Tess of the d'Urbervilles Contents

- Social / political context

- Religious / philosophical context

- Chapters 1-9

- Chapters 10-19

- Chapters 20-29

- Chapters 30-39

- Chapters 40-49

- Chapters 50-59

- Tess as a 'Pure Woman'

- Tess as a secular pilgrim

- Tess as a victim

- The world of women

- Tess as an outsider

- Coincidence, destiny and fate

- Disempowerment of the working class

- Heredity and inheritance

- Laws of nature vs. laws of society

- Modernity

- Nature as sympathetic or indifferent

- Patterns of the past

- Sexual predation

- Inner conflicts: body against soul

Patterns of the past

The significance of the past

The role of past history is one of the most significant themes of Tess of the d'Urbervilles. Most of Hardy's novels include a discussion of the past in some form or another, but nowhere is this done as insistently as in Tess. From Pastor Tringham's revelation of family ancestry in the first chapter to the pagan past of the penultimate chapter, Hardy examines the impact of the past on Tess's life. On the whole, this impact is destructive and a major component of her personal tragedy.

Hardy presents history through three different perspectives.

The prehistoric past of Tess

The prehistoric past is first mentioned in Ch 4, with its mention of Bulbarrow 'engirdled by its earthen trenches':

- These trenches are part of an Iron Age hill fort

- Other references to this range of hills running through the centre of the county also mention prehistoric features: tumuli and barrows, chalk figures, flints etc.

- Hardy later reinforces this idea of ancient time with Tess's consciousness of the cosmos and:

- At the end of the book, prehistoric time re-emerges with references to the Ancient Britons on Egdon Heath just outside Sandbourne and their trackways (Ch 55)

- In Ch 58, the action centres around Stonehenge, seen as the centre of ancient sun-worship.

In between, Hardy describes the ancient woodland of The Chase (Ch 5, 11) with its 'Druidical mistletoe':

- Symbolically, mistletoe signs death (the myth of Balder in Norse mythology), and to the druids, human sacrifice

- This becomes a sign of Tess's eventual sacrificial death

- In classical mythology, woods were places of mischief and disorder (see Wild woods)

- This ancient woodland is to be distinguished from the New Forest, which belongs to the second band of time.

Ancestral time

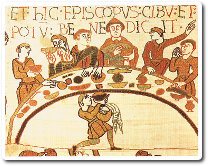

This is the most frequently quoted layer of the past, stretching from the Medieval period to the eighteenth century. It is the period of the original d'Urbervilles and other Norman families who inherited great tracts of land from William the Conqueror. Gradually, many of these families declined and even became extinct in their title-bearing and land-owning lines. Only minor branches of the family survived in very lowly circumstances (Ch 19, 54).

This is the most frequently quoted layer of the past, stretching from the Medieval period to the eighteenth century. It is the period of the original d'Urbervilles and other Norman families who inherited great tracts of land from William the Conqueror. Gradually, many of these families declined and even became extinct in their title-bearing and land-owning lines. Only minor branches of the family survived in very lowly circumstances (Ch 19, 54).

This layer of time is perhaps the most destructive for Tess. It is associated with:

- Loss and decline: 'How are the Mighty Fallen', as Jack Durbeyfield has inscribed on his unpaid for tombstone (Ch 1, 54). Jack's pathetic efforts to restore family fortunes are laughable and embarrass Tess. All they materially have left are a spoon and a graven seal!

- Death, especially at the family burial place at Kingsbere. The family finally has nothing left but this tomb to call their own (Ch 52)

- Revenge /punishment: Hardy makes a point of suggesting the evil done to Tess is much the same as the evil inflicted by her lawless ancestors on maidens in the past (Ch 11, 47, 50). This is one pattern of history that suggests some sort of moral balance, even though inflicted on innocent generations. At one point Hardy mentions the biblical subtext of the consequences of sin being outworked on the third and fourth generations, even if they do not share the original guilt

- Doom. When Angel and Tess spend their wedding night in a d'Urberville house the past directly impinges on the present. The portraits of the two women from the past prevent Angel at one point from relenting (Ch 52, 53). He can see only their cruelty. The legend of the d'Urberville coach, in which a murder was committed, adds to the sense of doom and foreboding (Ch 33, 51).

Recent history

The past of living memory is referenced through:

- Country traditions, such as the Club-walking, which are part and parcel of everyday life, yet which are constantly being modified and even falling into disuse

- A constantly changing landscape (see Geographical symbolism). For example, Hardy reminds us that Talbothays has been formed out of several other farms, whose contours are no longer visible (Ch 17). The implication is that the landscape is continually in flux

- Social and economic changes. The most obvious is the legal arrangements for Jack's retaining the cottage in Marlott. He is the third generation of 'liviers'. After his death, the house reverts to the landlord, who can turn them out as he wishes.

Escaping the past

Tess's great battle is to escape the past. For her this is:

- Primarily, the immediate past of Alec's incursion into her life

- To a lesser extent, the ancestral responsibility laid on her by her father.

However, the message of the novel seems to be that escape is impossible. It is best to turn and fight. Tess endeavours to do this by her confession of the past to Angel. Yet it is a fight she loses, as she tells her story too late.

Hardy deliberately manipulates the plot to keep bringing the past back (see Coincidence, destiny and fate). Thus:

- Alec keeps being mentioned or reappearing (Ch 26, 27, 44)

- The man from Trantridge keeps reappearing as a witness and reminder (Ch 33, 41, 43)

- The Darch girls reappear briefly at Flintcombe-Ash (Ch 43)

- Stories remind her of the past, especially Jack Dollop's (Ch 21)

Tess's final heroic effort to escape the past is actually to try to kill it, in the form of Alec. Ironically this pushes her further back into the past, firstly the ancestral past as she walks through the medieval New Forest, then the archaeological past, as she reaches Stonehenge.

Hardy seems to be saying that ideally Tess desires to live in the present, which is neither the past nor modernity. Such a desire is strongly seen during her engagement, when she wishes they could remain engaged for ever. However, Hardy does not grant such bliss to his mortal lovers. The future always holds the threat of the repetition of the past, the decline of love and growth of disillusionment (Ch 31).