Songs of Innocence and Experience Contents

- Social / political context

- Religious / philosophical context

- Literary context

- Textual history

- Songs of Innocence

- Introduction (I)

- The Shepherd

- The Ecchoing Green

- The Lamb

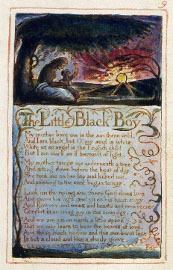

- The little black boy

- The Blossom

- The chimney sweeper (I)

- The little boy lost (I)

- The Little Boy Found

- Laughing song

- A Cradle Song

- The Divine Image

- Holy Thursday (I)

- Night

- Spring

- Nurse's Song (I)

- Infant Joy

- A Dream

- On Another's Sorrow

- Songs of Experience

- Introduction (E)

- Earth's Answer

- The Clod and the Pebble

- Holy Thursday (E)

- The Little Girl Lost

- The Little Girl Found

- The Chimney Sweeper (E)

- Nurse's Song (E)

- The Sick Rose

- The Fly

- The Angel

- The Tyger

- My Pretty Rose-tree

- Ah! Sun-flower

- The Lilly

- The Garden of Love

- The Little Vagabond

- London

- The Human Abstract

- Infant Sorrow

- A Poison Tree

- A Little Boy Lost (E)

- A Little Girl Lost

- To Tirzah

- The Schoolboy

- The Voice of the Ancient Bard

- A Divine Image

The Little Black Boy - Synopsis and commentary

Synopsis of The Little Black Boy

An African child compares his outward appearance with a white child's, but asserts that his soul is white. He then recounts his mother's teaching. She taught him to think of heaven where God gives comfort and joy. Life is about learning to accept love. Bodies are only like clouds which will disappear once people have learned to ‘bear the beams of love'. Then God will call individuals to himself, where they will rejoice like innocent lambs.

The boy then turns to address a white boy. When they are both in heaven, he will shade his companion from the heat of God's love until the child can bear to be at God's knee. Then the black child will stroke the white child's hair. He will be like the white child then and so the white boy will love him.

This is, among other things, an attack by Blake on contemporary attitudes to race and slavery. (See Religious / philisophical background > Blake's religious world > Dissenting attitudes to Locke.) Many at the time believed that non-white races were inferior and used this to justify slavery. Here Blake deals with a contemporary social evil but also shows how ways of thinking can reinforce a person's subjection to evil.

Commentary

Blake attacks the eighteenth century belief in racial inferiority by asserting the insubstantial, ephemeral nature of the body. He believed that bodies were simply vapours masking the true self.

More on the status of the body: Blake's belief reflects one aspect of Christian teaching, that bodies were merely frail clay vessels which contained the permanent knowledge of God (2 Corinthians 4:6-7). However, Blake seems to ignore the biblical value placed on physicality, shown by God taking human form as Jesus Christ.

By stressing the common human nature shared by the boys, and their equality before God, Blake is also presenting black and white as contraries rather than oppositions in human nature. This, too, undermines the philosophy used to justify slavery.

The existing status quo

The tone and approach of the young speaker, however, suggests an uncomplaining acceptance of the injustice behind this judgement of inferiority. He has been taught not to protest but to think of future happiness with God. He is offered future joy to persuade him to accept present injustice. Furthermore, the child accepts that he will have to become like the white boy in order to be loved by him. Whiteness sets the standard. To be loved is to accept the white boy's terms.

Here, Blake is exposing the limitations of innocence. Lacking awareness, the innocence of the black boy makes him vulnerable to injustice and exploitation.

Subversive imagery

When Blake employs the imagery of God's love and sunbeams, so that accepting love means becoming ‘sunburnt', he turns the tables on his contemporaries. According to Blake, the black boy has evidently borne more sun than the white child. He has therefore been more receptive to the beams of God's love. Similarly, in heaven, it is the black boy who is the noble, loving and generous one, seeing himself as protecting the white boy until he can bear the heat.

Blake here seems to be satirizing the approach of contemporary Christianity, as well as attacking notions of white superiority.

Investigating attitudes to race

- Discuss whether you think this poem has any valid arguments against racism.

- English Standard Version

- King James Version