Articles

- Impact of the Bible

- The cultural influence of the Bible and Christianity in England

- Bible in English culture, The

- English Bible Translations

- Influence of the Book of Common Prayer on the English language

- A history of the church in England

- Culture and sung Christian worship

- Famous stories from the Bible

- Literary titles from the Bible

- Common Sayings from the Bible

- Big ideas from the Bible

- Adoption

- Angels

- Anger

- Anointing

- Apocalypse, Revelation, the End Times, the Second Coming

- Armour

- Ascent and descent

- Atonement and sacrifice

- Babel, language and comprehension

- Baptism

- Betrayal

- Blood

- Bread

- Bride and marriage

- Cain and Abel

- Christians

- City and countryside

- Cleansing

- Clothing

- Community, church, the body of Christ

- Covenant

- Creation, creativity, image of God

- Cross, crucifixion

- Curtain/veil

- Darkness

- Death and resurrection

- Desert and wilderness

- Devils

- Donkey, ass

- Doubt and faith

- Dove

- Dreams, visions and prophecy

- Earth, clay, dust

- Exile

- Feasting and fasting

- Fire

- Forgiveness, mercy and grace

- Fruit, pruning

- Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve, 'Second Adam'

- Gateway, door

- Goats

- Grass and wild flowers

- Harvesting

- Heaven

- Hell

- Incarnation (nativity)

- Inheritance and heirs

- Jewels and precious metals

- Jews, Hebrews, Children of Israel, Israelites

- Journey of faith, Exodus, pilgrims and sojourners

- Judgement

- Justice

- Kingship

- Last Supper, communion, eucharist, mass

- Light

- Lion

- Lost, seeking, finding, rescue

- Messiah, Christ, Jesus

- Miracles

- Mission, evangelism, conversion

- Moses

- Music

- Names

- Noah and the flood

- Numbers in the Bible

- Parables

- Parents and children

- Passover

- Path, way

- Patriarchs

- Peace

- Penitence, repentance, penance

- Poverty and wealth

- Prayer

- Promised Land, Diaspora, Zionism

- Psalms

- Rabbi, Pharisee, teacher of the law

- Redemption, salvation

- Rest

- Rock and stone

- Salt

- Seed, sowing

- Serpent, Devil, Satan, Beast

- Servant-hood, obedience and authority

- Sheep, shepherd and lamb

- Sin

- Slavery

- Soul

- Temple, tabernacle

- Temptation

- Ten Commandments, The

- Trees

- Trinity, Holy Spirit

- Vine, vineyard

- Water

- Weeds, chaff, briar, thorn

- Wisdom and foolishness

- Women in the Bible

- Word of God

- Work and idleness

- Investigating the Bible

- Literary allusions to the Bible

- Pilgrimage in literature

- Biblical style in poetry

- Biblical imagery in metaphysical poetry

- Bible/Literature intertextuality

- The cultural influence of the Bible and Christianity in England

Harvesting

Harvest was a profoundly important part of community life for the cultures represented in the Bible. Lives depended on crop success and, unaided by modern technological innovations, the work of growing and reaping was the employment of a large proportion of the population.

The ancient Israelites recognised the providence of God in the production of food from the land. Harvest was therefore a time of thanksgiving and offering. The idea of harvest also carries considerable metaphorical significance — sometimes positive (e.g. in the context of evangelism), sometimes mixed or negative (e.g. in the context of judgement, or of the consequences of sin).

Providence, celebration and generosity

The Bible affirms that it is God who causes the earth to supply the food needs of his creation Psalms 104:14-15, 2 Corinthians 9:10.

Feasts

Special festivals are scheduled in to the agricultural calendar to encourage the ongoing recognition of God’s provision. The start of the harvest is marked by the Feast of First-fruits, at which the early crops are given as an offering Leviticus 23:9-12. Fifty days later the Feast of Weeks (Pentecost) is celebrated – another occasion for offering produce and expressing gratitude Leviticus 23:15-18.

Tithing

Another way in which God’s people are to honour him with their harvest wealth is through tithing. A tenth (at least) of each household’s crops and livestock are devoted to God Leviticus 27:32. The income is used for the upkeep of the tabernacle/Temple and the Levites who serve there Numbers 18:21-28, and to help the poor Deuteronomy 26:12-13.

Social justice

Social justice

The Biblical equivalent of ‘social security’ includes provision for gleaning. Farmers are not to harvest their fields and vineyards exhaustively, but are to leave the edges, and anything not picked up on a ‘first pass’, for the poor and for needy visitors Leviticus 19:9-10.

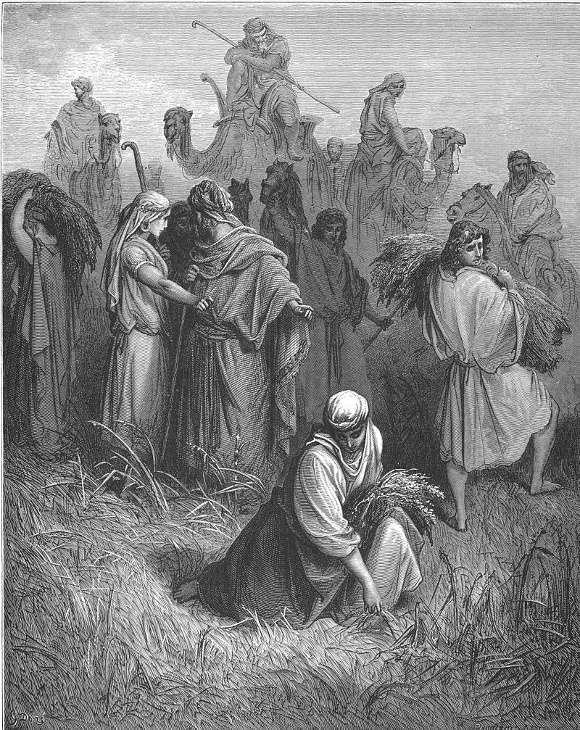

This practice forms the backdrop for the story of Ruth. Left a widow, with a widowed mother-in-law to support, she resorts to gleaning in a field Ruth 2:1-7. Boaz, the field owner and a relative of her late husband, extends protection and support beyond the require-ments of the law Ruth 2:14-18, eventually marrying her Ruth 4:13.

Metaphorical harvesting

Consequences of human action

Just as working the land (well or poorly) bears fruit in a literal harvest (of varying quantity or quality), so the Bible states that people’s actions and attitudes in life produce a metaphorical harvest, for good or ill: (Galatians 6:7)

Evangelism

When Jesus sent his disciples out ahead of him into the towns and villages he planned to visit, he compared them to workers bringing in a harvest Luke 10:2. The parable of the sower (Matthew 13:1-9, explained in Matthew 13:18-23) compares the ‘word of the kingdom’ with seed that is sown in different terrain. ‘Good soil’ corresponds to a hearer who understands the word and yields an increase.

Judgement

In the Old Testament, Joel describes the ‘judgement of the nations’ through war by using a harvest metaphor:

Go in, tread, for the winepress is full.

The vats overflow, for their evil is great.

Joel 3:13 ESVUK

This image is echoed in the New Testament in the context of the final judgement Revelation 14:14-16.

Jesus compares God’s delayed judgement against sin to a farmer whose field is infiltrated by weeds. At harvest time the weeds will be gathered and burned, but in the meantime they are allowed to grow alongside the crop – otherwise the crop may also be damaged in the process of destroying the weeds Matthew 13:24-30; Matthew 13:37-42.

Harvesting in literature

- In the American South during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the flourishing cotton, tobacco and sugar industries relied on slave labour to work the plantations. Gruelling descriptions of enforced harvest labour feature in many novels about slavery:

- Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1852) describes plantation life under varying degrees of cruel treatment. The book was influential in abolishing the slave trade but also contributed towards naive and damaging racial stereotypes

- Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987) is an example of ‘magical realism’. It tells the story of an escaped slave who is haunted by the baby whom she killed to protect from her white masters

- Konstantin Levin, the co-protagonist of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (1877), is a landowner who enjoys participating in manual field labour alongside his peasant workers

- The Grapes of Wrath (1939) by John Steinbeck tells the story of a Oklahoma family displaced by a period of severe dust storms known as the Dust Bowl. The storms wrecked many harvests in a large region of the US and forced farmers out of their homes to seek work in better-off states

- In Marilynne Robinson’s 2014 novel Lila, the title character lives for many years as a ‘drift-er’. She and her occasional companions support themselves via ad-hoc field and orchard work as they wander the countryside.

Other

- The Gleaners is a 1857 oil painting by Jean-François Millet depicting three peasant women picking up the stray grains of wheat left after the harvest

- The Wheat Fields is a whole series by Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) expressing his sense of connection to nature and his respect for manual labourers.

Related topics

- Big ideas: Feasting and fasting; Grass and wild flowers; Judgement; Mission, evangelism, conversion; Parables; Poverty and wealth; Seed, sowing; Vine, vineyard; Weeds, chaff, briar, thorn

- Famous stories from the Bible: A time for everything; Parable of the sower; Ruth and Naomi return;

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

- English Standard Version

- King James Version

Set in the time of the judges, a story of the faith of a Moabite girl and her sacrificial love for her Jewish mother-in-law. Descended from Ruth is King David, the ancestor of Christ the Messiah.

Big ideas: Women in the Bible

Includes visions of a plague of locusts and devastating drought in Israel, seen as signs of the coming day of the Lord when God will punish his enemies; followed by promises of restoration, blessing and the outpouring of God's spirit on all people.

Big ideas: Dreams, visions, prophecy

Recently Viewed

-

Harvesting

now