John Keats, selected poems Contents

- Social and political context

- Religious and philosophical context

- Literary context

- Bright Star! Would I were steadfast as thou

- The Eve of St Agnes

- ‘Hush, hush! tread softly! hush, hush, my dear!’

- Isabella: or The Pot of Basil

- La Belle Dame Sans Merci

- Lamia

- Lines to Fanny (‘What can I do to drive away’)

- O Solitude, if I must with thee dwell

- Ode on a Grecian Urn

- Ode on Indolence

- Ode to a Nightingale

- Ode to Autumn

- Ode to Melancholy

- Ode to Psyche

- On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer

- On Seeing the Elgin Marbles

- On the Sea

- Sleep and Poetry

- Time’s sea hath been five years at its slow ebb

- To Ailsa Rock

- To Leigh Hunt

- To Mrs Reynolds’s Cat

- To My Brothers

- To Sleep

- When I have fears that I may cease to be

Early literary influences on Keats

Schooldays

Keats was much influenced by John Clarke, Headmaster of Enfield Academy, the school he attended from 1803 to 1811. It was here that he started reading voraciously, encouraged by Clarke and perhaps also in response to the loneliness he must have felt following the absence of his mother, followed by her death.

Clarke’s approach to education encompassed broad reading in classical and modern languages. Clarke’s beliefs and friendships also had an influence on the young Keats, bringing him into contact with the ideas of radical reformers John Cartwright and Joseph Priestley.

The Examiner

Clarke also subscribed to The Examiner, a newspaper edited by Leigh Hunt, a man who was later to become a close friend of Keats. This newspaper was published each Sunday and consisted of sixteen double-column pages. It was renowned for its incisive, witty articles and the force of its campaigns: against the slave trade, against the over-use of the death penalty and against the ‘eternal war’ with Napoleon which, amongst other things, was imposing a huge tax burden on the British. Other targets for attack included ministerial corruption, the extravagance of the royal family and the government’s refusal to allow voting rights to Roman Catholics. Leigh Hunt’s central point was that Parliamentary reform was urgently required. Only this, he said, would ‘purify the whole constitution’.

Clarke himself said that Keats’ regular and enthusiastic reading of The Examiner ‘no doubt laid the foundation of his love of civil and religious liberty.’

The school library

Clarke’s son, Cowden, wrote about the breadth and depth of his friend Keats’ reading whilst at school. He recalled Keats’ fondness for history books as well as novels and travel stories. However, the books

that were his constant recurrent sources of attraction were Tooke’s Pantheon, Lemprière’s Classical Dictionary, which he appeared to learn, and Spence’s Polymetis. This was the store whence he acquired his intimacy with the Greek mythology.

The texts Keats started to encounter as a schoolboy opened up a world of imaginative richness that remained an essential influence on him for the rest of his life. Later he wrote about the ‘realms of gold’ he found in these books, not simply a world of escapism but a source of beauty that enriches the human experience and enlarges imaginative sympathy.

After school (1811-1814)

Keats continued his friendship with John and Cowden Clarke after he had left school and joined the surgeon Thomas Hammond as an apprentice. He would often walk the four miles from Edmonton to Enflield to borrow books from the school library and to discuss them with his friends. According to Cowden Clarke, Keats ‘devoured rather than read’ the books he borrowed.

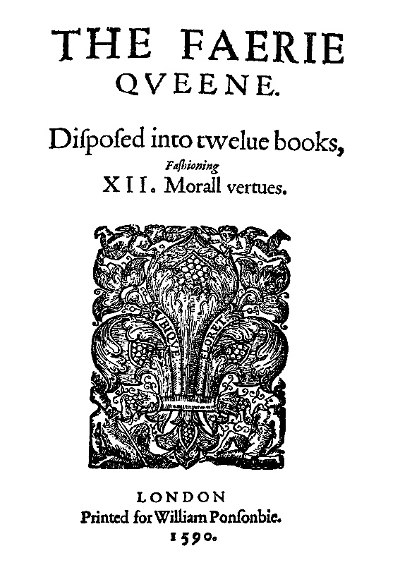

It was during this period that Keats read Ovid’s Metamorphoses as well as Virgil’s Eclogues and Milton’s Paradise Lost. But there was one book more than any other which awakened his love of poetry and which shocked him into a realisation of his own imaginative and literary powers: Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, a work first published in the 1590s.

The Faerie Queene

Spenser’s great epic poem was conceived in twelve books, each one focusing upon a Christian virtue. In fact, Spenser lived only to finish six of these books. He called it ‘an allegory or dark conceit’ and stated its aim as being ‘to fashion a gentleman or noble person’ and to do so he would portray Arthur, before he became king, as the image of a brave knight, ‘perfected in the twelve private moral virtues’, the purpose of the twelve books of the poem.

Spenser’s great epic poem was conceived in twelve books, each one focusing upon a Christian virtue. In fact, Spenser lived only to finish six of these books. He called it ‘an allegory or dark conceit’ and stated its aim as being ‘to fashion a gentleman or noble person’ and to do so he would portray Arthur, before he became king, as the image of a brave knight, ‘perfected in the twelve private moral virtues’, the purpose of the twelve books of the poem.It is easy to see how Spenser’s imaginative ambition - and the visionary world he created - would have appealed to the young Keats. Book 1 of the poem begins with

a faire Ladye in mourning weedes, riding on a white Asse, with a dwarfe behind her leading a warlike steed.

Spenser’s world is full of knights, enchantresses, hermits, dragons, floating islands and castles of brass. Keats was also intoxicated by Spenser’s linguistic richness, his eye for sensuous detail, his capacity to create dream-like visions – and his moral seriousness.

Cowden Clarke wrote that Spenser was central to Keats’ poetic development:

‘It was The Faerie Queene that awakened his genius. In Spenser’s fairy land he was enchanted, breathed in a new world, and became another being … He ramped through the scenes of that … purely poetical romance, like a young horse into a Spring meadow.

In 1814 Keats wrote his first poem, In Imitation of Spenser, in which Keats uses a Spenserian rhyme scheme and shows an awareness of the power of poetic image to create a dreamy scene:

For sure so fair a place was never seen,

Of all that ever charmed romantic eye:

It seemed an emerald in the silver sheen

Of the bright waters…

The buying and selling of slaves, historically referring to the trading of African slaves in the seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

(1769-1821). Napoleon I, Emperor of France, who conquered much of Europe but was finally defeated at the Battle of Waterloo.

Member of a worldwide Christian church which traces its origins from St. Peter, one of Jesus' original disciples. It has a continuous history from earliest Christianity.

Publius Virgilius Maro (70-19 BCE) was a Roman poet who wrote the Aeneid, an epic poem about the Trojan Wars.

An epic poem written by Virgil

43Bc- AD17. Latin poet born in Italy. His major works are Ars amatoria (Art of Love) and Metamorphoses.

(1608-1674) English poet, most famous for his epic poem, Paradise Lost.

The epic poem by the 17th-century English poet John Milton.

16th century English poet

A long narrative poem which tells some heroic story from history or myth.

The seven Christian virtues comprise the three theological virtues of faith, hope and love and the four cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, temperance and courage.

A non-realistic genre of literature whereby characters or episodes systematically represent a certain belief system. Interpretation of allegory can involve two or more levels of meaning.

An image that seems far-fetched or bizarre, but which is cleverly worked out so that the reader can understand the link.

Legendary British warrior King of the late fifth and early sixth centuries.

Someone who lives in solitude, and has little or no contact with people. Hermits devote their lives to prayer and in devotion to God.

Relating to Edmund Spenser, sixteenth century English poet, best known for his epic poem The Faerie Queene.

The ordered or regular patterns of rhyme at the ends of lines or verses of poetry.