John Keats, selected poems Contents

- Social and political context

- Religious and philosophical context

- Literary context

- Bright Star! Would I were steadfast as thou

- The Eve of St Agnes

- ‘Hush, hush! tread softly! hush, hush, my dear!’

- Isabella: or The Pot of Basil

- La Belle Dame Sans Merci

- Lamia

- Lines to Fanny (‘What can I do to drive away’)

- O Solitude, if I must with thee dwell

- Ode on a Grecian Urn

- Ode on Indolence

- Ode to a Nightingale

- Ode to Autumn

- Ode to Melancholy

- Ode to Psyche

- On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer

- On Seeing the Elgin Marbles

- On the Sea

- Sleep and Poetry

- Time’s sea hath been five years at its slow ebb

- To Ailsa Rock

- To Leigh Hunt

- To Mrs Reynolds’s Cat

- To My Brothers

- To Sleep

- When I have fears that I may cease to be

Revolution and war

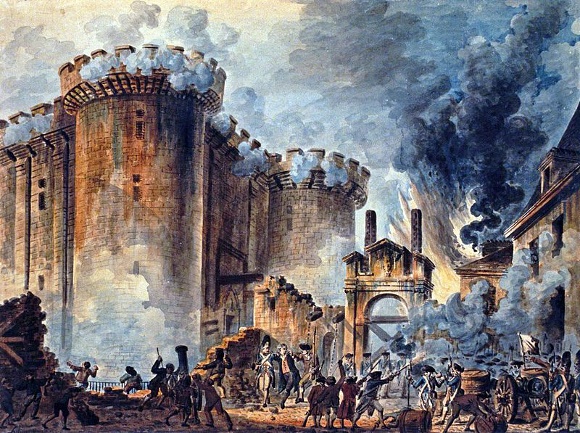

The French Revolution

Enthusiasm

Keats was born into a politically turbulent Europe. Revolution had broken out in France in 1789 (six years before Keats was born) and was greeted with enthusiasm by many people in England, including the most significant of the earlier Romantic poets - Blake, Wordsworth and Coleridge. Indeed, in his long, autobiographical poem, The Prelude, Wordsworth summed up the mood felt by many:

Keats was born into a politically turbulent Europe. Revolution had broken out in France in 1789 (six years before Keats was born) and was greeted with enthusiasm by many people in England, including the most significant of the earlier Romantic poets - Blake, Wordsworth and Coleridge. Indeed, in his long, autobiographical poem, The Prelude, Wordsworth summed up the mood felt by many: Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very Heaven!

But to be young was very Heaven!

Condemnation

However, the optimistic mood soon changed. The September Massacres of 1792, the execution of the King and Queen in 1793 and Robespierre’s Reign of Terror led to a sharp fall in British support for the Revolution, as well as to sharply divided opinions.

Amongst the leading voices condemning the revolution was Edmund Burke who published Reflections on the Revolution in France in 1790. His argument was based on the idea that men were not naturally equal and that long-established traditions and institutions should be protected.

On the other side was Thomas Paine who, in his Rights of Man, stated that no generation should feel constrained by what had happened in the past and that political power should be in the hands of the majority rather than the rich and powerful. He stated:

Every age and generation must be as free to act for itself, in all cases, as the ages and generations which preceded it. The vanity and presumption of governing beyond the grave, is the most ridiculous and insolent of all tyrannies. Man has no property in man.

Ultimately, Paine’s ideas would lead to universal male voting rights, but the government’s initial reaction was to stand firmly against any ideas of reform, a stance which was helped as news of the massacres and executions in France reached a horrified British public. Blake, Wordsworth and Coleridge all changed their attitudes, Wordsworth describing, again in The Prelude, how his early enthusiasm was transformed into a sense of betrayal.

The war with France

Britain was at war with France from 1793 to 1815, covering the whole period of Keats’ life up to the age of twenty. It was a war fought on political and ideological lines and it caused divisions in British society, with those who sympathised with reformist or radical agendas being seen by conservatives as unpatriotic or even as traitors.

Impact on British society

- The war meant that Britain became militarised to a much greater extent than had occurred in any earlier conflict:

- Some 750,000 men were drafted into the armed forces, in particular the navy

- Demand for sailors led to many men being ‘impressed’ (compelled against their will) to serve

- The women left behind often had to rely on their parish for poor relief

- The civilian population had to live with the constant fear of invasion from France.

Between October 1797 and May 1798 (when Keats was three), Napoleon was busy assembling his invasion forces on the other side of the Channel. The fear of attack was joined by other concerns, in line with Napoleon’s shifting ambitions. As Napoleon became First Consul and then (in 1804) Emperor, Britain came to see France as an aggressive imperial power that had to be stopped. Fortunately, fear of actual invasion was largely laid to rest by Nelson’s comprehensive defeat of the French fleet at Trafalgar in 1805.

Returning to ‘normality’

Napoleon abdicated in 1814, only to return from exile to be defeated at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. This left Britain trying to return to normal peacetime existence but this was not easy. Normal life had been severely disrupted and people had been forced to confront many uncomfortable ideas about the structure of British society and its serious inequalities. This ensured that the years which followed Napoleon’s defeat would be both socially turbulent and violent.

In English Literature, it denotes a period between 1785-1830, when the previous classical or enlightenment traditions and values were overthrown, and a freer, more individual mode of writing emerged.

William Blake, 1757-1827, an English Romantic poet.

(1775-1850) He was born in the Lake District and was one of the leading Romantic poets.

(1772-1834) Samuel Taylor Coleridge was a poet, critic and philosopher and as a close friend of William Wordsworth was associated with the earliest phase of poetic Romanticism.

A period of particularly violent repression by a ruler or government. This is epitomised by the French Revolution when thousands of people were killed by the guillotine.

Eighteenth century Anglo-Irish statesman, author and philosopher.

A political revolutionary and writer

Area with its own church, served by a priest who has the spiritual care of all those living within it.

Decisive naval battle of the Napoleonic Wars in which the Royal Navy, commanded by Nelson, was victorious over the French and Spanish fleets.

Decisive battle at Waterloo concluding the Napoleonic Wars.