Wuthering Heights Contents

- Social / political context

- Educational context

- Religious / philosophical context of Wuthering Heights

- Literary context of Wuthering Heights

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- Chapter 34

Emily Brontë and Victorian Britain

When was Wuthering Heights set?

The dates of events in the novel are very precisely established, from Heathcliff’s arrival in 1771 through to Lockwood’s appearance in 1801 and his final visit in 1802. We are constantly told how much time has passed and what time of year we are in. It may be that Emily Brontë set her story well before she herself was born in order to create a society which was wild and primitive and, by distancing events through time, to heighten the romantic atmosphere.

However, even when they are set in the remote past, works of fiction are shaped by the time at which they are written, published and received. The context given here, therefore, relates largely to Emily Brontë’s own lifetime.

Nineteenth century Britain: a country transformed

During Emily Brontë’s lifetime, Britain underwent changes that transformed the lives of its people:

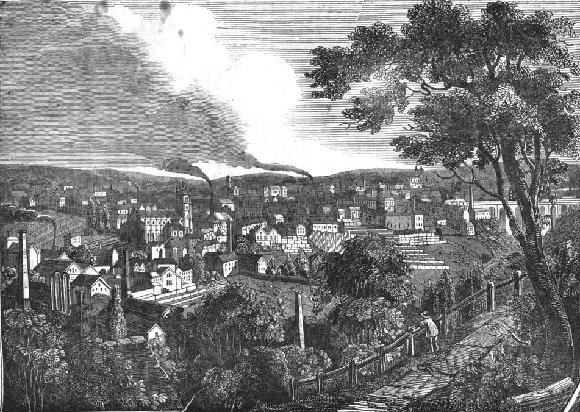

- British manufacturing became dominant in the world and trade and the financial sector also grew significantly; living in a village whose livelihood depended on wool, and which was close to the major manufacturing centres of Bradford and Halifax, the Brontës would have been very conscious of these developments

- The rail network, begun in the 1830s and largely completed by the 1870s, had a great effect not only on the accessibility of travel and speed of movement, but also on the appearance of the countryside. Wuthering Heights is set before such widening of communication; for example, Mr Earnshaw walks to Liverpool and back over three days

- British power and influence overseas expanded and seemed to be permanent; Mr Earnshaw visits Liverpool which would have been a major trading port (see also Critical approaches to Wuthering Heights: Post-colonial criticism)

- The population grew enormously, from around 12 million at the time Emily Brontë was born to nearly 20 million by the time she died

- This period also saw a significant shift of population from the countryside to the towns and the consequent growth of large cities.

An age of optimism

An age of optimism

This was a turbulent period which in many ways saw itself as a time of confident progress. Many people believed that Britain was leading the world into a new and better age, illustrated by:

- More enlightened laws

- The benefits of wealth created through industrial development (though its distribution was uneven)

- Greater political stability than in the rest of Europe, though it is worth noting that Rev. Brontë had experienced industrial unrest in his early years in Yorkshire and this is the subject of Charlotte’s novel Shirley (1849)

- The spreading of what was seen to be the ‘civilising influence’ of Christianity around the world. This was a result of the missionary impulse which developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. For example the United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel first sent missionaries to India in 1820 and to South Africa in 1821. Joseph certainly reflects this zeal, if not the desired concern for others

- Other important values included

- Deference to class and authority

- The conviction that work is a duty which is good for the soul.

Brontë and social issues

Social concerns and social reform are not central topics in Emily Brontë’s fiction. She wrote quite personally, with a relatively limited cast of characters and with none of the social breadth of, say, Charles Dickens. She did not attempt the kind of biting criticism or satire found in Dickens’ work.

This is not to say that Wuthering Heights is completely free of social concerns, but she tended to approach issues in terms of their impact on the personal lives of individuals rather than as matters of institutional reform or legislative action. In Wuthering Heights:

- The most obvious example of a social issue is the refusal of most characters to accept Heathcliff as an equal; even Nelly seems to struggle with this

- There is a clear contrast between life at Wuthering Heights (even in Mr Earnshaw’s time) and life at Thrushcross Grange

- It was expected that servants like Nelly would stay with a family through successive generations

- There is a contrast between the Yorkshire rural ways and the ways of the ‘city’; Lockwood has to get used to different mealtimes, for example

- The rights of women were severely restricted by society and by laws.

Religious attitudes to social position

Far from advocating the equality of individuals which was a feature of the Early Church, the Established Church of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries upheld the status quo. It was believed that the relative social positions of the rich and the poor came about as a result of ‘God’s appointment’; there was nothing that people could or should try to do to change the situation. Nelly, perhaps the unquestioning voice of tradition in the novel, wants to leave judgement to God and believes that people should be left as they are.

There was a popular hymn called All Things Bright and Beautiful sung by Church of England congregations and written by C. F. Alexander in 1848, the year of Emily’s death. It contains a verse summing up these sentiments:

The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

God made them, high and lowly,

And ordered their estate.

All things bright and beautiful,

All creatures great and small,

All things wise and wonderful,

The Lord God made them all.

Emily Brontë herself seems to believe in equality through common humanity, and in the ability of people to change. However, this view does not seem to arise from religious conviction, or at least not through orthodox Christian understanding of the time. We are told that she would sit with her back to the pulpit whilst her father was preaching! She did not find her father’s austere version of religion attractive and she satirised this through the ‘self-righteous Pharisee’ Joseph.

The right use of wealth

Wealth is not seen as a sign of quality of character in Wuthering Heights. The Lintons appear to be spoiled and snobbish as is clearly shown from our first meeting with them in Chapter 6. Catherine’s decision to marry Edgar because of the money and style which such a marriage offers does not seem to improve her character, despite her avowed intention to use her wealth to ‘aid Heathcliff to rise’.

Brontë is not concerned with how Heathcliff makes himself a wealthy gentleman, but more with how he uses the power that it brings in order to pursue his revenge.