Articles

- Impact of classical literature

- The cultural influence of classical ideas

- Literary allusions to classical literature

The Golden age

Happier times

When we talk of a ‘Golden Age' of Brazilian football or a ‘Golden Age' of English drama, we are employing an extremely ancient concept. However, we use the phrase much more lightly, less literally than the ancients did: they believed there had been a distinct age in which the world as a whole had been much better.

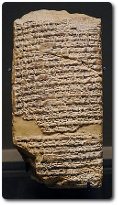

Signs of a longing for a better past can be seen in some of the earliest human writing. The first known works of literature, the writings of the Sumerians, who lived in what is now Iraq in the third millennium BCE, are full of references to a former age, from which  the present time could only be seen as a falling-off:

the present time could only be seen as a falling-off:

- The Epic of Gilgamesh describes a world in which heroes had more courage and more strength

- The ‘Sumerian King List' (about 1800 BCE) looks back wistfully to the times of great kings who reigned for thousands of years at a stretch

- In addition, the great Hindu epic, the Mahabharata, thought to have been composed around 1000 BCE, harked back to a ‘Perfect Age' when the world was new and everything was good.

Measured out in metals

The ancient Greek idea of the Golden Age of human perfection is first recorded in the work of the poet Hesiod, who was writing in about the eighth century BCE. It was a time, he said, when men and women lived ‘like gods': they did not have to work to support themselves, because a benevolent nature supplied them with all their needs:

- The trees gave them fruit at every time of year

- The crops sprang up from the earth untended

- The weather was always warm and sunny

- Since all had everything they needed, there was no call for greed or envy

- Quarrelling and war were completely unknown.

It goes without saying that this was not the age in which Hesiod and his contemporaries felt they lived. The ideal Golden Age had ended at some vague time in the distant past, giving way to a ‘Silver Age', a ‘Bronze Age', then the race of heroes (half gods like Hercules, who approached the 'golden' race). However, things had got worse since then, wrote Hesiod. His was an ‘Iron Age' in which people had to break their backs with work to feed and clothe themselves and in which war, injustice and nastiness were rife.

More on different Iron ages: Hesiod's ‘Iron Age' should not be confused with that of the modern archaeologists. They too describe human development in terms of metals, according to the skills different societies had attained. Making bronze from a mixture of copper and tin was comparatively easy: ‘Stone Age' cultures had gained the necessary skills from about 3000 BCE. The ‘Bronze Age' went on until the (much harder) techniques involved in working iron had been mastered: this happened from about 1200 BCE. Iron is much harder, more durable and more adaptable than bronze, so from the archaeologists' point of view, the coming of the ‘Iron Age' marked an advance.

Paradise before a fall

The world of Hesiod's Golden Age closely resembles that of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, as recounted in the first book of the Bible, Genesis. They were expelled from their earthly paradise because the devil (in the guise of a speaking serpent) tempted them to aspire to god-like status, leading them into disobedience against God.

The Greek tradition has some similarities. Although the mythology is muddled, with conflicting versions of the story, there is general agreement that it was after the overthrow of Cronos, King of the Titans, by his son Zeus that the mythical Greek Iron Age began.

The role of Prometheus

The onset of the 'Iron Age' is also linked to when Prometheus gave the secret of fire to humanity:

- Prometheus was a Titan, one of the race of gods who had reigned in heaven through the Golden Age, but were toppled from power by Zeus and his Olympians (so called because they were said to live on Mount Olympus, in northern Greece)

- Zeus was the god of the sky, and his weapon was the thunderbolt: his lightning-bolts gave him the power to create fire wherever he pleased

- To get back at Zeus, Prometheus is said to have stolen fire from him and shown human beings how to create and use it for themselves

- Zeus punished Prometheus severely, shackling him to a rock on a mountain crag: an eagle came each day to tear out and eat his liver; each night it grew back, ready for the next day's assault.

More on Prometheus: Fire was an invaluable gift: it allowed humanity to move forward, allowing forests to be cleared for agriculture, and the arts of metalworking to be developed. Given the importance of his contribution to technological progress – and what he suffered to help bring that about – Prometheus has been associated ever since with heroic daring and originality in the cause of science. Today we use the word ‘Promethean' for a scientist or scientific venture which seems especially intrepid in its ambition.

Degeneration and hope

The myth of the Golden Age implies the progressive degeneration of the human race. However, according to Hesiod, the race of heroes did not all die out; some survived on the Isles of the Blest, which contained the garden of the Hesperides (which had trees bearing golden fruit) or, according to Homer, on the Elysian Fields, both these mythical places being 'in the west'.

Gradually, Elysium was seen as the reward for right living heroes after death (i.e. the classical equivalent of the Christian heaven); it was the destination of Aeneas, where he was reunited with his dead father and witnessed the Blest dancing and singing. Whether 'in the west' or in the afterlife, the physical and moral perfection of these destinations was seen as a return to the original Golden Age.

Other cultural references

Book of Genesis

The Creation; Fall of humankind and universal or original sin; Noah and the Flood; the call of Abraham (start of salvation history), followed by the stories of the other patriarchs, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph.

Big ideas: Creation; Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve; Cain and Abel; Noah and the Flood; Patriarchs

Famous stories from the Bible: Adam and Eve / Creation; Noah's Ark; Abraham

The Creation; Fall of humankind and universal or original sin; Noah and the Flood; the call of Abraham (start of salvation history), followed by the stories of the other patriarchs, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph.

Big ideas: Creation; Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve; Cain and Abel; Noah and the Flood; Patriarchs

Famous stories from the Bible: Adam and Eve / Creation; Noah's Ark; Abraham