The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale Contents

- The Prologue: introductory comments

- Part one: l.1 'Experience' - l.76 'Cacche whoso may'

- Part two: l.77 'But this word' - l.134 'To purge uryne'

- Part three: l.135 'But if I seye noght' - l.162 ' Al this sentence'

- Part four: l.163 'Up sterte' - l.192 'For myn entente'

- Part five: l.193 'Now sires' - l.234 'Of hir assent'

- Part six: l.235 'Sire old kanyard' - l.307 'I wol hym noght'

- Part seven: l.308 'But tel me this' - l.378 'This know they'

- Part eight: l.379 'Lordinges, right thus' - l.452 'Now wol I speken'

- Part nine: l.453 'My forthe housebonde' - l.502 'He is now in the grave'

- Part ten: l.503 'Now of my fifthe housebond' - l.542 'Had told to me'

- Part eleven: l.543 'And so bifel' - l.584 'As wel of this'

- Part twelve: l.585 'But now, sire' - l.626 'How poore'

- Part thirteen: l.627 'What sholde I seye' - l.665 'I nolde noght'

- Part fourteen: l.666 'Now wol I seye' - l.710 'That women kan'

- Part fifteen: l.711 'But now to purpos' - l.771 'Somme han kem'

- Part sixteen: l.772 'He spak moore' - l.828 'Now wol I seye'

- Part seventeen: The after words l.829 'The frere lough' - l.856 'Yis dame, quod'

- The Wife of Bath's Tale: Introductory comments

- Part eighteen: l.857 'In the' olde days' - l.898 'To chese weither'

- Part nineteen: l.899 'The queen thanketh' - l.949 'But that tale is nat'

- Part twenty: l.952 'Pardee, we wommen' - l.1004 'These olde folk'

- Part twenty-one: l.1005 'My leve mooder' - l.1072 'And taketh his olde wyf'

- Part twenty-two: l.1073 'Now wolden som men' - l.1105 'Ye, certeinly'

- Part twenty-three: l.1106 'Now sire, quod she' - l.1176 'To lyven vertuously'

- Part twenty-four: l.1177 'And ther as ye' - l.1218 'I shal fulfille'he Holocaust and the creation of

- Part twenty-five: l.1219 'Chese now' - l.1264 'God sende hem'

- Reaction to the Wife's Tale

- Themes in The Wife of Bath's Tale

- The struggle for power in The Wife of Bath's Prologue

- The 'wo' that is in marriage

- The portrayal of gender in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Desire and The Wife of Bath's Tale

- Is there justice in The Wife of Bath's Tale

- Social criticism in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Marriage and sexuality in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Mastery in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Debate, dispute and resolution in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Tale and teller in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

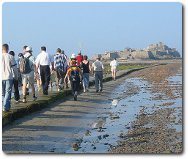

Pilgrims and pilgrimage

Who went on pilgrimage?

People from all levels of the society in which Chaucer lived went on pilgrimage. Many people would have seen pilgrimage towards a particular holy place as mirroring the journey of Christian believers through life towards God and heaven. Some visited churches near to their homes; others travelled long distances within England or even as far as Santiago de Compostela in Northern Spain, Rome or Jerusalem:

People from all levels of the society in which Chaucer lived went on pilgrimage. Many people would have seen pilgrimage towards a particular holy place as mirroring the journey of Christian believers through life towards God and heaven. Some visited churches near to their homes; others travelled long distances within England or even as far as Santiago de Compostela in Northern Spain, Rome or Jerusalem:

- Some went on pilgrimage as a specific penance

- Most went voluntarily, seeking forgiveness, spiritual encouragement or practical benefits such as healing for themselves or others

- Women often went on behalf of their family members or to ask for the ability to conceive a child

- Pilgrimage also offered a chance to escape everyday life and work and see something of the world

- Pilgrims were sometimes criticised for irresponsibility and un-spiritual behaviour.

The Canterbury Tales includes a variety of characters who vary according to rank, education, holiness and their various strengths and weaknesses. To some extent they represent the society, the beliefs and the various ideas of Chaucer's time. Pilgrims going to a shrine were supposed to behave as people on a spiritual journey but pilgrimages could also be treated as holidays and social experiences. The Tabard Inn mentioned in The Tales was a popular starting point for pilgrimage to the tomb of Saint Thomas a Becket at Canterbury.

Pilgrim destinations

Pilgrims travelled to places considered particularly holy. This might be because of:

- Association with Jesus Christ and his Apostles (such as Jerusalem, Rome or Santiago de Compostela in Spain)

- Connection with a person regarded as a saint

- The resting places of saints and their relics were believed to be places where heaven and earth intersected, where individuals might come close to God and have their prayers answered

- Saints were also believed to grant healing from a distance. This was true of St Thomas Becket and the pilgrims in Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales are said to be travelling to his shrine in Canterbury to give thanks for his help when they were sick.

More on relics: Relics are the remains of a saint, such as a bone, or articles which have been in contact with a saint and in which some of the saint's power is believed to reside. These could be articles of clothing, such as the breeches worn by St Thomas Becket which were kept at Canterbury, or dust or chippings from the saint's tomb. It was obviously very difficult to verify the authenticity of such objects so the scope for fraud was very great.