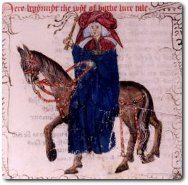

The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale Contents

- The Prologue: introductory comments

- Part one: l.1 'Experience' - l.76 'Cacche whoso may'

- Part two: l.77 'But this word' - l.134 'To purge uryne'

- Part three: l.135 'But if I seye noght' - l.162 ' Al this sentence'

- Part four: l.163 'Up sterte' - l.192 'For myn entente'

- Part five: l.193 'Now sires' - l.234 'Of hir assent'

- Part six: l.235 'Sire old kanyard' - l.307 'I wol hym noght'

- Part seven: l.308 'But tel me this' - l.378 'This know they'

- Part eight: l.379 'Lordinges, right thus' - l.452 'Now wol I speken'

- Part nine: l.453 'My forthe housebonde' - l.502 'He is now in the grave'

- Part ten: l.503 'Now of my fifthe housebond' - l.542 'Had told to me'

- Part eleven: l.543 'And so bifel' - l.584 'As wel of this'

- Part twelve: l.585 'But now, sire' - l.626 'How poore'

- Part thirteen: l.627 'What sholde I seye' - l.665 'I nolde noght'

- Part fourteen: l.666 'Now wol I seye' - l.710 'That women kan'

- Part fifteen: l.711 'But now to purpos' - l.771 'Somme han kem'

- Part sixteen: l.772 'He spak moore' - l.828 'Now wol I seye'

- Part seventeen: The after words l.829 'The frere lough' - l.856 'Yis dame, quod'

- The Wife of Bath's Tale: Introductory comments

- Part eighteen: l.857 'In the' olde days' - l.898 'To chese weither'

- Part nineteen: l.899 'The queen thanketh' - l.949 'But that tale is nat'

- Part twenty: l.952 'Pardee, we wommen' - l.1004 'These olde folk'

- Part twenty-one: l.1005 'My leve mooder' - l.1072 'And taketh his olde wyf'

- Part twenty-two: l.1073 'Now wolden som men' - l.1105 'Ye, certeinly'

- Part twenty-three: l.1106 'Now sire, quod she' - l.1176 'To lyven vertuously'

- Part twenty-four: l.1177 'And ther as ye' - l.1218 'I shal fulfille'he Holocaust and the creation of

- Part twenty-five: l.1219 'Chese now' - l.1264 'God sende hem'

- Reaction to the Wife's Tale

- Themes in The Wife of Bath's Tale

- The struggle for power in The Wife of Bath's Prologue

- The 'wo' that is in marriage

- The portrayal of gender in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Desire and The Wife of Bath's Tale

- Is there justice in The Wife of Bath's Tale

- Social criticism in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Marriage and sexuality in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Mastery in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Debate, dispute and resolution in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Tale and teller in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

The Wife of Bath within her Prologue

First person narration

For discussion of Chaucer's account of the Wife of Bath in his General Prologue to The Canterbury Tales see Narrative > The portrait of the Wife of Bath in The General Prologue)

In the Wife's Prologue Chaucer reveals her character through the first person narration of a gossip. She offers a bold account of her struggle for dominance over her husbands and the views of women that they preach from ‘authoritative' texts. Chaucer cleverly uses this first person narration so that we are drawn to make our own judgements of the Wife.

Appearance

In first person narration, it can be difficult to create an opportunity to show the reader / listener what a character looks like. (Various devices are used to overcome this problem in some texts, e.g. the narrator might look at herself in a mirror or other reflective surface, or her face and appearance may be decoded by another character whose speech she reports.)

In first person narration, it can be difficult to create an opportunity to show the reader / listener what a character looks like. (Various devices are used to overcome this problem in some texts, e.g. the narrator might look at herself in a mirror or other reflective surface, or her face and appearance may be decoded by another character whose speech she reports.)

Chaucer gives a lively, impressionistic portrait of the Wife in The General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales from l.445 where she is described by Chaucer's pilgrim narrator. See Appearance as a sign > looking at the Wife of Bath.

If you have read Chaucer's The General Prologue you will have a visual image of the Wife as a large, dominating, fair, red-faced woman dressed in expensive cloth.

The Wife's explanation of her behaviour

First person narrators can, however, easily be given views to deliver about their own character or personality. It does not seem awkward for a narrator to embark on ‘What kind of person I am'. In The Wife of Bath's Prologue Chaucer creates a forceful narrative voice. The Wife's unrelenting self-advertisement reveals this gossiping voice to be sexually experienced and dominating.

The influence of astrology

The Wife, seeking to impress, claims that her behaviour is governed by the planets (from l.609). She locates Venus as the source of her lustfulness and Mars as the source of her boldness. Both lustful and bold she declares that her planetary influences have rendered her incapable of withholding her body from any desirable man and she is bent on fuelling her sexual appetite.

Astrology was regarded as a science but became problematic if it conflicted with the Church's doctrine of free will (see The world of the Romantics > Determinism vs free will.) Chaucer seems here to be showing the Wife as sacrificing her idea of herself, as a being with free will, to a concept of herself as a being determined by planetary influence. He demonstrates the consequences of such a view by allowing her to give away the source of her economic freedom under the influence of the planets of lust and boldness.

Chaucer creates an alarming picture - a big, bold, experienced, dominating woman in search of sex. She appears invincible. But just when the Wife seems at her most powerful, Chaucer reveals her vulnerability: Jankin proves more than a match for her. The Wife loses control of the land and property which have given her independence and freedom in widowhood.

Our assessment

Dame Alison argues forcibly against misogynist views of women, yet reveals herself as a violent, dominating woman, ready to trade sex for material advantage. She is as free with her speech as she is with her sex. Ironically, she reveals herself to be the garrulous, indiscreet, deceitful ‘jangleresse' and gossip that was the frequent object of attack by male authorities (see Synopses and commentary > Part eight: l.379 ‘Lordinges, right thus' - l.452 ‘Now wol I speken').

There are three elements that might lead her hearers to judge her less harshly:

- There is a moment of poignancy in Chaucer's handling of her as she reflects on the passing of time (see Synopses and commentary > Part nine: l.453 ‘My fourthe housebonde' - l.502 ‘He is now in the grave')

- Chaucer gives the Wife a crucial and challenging point about the depiction of women in texts when she asks ‘Who painted the lion? (see Synopses and commentary > Part thirteen: l.627 ‘What sholde I seye' – l.665 ‘I nolde noght')

- The Wife's declared intention is playful and she claims that she sets out to entertain. So we might also consider that the fictional Wife is elaborating an exaggerated fiction of her marriages for the amusement of the listeners, l.193.

Non naturalistic depiction

Chaucer's characterisation of the Wife is very unlike characterisation in the nineteenth century novel. In the nineteenth century novel we become accustomed to seeing characters grow, change and learn during the course of the story. The Wife is the same kind of person at the end of the text as she is at the beginning. The difference is that we know more about her, have more examples of her behaviour and attitudes by which to judge her. In her Prologue Chaucer reveals rather develops her character.

A unique character?

Readers often warm to what they see as Chaucer's originality in his creation of the lively and irrepressible Wife. Although she is clearly Chaucer's creation, he has drawn on a literary tradition in which there is a model for the sexually experienced older woman. A comparable text would be Jean de Meun's Romance of the Rose which features an Old Woman reflecting on her strategies and her declining power. (You can find this in The Canterbury Tales ed. Kolve and Olson, 2005, Norton, New York.) Similarly, much of the Wife's speech depends on her challenge to male ‘authority' regarding women and marriage, where Chaucer could utilise the many sources of anti-feminist discussion.