and swearing

- The Pardoner's Tale l.373-422: The rioters hear of death

- The Pardoner's Tale l.423-479: The rioters meet an Old Man

- The Pardoner's Tale l.480-517: Money

- The Pardoner's Tale - l.518-562: Two conspiracies

- The Pardoner's Tale - l.563-606: Love of money leads to death

- The Pardoner's Tale l.607-630: Concluding the sermon

- The Pardoner's Tale l.631-657: Selling relics and pardons

- Final link passage l.658-680: Anger and reconciliation

Death in society and culture

Population growth and decline

In 1300 there may have been as many as six million people in England. Instead of an economy primarily based on agricultural production from estates, trade was becoming more important. Producers of both food and other commodities were becoming more likely to diversify or specialise, producing for the market and not just for personal and local consumption. English wool and cloth were major exports.

However, the population growth of the thirteenth century was followed early in the fourteenth century by:

- A series of bad harvests

- Recurrent periods of poor weather

- Outbreaks of disease among cattle as well as humans.

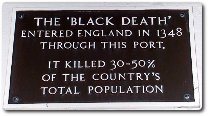

The famines which resulted led to a decline in population, and this was exacerbated in 1348-9 by the Europe-wide plague known as the Black Death.

What was the Black Death?

Black Death is a modern term. Fourteenth-century people talked about the ‘pestilence' or even ‘the Death' for this European pandemic of the years 1348-9. Historians in the past believed that it was bubonic plague, which was spread by rats. However, this epidemic is now believed by many scientists to have involved perhaps more than one disease, the most virulent of which was probably a virus. The black rat was, in fact, very rare in medieval England.

Black Death is a modern term. Fourteenth-century people talked about the ‘pestilence' or even ‘the Death' for this European pandemic of the years 1348-9. Historians in the past believed that it was bubonic plague, which was spread by rats. However, this epidemic is now believed by many scientists to have involved perhaps more than one disease, the most virulent of which was probably a virus. The black rat was, in fact, very rare in medieval England.

Whatever the causes, this highly infectious disease swept westwards through Europe and killed many. It spread through Britain from the south coast and is estimated to have killed at least a third of England's population.

The social effects of the Black Death

For the remainder of the fourteenth century, the population was lower (perhaps at around three million even at the end of the century). This meant that for many people:

- Wages became higher – employers desperate for workers had to pay more to attract them

- The costs of many foodstuffs fell – with fewer people to buy goods, those wishing to sell had to cut prices.

The results of the Black Death and this demographic change were bad for upper-class estate-owners:

- Their lands were yielding less than they had in their fathers' and grandfathers' times

- Costs, including wages, were rising.

For people lower down the socio-economic scale, however, the post-plague world held some opportunities:

- There was an increase in mobility, as workers moved from their villages and towns to take up paid work

- There was a decrease in the use of ‘unfree' serf or bonded labour in favour of wage-earners.

There were several further outbreaks of plague in later fourteenth-century England. These often affected the young especially, making population recovery slow for over a century.

The intellectual impact of the Black Death

It has to be said that, despite what some modern commentators say, there is surprisingly little direct reference to the effects of the emotional or cultural and social effects of the Black Death. The reality of living through a plague doubtless helped to emphasise what was already a major theme in European medieval art and in religious teaching. Death was frequently represented, through art, literature and religious practices. It was believed to be both sensible and spiritually beneficial to face up to the fact that death awaits all. In the light of that, views had to be adjusted:

- About worldly pleasures and success

- About the importance of the soul and of the things of eternity.

Memento mori

Much medieval art bluntly depicts the unappealing realities of death and the body's decay, to shock the onlooker into accepting that the fate of the soul is far more important than any aspect of life in this world. Such art and literature, and the attitude it conveys is often summed up in the Latin phrase ‘memento mori', meaning ‘Remember you must die'.

For more on the philosophical impact of death, see Religious / philosophical context > Death and mutability

Life expectancy in medieval England

Apart from the plague as a cause of mass death, the chances of living to old age were much lower than they are today. Life expectancy in Chaucer's time may have averaged around 30-35 years, but that meant a large number of babies and toddlers died. It does not mean everyone died in their 30s! Once people had survived infancy, their chances of living into, say, their 50s or 60s could be quite good. A women's life expectancy increased greatly when and if they had survived their dangerous years of childbearing. Strong and fortunate people might survive into their 60s, 70s, even beyond.

However, sudden and unexpected deaths were common. Many men and women died young owing to the lack of:

- Effective medicines

- Proper sanitation

- Safe and successful surgery

- Adequate scientific understanding of disease and the body.

These normal dangers surrounding medieval people made acceptance of one's own mortality a sensible outlook. It was believed that sudden death, before a person had confessed his or her sins and obtained absolution from a priest, could jeopardise a believer's place in heaven in the after-life.

Youth, middle age and old age

According to medieval perceptions:

- Youth was often said to last from 10 to 20, more often 30. There was a general image of youth as a time of cheerfulness, love and foolishness

- Middle age lasted from then to 50 or 60

- Old age was the period thereafter. Old age was marked by greater seriousness and less energetic activities. It was also the period in life when it was natural to concentrate as much as possible on the soul and spiritual devotions.