Wilfred Owen, selected poems Contents

- Wilfred Owen: Social and political background

- Wilfred Owen: Religious / philosophical context

- Wilfred Owen: Literary context

- Wilfred Owen: 1914

- Wilfred Owen: Anthem for Doomed Youth

- Wilfred Owen: At a Calvary near the Ancre

- Wilfred Owen: Disabled

- Wilfred Owen : Dulce et Decorum Est

- Wilfred Owen: Exposure

- Wilfred Owen: Futility

- Wilfred Owen: Greater Love

- Wilfred Owen: Hospital Barge

- Wilfred Owen: Insensibility

- Wilfred Owen: Inspection

- Wilfred Owen: Le Christianisme

- Wilfred Owen: Mental Cases

- Wilfred Owen: Miners

- Wilfred Owen: S.I.W

- Wilfred Owen: Soldier’s Dream

- Wilfred Owen: Sonnet On Seeing a Piece of Our Heavy Artillery Brought into Action

- Wilfred Owen: Spring Offensive

- Wilfred Owen: Strange Meeting

- Wilfred Owen: The Dead-Beat

- Wilfred Owen: The Last Laugh

- Wilfred Owen: The Letter

- Wilfred Owen: The Parable of the Old Man and the Young

- Wilfred Owen: The Send-Off

- Wilfred Owen: The Sentry

- Wilfred Owen: Wild with All Regrets

Nationhood

The monarchy

When troops enlisted to fight in the First World War, they were fighting for King and Country in that order. Attitudes to the monarchy in 1914 had been strongly influenced by the reigns of the previous two monarchs, Queen Victoria (1837-1901) and Edward VII (1901-10). Queen Victoria was seen as the mother of the Empire and her own family values were taken as a role model for many. Her husband, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg, was German and she was known as the ‘grandmother of Europe’ since so many of her children married into European Royalty. The monarchs of the warring nations of the First World War - Britain, Germany and Russia - were all cousins.

George V (1910-36) and Queen Mary were highly regarded, and King George V disassociated himself from his German cousins and changed the name of the Royal House of Saxe-Coburg Gotha to the Royal House of Windsor.

The British Empire

When Britain went to war in 1914, it wasn’t just one nation involved but the entire British Empire. This had grown through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries until it covered one quarter of the surface of the globe and ruled over one fifth of the earth’s population. Queen Victoria (1837-1901) was said to rule over an empire on which the sun never set and in 1877 was crowned Empress of India. In its heyday the Empire was the largest ever known and had huge power and influence.

Bolstered by her Empire, Britain had maintained a ‘splendid isolation’ from the rest of Europe. However, by the start of the twentieth century, Edwardian Britain was beginning to feel the strain of standing alone. In the face of increasing militarism in Germany, as well as their rapid industrial development, Edward VII (1901-10) signed the Entente Cordiale with France in 1904, followed by the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907. By the time George V became king in 1911, the development of Germany’s military capability was considered a serious threat.

When war was declared in 1914, the British Empire called on troops from the ‘far flung corners’ of the Empire - the dominions of Canada, Newfoundland, India, Australia, New Zealand, the West Indies and South Africa. The number of men enlisting from the colonies was in the region of 2.3 million.

Empires clash

Faced with the might of the British Empire and the extent of Russian territories, the German Kaiser, Wilhelm II (popularly referred to as ‘Kaiser Bill’ in the UK) aimed to make Germany into a world power too. His foreign policy goal of Weltpolitik would be achieved through the growth of a superior navy which could head up Germany’s attempt to gain colonies. Germany believed it needed more Lebensraum, its own ‘place in the sun’, for its natural development.

The shrinking globe

Developments in scientific instrumentation over the nineteenth century had allowed cartography to become an exact science. As a result of accurate maps and the recording of every part of the known world, people’s perception of their world was that it had become smaller. Although most people could not afford to travel there was a sense of knowing more about the rest of the world.

In 1916 the Russian revolutionary Lenin wrote a pamphlet on imperialism in which he described the ‘shrinking globe’ as creating or strengthenuing rivalries among political powers for ‘the few exploitable places’ that remained. Germany’s desire for expansion could not but threaten the other world empires.

Dissatisfaction

Although Britain could call on a strong imperial and patriotic fervour to support its resistance to Germany, there was a wide variety of groups which opposed the war. These included Marxists and Christians, pacifists and anarchists. In the UK there were about sixteen thousand ‘conchies’ or ‘conscientious objectors’ who refused to bear arms or kill. Against a strongly pro-war national mood, such men were vilified both by the press and in their local communities.

Ireland

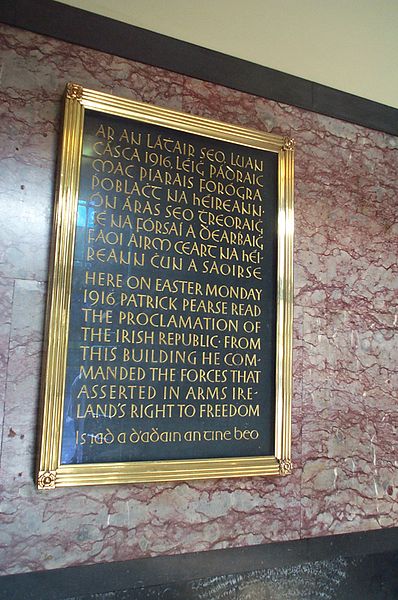

Others were opposed to being ruled by the British Government in the first place, let alone being prepared to die for them. Although over 200,000 Irish men fought in WWI and all of Ireland was officially part of the UK, many Catholics in Ireland had been seeking Home Rule since the end of the nineteenth century. Resistance to this from Westminster resulted in the Irish rebellion, which came to a head with the Easter Rising of 1916 in Dublin. Fierce British reaction made martyrs of the Rising’s leaders and after the First World War was over, the Irish War of Independence (1919-21) led to the separation of southern Ireland (now Eire) from British rule.

The ambivalence of many Irish to the war effort is illustrated by W.B.Yeats’ An Irish Airman Foresees His Death.