The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale Contents

- The Prologue: introductory comments

- Part one: l.1 'Experience' - l.76 'Cacche whoso may'

- Part two: l.77 'But this word' - l.134 'To purge uryne'

- Part three: l.135 'But if I seye noght' - l.162 ' Al this sentence'

- Part four: l.163 'Up sterte' - l.192 'For myn entente'

- Part five: l.193 'Now sires' - l.234 'Of hir assent'

- Part six: l.235 'Sire old kanyard' - l.307 'I wol hym noght'

- Part seven: l.308 'But tel me this' - l.378 'This know they'

- Part eight: l.379 'Lordinges, right thus' - l.452 'Now wol I speken'

- Part nine: l.453 'My forthe housebonde' - l.502 'He is now in the grave'

- Part ten: l.503 'Now of my fifthe housebond' - l.542 'Had told to me'

- Part eleven: l.543 'And so bifel' - l.584 'As wel of this'

- Part twelve: l.585 'But now, sire' - l.626 'How poore'

- Part thirteen: l.627 'What sholde I seye' - l.665 'I nolde noght'

- Part fourteen: l.666 'Now wol I seye' - l.710 'That women kan'

- Part fifteen: l.711 'But now to purpos' - l.771 'Somme han kem'

- Part sixteen: l.772 'He spak moore' - l.828 'Now wol I seye'

- Part seventeen: The after words l.829 'The frere lough' - l.856 'Yis dame, quod'

- The Wife of Bath's Tale: Introductory comments

- Part eighteen: l.857 'In the' olde days' - l.898 'To chese weither'

- Part nineteen: l.899 'The queen thanketh' - l.949 'But that tale is nat'

- Part twenty: l.952 'Pardee, we wommen' - l.1004 'These olde folk'

- Part twenty-one: l.1005 'My leve mooder' - l.1072 'And taketh his olde wyf'

- Part twenty-two: l.1073 'Now wolden som men' - l.1105 'Ye, certeinly'

- Part twenty-three: l.1106 'Now sire, quod she' - l.1176 'To lyven vertuously'

- Part twenty-four: l.1177 'And ther as ye' - l.1218 'I shal fulfille'he Holocaust and the creation of

- Part twenty-five: l.1219 'Chese now' - l.1264 'God sende hem'

- Reaction to the Wife's Tale

- Themes in The Wife of Bath's Tale

- The struggle for power in The Wife of Bath's Prologue

- The 'wo' that is in marriage

- The portrayal of gender in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Desire and The Wife of Bath's Tale

- Is there justice in The Wife of Bath's Tale

- Social criticism in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Marriage and sexuality in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Mastery in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Debate, dispute and resolution in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- Tale and teller in The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

Part twenty-three: l.1106 'Now sire, quod she' - l.1176 'To lyven vertuously'

Synopsis of l.1106-1176

The debate about ‘gentilesse'

The Old Woman then begins to answer the charges that the Knight has brought against her:

- Firstly, she takes on the Knight's notion of nobility, arguing that it is arrogant of him to believe that he is noble just because he is wealthy (l.1109-12)

- The ‘gentil' person, she claims, is the one who behaves virtuously in public and in private (l.1113-16)

- The behaviour proper to those of good and ‘gentil' birth doesn't come from wealth or from ancestry, but depends on living as Christ did (l.1117-24)

- Citing Dante as an authority, she argues that real nobility does not come from our parents, since they cannot bequeath virtuous living in the way that worldly goods can be passed down (l.1125-32)

- If it were the case that ‘gentilesse' descended through the family line, then no ‘noble' descendant would do a villainous deed – s/he would have to be true to his/her virtuous nature just as fire burns in the same way whether seen or unseen (l.1133-49)

- However, socially superior people often do ignoble deeds, no matter how much they claim to be noble, which indicates their true baseness (l.1150-61)

- So the Old Woman returns to the point that real nobility is a result of God's grace and is not dependent on status (l.1162-4).

- She quotes more ‘autoritees' who provide examples of low born people who achieved greatness because of their noble behaviour (l.1165-70)

- So she trusts that even if her ancestors were humble, God has granted her the grace to live virtuously (l.1171-76).

Commentary on l.1106-1176

The meaning of ‘Gentilesse'

In Middle English ‘gentilesse' can mean nobility of birth or rank, as well as gracious, kind, gentle or generous behaviour. What the Old Woman's argument reveals is that words cannot be confined to limited meanings. Meaning depends on context and may be open to debate. The Old Woman is arguing for a meaning of ‘gentilesse' which would consider the nobility of her character according to her gracious or generous deeds. She may be of low birth, but she hopes through God's grace to act with nobility.

The point she makes to the Knight about her definition of ‘gentilesse' as being something which cannot be passed down by inheritance is especially poignant since the Knight, who regards himself as her social superior, has committed a most ignoble act. (By contrast, in Chaucer's The Franklin's Tale, characters from different social ranks compete with each other to exercise ‘gentilesse', by offering a generous act which will release others from difficult obligations rashly incurred.)

‘Gentilesse' and the Wife of Bath

The Old Woman's definition of ‘gentilesse' would suit the Wife of Bath. Chaucer portrays her as coming from an area of increasing wealth, and therefore likely to be interested in upward social mobility unimpeded by old distinctions of nobility. (See Narrative > The portrait of the Wife of Bath in The General Prologue) On the other hand, the gracious deeds and good character essential to ‘gentilesse' do not accord with the Wife's behaviour as she describes it in her Prologue.

l.1112 Swich arrogance is nat worth an hen: In the midst of an elevated debate, the robust voice of the Wife breaks through.

l.1117, 1129 Crist [God] wole we clayme of hym oure gentillesse: The Christian argument that the nobility of humankind originates from – and is a reflection of – its divine Creator is topical. Critics of the Medieval Church such as John Wyclif argued that it should not promote its worldly status but return to the virtues of poverty and humility taught by Jesus. See Social / political context > An era of social and economic change > Challenges to the Church.

l.1121 nat biquethe, for no thyng, / To noon of us: The triple negation here highlights the finality of the Old Woman's argument.

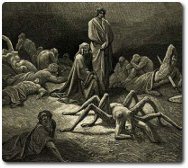

l.1125-6 the wise poete … Dant: The reference to Dante is the beginning of a section in which the Old Woman begins to cite authority to support her points. She alludes here to a section of Dante's Purgatorio (the Purgatory section of The Divine Comedy) in which Dante arrives in the so-called Valley of the Rulers, where distinguished people are doing penance for sin.

l.1125-6 the wise poete … Dant: The reference to Dante is the beginning of a section in which the Old Woman begins to cite authority to support her points. She alludes here to a section of Dante's Purgatorio (the Purgatory section of The Divine Comedy) in which Dante arrives in the so-called Valley of the Rulers, where distinguished people are doing penance for sin.

l.1128 Ful selde up riseth by his brances smale / Prowesse of man: Very seldom can anyone elevate themselves (via the insignificant increments of their family tree) by their own efforts.

l.1132 temporel thyng, that man may hurte and mayme: The Old Woman echoes the teaching of Jesus about not focusing on temporal wealth in Matthew 6: 19-21 but instead storing up heavenly wealth.

l.1140 the mount of kaukasous: The Caucasian mountains are located to the east of the Black Sea, between modern Russia and Turkey / Armenia, and represent a ‘distant place'. Medieval traders would know of them and their mention accords with the well-travelled Wife.

l.1157 He nys nat gentil, be he duc or erl: Another emphatic double negative sums up a central point of the Old Woman's argument.

l.1159-61 renomee / Of thyne auncestres … thy persone: The Old Woman suddenly shifts from general points to using direct personal pronouns to her husband.

l.1165 as seith valerius: The Wife narrates the story so that the Old Woman cites authorities that would probably have been available only in Latin – (l.1168) Seneca (a Roman philosopher), Boethius (a 6th c. philosopher, author of Consolation of Philosophy, of great interest to Chaucer) and (l.1192) Juvenal (a Roman poet). There is a problem here about the appropriateness of this to the character of the Wife. On the other hand, we do know from her Prologue that her fifth husband was a clerk so listeners might guess that she had access to these texts through her husband's accounts of them! She is an ‘aural' reader.

l.1166 tullius hostillius: a poor animal herder who ended up as king of Rome.

l.1173 the hye god … / Grante me grace: The Old Woman reiterates that virtuous living is only possible because of the undeserved gift of the God who is above all human posturing.

Investigating l.1106-1176

- How does the Old Woman define ‘gentilesse'?

- In what ways does her account of ‘gentilesse' support her appeal against the Knight's criticism of her as coming from ‘so lowe a kinde' l.1101?

- English Standard Version

- King James Version