Songs of Innocence and Experience Contents

- Social / political context

- Religious / philosophical context

- Literary context

- Textual history

- Songs of Innocence

- Introduction (I)

- The Shepherd

- The Ecchoing Green

- The Lamb

- The little black boy

- The Blossom

- The chimney sweeper (I)

- The little boy lost (I)

- The Little Boy Found

- Laughing song

- A Cradle Song

- The Divine Image

- Holy Thursday (I)

- Night

- Spring

- Nurse's Song (I)

- Infant Joy

- A Dream

- On Another's Sorrow

- Songs of Experience

- Introduction (E)

- Earth's Answer

- The Clod and the Pebble

- Holy Thursday (E)

- The Little Girl Lost

- The Little Girl Found

- The Chimney Sweeper (E)

- Nurse's Song (E)

- The Sick Rose

- The Fly

- The Angel

- The Tyger

- My Pretty Rose-tree

- Ah! Sun-flower

- The Lilly

- The Garden of Love

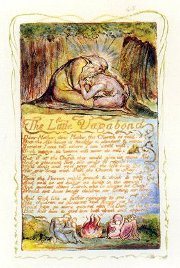

- The Little Vagabond

- London

- The Human Abstract

- Infant Sorrow

- A Poison Tree

- A Little Boy Lost (E)

- A Little Girl Lost

- To Tirzah

- The Schoolboy

- The Voice of the Ancient Bard

- A Divine Image

The Little Vagabond - Synopsis and commentary

Synopsis of The Little Vagabond

A poor child (who, as a vagabond, is likely to have received charity from church) is telling his mother why he does not find church appealing. S/he compares it with the ale-house (which, in Blake's time, would have been criticised by the church as a place of wrongdoing). This is truly warm and welcoming and makes the child feel valued (‘used well').

The church is both physically and emotionally cold. If it offered warmth and ale (sources of human satisfaction), people would be happy to be there all day. If the parson would drink and sing as well as preach, the people would be happy to hear him. Similarly, the teacher of the school, Dame Lurch, would not be so fierce towards her charges. They would be healthy (from eating properly) rather than ‘bandy' (suggesting a condition, associated with malnutrition, called rickets). She would neither keep them short of food, through religious fasting, nor punish them so often with the cane.

The child suggests that God would be happy to see his children happier and so should drop his antagonism to the Devil and alcohol. He envisages God being reconciled with the Devil and treating him as the father figure does his son in a famous parable, giving drink, clothes and a welcome as to an estranged member of the family. (See Famous stories from the Bible > The Prodigal Son)

Commentary

This poem uses a specific situation, the attractiveness of the ale-house to the urban poor, to explore the way in which Blake's contemporary social system denied them the possibility of human satisfaction. In particular, the strictures of organised religion are attacked.

Interpretations

Some critics see the poem as an assertion of the rights of the body over the moralistic approach to it espoused by the traditional Christianity of Blake's time. Some find the poem difficult because they find the child's vision of happiness inadequate and materialistic. Others feel that such a response is exactly the attitude that Blake is attacking.

You could say that the boy represents the same attitude expressed by Sir Toby Belch in Twelfth Night, in the face of the joyless life-denial of Malvolio:

Blake is not claiming here that the boy represents a full or total vision of life. He offers, however, a necessary aspect of human experience to offset the puritanical denial of the flesh.

For some critics, the child is too glib and ‘knowing' to be entirely trustworthy. However, this is a poem of ‘experience'. The boy is not an innocent whose unawareness makes him vulnerable to exploitation. As a vagabond, he is a child who has experienced what ‘love' and ‘charity' mean in his society. With the absence of a father figure to provide for him and his mother (or if she is neglectful), he is likely to have experienced dependence upon the charity of the parish.

Investigating The Little Vagabond

- Do you find the child is too glib and ‘knowing' to be entirely trustworthy?

- Explain your conclusion.