The Color Purple Contents

- The Color Purple: Social and political context

- The Color Purple: Religious and philosophical context

- The Color Purple: Literary context

- Textual help

- Letter 1

- Letter 2

- Letter 3

- Letter 4

- Letter 5

- Letter 6

- Letter 7

- Letter 8

- Letter 9

- Letter 10

- Letter 11

- Letter 12

- Letter 13

- Letter 14

- Letter 15

- Letter 16

- Letter 17

- Letter 18

- Letter 19

- Letter 20

- Letter 21

- Letter 22

- Letter 23

- Letter 24

- Letter 25

- Letter 26

- Letter 27

- Letter 28

- Letter 29

- Letter 30

- Letter 31

- Letter 32

- Letter 33

- Letter 34

- Letter 35

- Letter 36

- Letter 37

- Letter 38

- Letter 39

- Letter 40

- Letter 41

- Letter 42

- Letter 43

- Letter 44

- Letter 45

- Letter 46

- Letter 47

- Letter 48

- Letter 49

- Letter 50

- Letter 51

- Letter 52

- Letter 53

- Letter 54

- Letter 55

- Letter 56

- Letter 57

- Letter 58

- Letter 59

- Letter 60

- Letter 61

- Letter 62

- Letter 63

- Letter 64

- Letter 65

- Letter 66

- Letter 67

- Letter 68

- Letter 69

- Letter 70

- Letter 71

- Letter 72

- Letter 73

- Letter 74

- Letter 75

- Letter 76

- Letter 77

- Letter 78

- Letter 79

- Letter 80

- Letter 81

- Letter 82

- Letter 83

- Letter 84

- Letter 85

- Letter 86

- Letter 87

- Letter 88

- Letter 89

- Letter 90

The American Black Power movement

An alternative strategy

Although the Civil Rights Movement achieved some major goals by means of non- violent protest demonstrations, many black communities began to rebel, often violently, against white authority.

Black radicals believed that black citizens should be more assertive. They adopted slogans such as ‘Black is Beautiful’ and ‘Black Power!’ arguing that African-Americans should take control of their own lives and not wait until white America was prepared to make some changes towards racial equality.

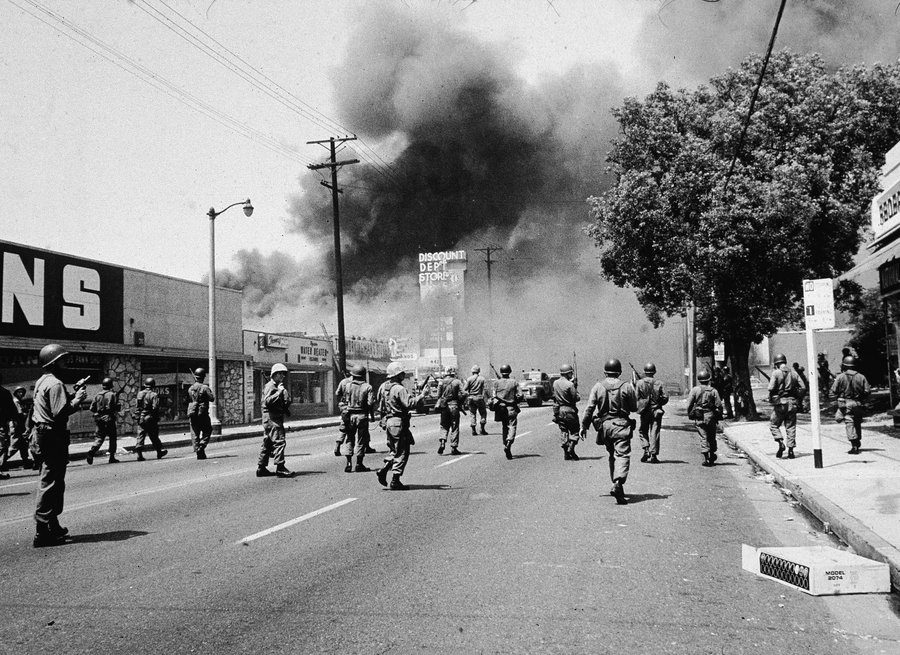

The Watts riots (1965)

At the height of the civil rights movement, some black communities rebelled violently against white authority.

At the height of the civil rights movement, some black communities rebelled violently against white authority.

Five days after President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law, the black neighbourhood of Watts, in Los Angeles California, erupted into a six day uprising. Thirty four people were killed, one thousand injured and four thousand citizens were arrested.

The violence in Watts was caused by frustrations in black inner-city communities in the North and the West, where poor housing and employment discrimination, combined with intense racial bigotry, kept black people living in poverty.

The second phase of the civil rights movement became a period of militancy, with calls for black power, rather than non-violent protest.

We shall overrun!

Organizations such as the Nation of Islam, the Black Panther Party and a newly militant SNCC tapped into the frustrations of urban black populations. Many people chose to join these groups, prepared to arm themselves and enter a more violent phase of the black struggle for freedom. The pacifist protest message of ‘We shall overcome’ was replaced by black power’s new slogan – ‘We shall overrun!’

Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam

Rejecting ‘white religion’

The Nation of Islam was an organisation of black radical political activists that rejected Christianity as a white man's religion and encouraged black Americans to convert to and to follow the teachings of Islam. Members of the movement believed that the only way for black Americans to achieve freedom, justice and equality was the establishment of a totally separate black state.

Rejecting ‘white identity’

The most well-known member of the organisation was Malcolm Little, more famously known as Malcolm X, an alias that symbolised a complete rejection of white society. Malcolm X argued that as a descendant of slaves captured in Africa, his real surname had been lost and replaced by the surname given to his family by the slave owners. As a symbol of protest he refused to use or recognise his 'slave name' and called himself X instead.

Rejecting ‘white society’

The Nation of Islam claimed that white society was racist and corrupt. Malcolm X urged black Americans to reject white society, and form a distinct, and in his view, better society of their own.

In 1964 Malcolm X gave a public speech called ‘The Ballot or the Bullet’ which advised African-Americans to exercise their right to vote. He stated that if the government continued to prevent African-Americans from achieving full equality, it might be necessary for the latter to take up arms.

Malcolm X’s development

After ten years as chief spokesman for the Nation of Islam, becoming increasingly frustrated by the slow progress of the organisation in achieving its stated aims, Malcolm X resigned from NOI in March 1964.

He undertook a pilgrimage, going first to Africa, then on to Mecca, to perform the Hajj. It was during this time that his beliefs changed and he realised that many of his fellow pilgrims were in fact white and their opinions and beliefs were similar to his own.

More on the Hajj: The Hajj is a ritual that strengthens the bonds of Muslim brotherhood and sisterhood by showing that everyone is equal in the eyes of Allah (God).

Malcolm X returned to America and on 21 February 1965, while speaking at a rally in New York, he was assassinated by members of the Nation of Islam.

The Black Panther Party (BPP)

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (sic), later renamed the Black Panther Party or BPP, was a revolutionary left-wing political organisation that was active from the mid-sixties until the early 1980s. It was founded in 1965, after the assassination of Malcolm X, by two college students, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, in West Oakland, California.

Originally the BPP organised armed inner-city citizens' patrols to monitor police activities in black areas and to challenge police brutality. By 1969 community social programmes such as community health clinics and the Free Breakfast for Children Programs (sic) had been introduced.

FBI opposition and COINTELPRO

The 1960s director of the Federal Bureau of Intelligence (FBI), J Edgar Hoover, accused the BPP of being ‘the greatest threat to the internal security of the country’, seeing it as a dangerous and subversive communist organisation and therefore an enemy of the United States government. An active counter intelligence campaign by FBI agents against the BPP (known as COINTELPRO) was so extreme that years later, when details of it were revealed, a public apology for ‘wrongful uses of power’ was made by the current FBI director.

The Ten-Point Program (1967)

The BPP published a ten point programme of ‘What We Want Now!’ in 1967. Their demands were:

- Freedom and power to decide the destiny of the black community

- Full employment for black people

- An end to ‘the robbery by the white men’ of the black community

- Decent housing, ‘fit for shelter of human beings’

- Education that teaches black people their ‘true history’

- Black men to be exempt from service in the armed forces

- An end to ‘POLICE BRUTALITY’ (sic) and ‘MURDER’ (sic) of black people

- Freedom for all black men held in jail

- All black people to be tried in court ‘by a jury of their peers or people from their black communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States’

- ‘Land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.’

Black masculinity

At its outset, the BPP affirmed black masculinity and traditional gender roles. The use of guns and violence, together with the party’s agenda of armed resistance, was seen by the organisation’s predominantly male membership as proof of manhood. In 1968, the BPP newspaper stated in several articles that the role of female Panthers was to ‘stand behind black men’ and be supportive.

As the feminist movement developed and its influence became stronger, a significant shift in perspective occurred. In 1969, the same newspaper issued an instruction to male Panthers that in future, black women were to be treated as equals, condemning sexism as ‘counter-revolutionary’.

The BPP adopts womanism

The party then went further, by adopting a ‘womanist’ ideology, in consideration of the unique experiences of African-American women. Womanism promoted the point of view that black men and women hold different positions in the home and community which enable them to work together equally for the preservation of African-American culture. Since traditional white feminism failed to include race and the class struggle in its condemnation of male sexism, it was therefore part of white hegemony and thus dismissed by the BPP as an invalid ideology.

Womanism and Africana womanism

The term ‘womanism’ was used by Alice Walker in a 1979 short story, ‘Coming Apart’ and she has been credited with its invention. An alternative definition of ‘Africana womanism’, coined by Clenora Hudson-Weems, is thought to be a better explanation of the male/female alliance within the BPP. The addition of ‘Africana’ identified the race of the woman and firmly established her cultural identity.

The end of the road

Although the aims of the BPP were in many ways admirable, the party failed to achieve many of its objectives because they were regarded as too radical. While members saw themselves as revolutionaries, they did not fully understand the importance of persuading the community to support their revolutionary ideals. Co-founder Huey Percy Newton (1942 – 1989) regretted that ‘the people did not follow our lead in picking up the gun.’

Why the BPP failed

- By demanding the right to carry arms and adopting violence as a legitimate form of self-defence, the Panther Party inevitably became a target of government repression

- The organisation’s public activities often made it easy for the government and the media to represent them as a violent, terrorist group and therefore an enemy of the American way of life

- The group’s activities, compared to other more moderate, non-violent civil rights movements, alienated not only the white population, but also many male and female black Americans

- The group’s original aggressively masculine ideology was sometimes viewed as sexism, thereby alienating women in the black community

- Lack of public support from the white community, together with the effect of media representation and the COINTELPRO operations of the FBI, reduced support for the party

- Lack of resources, often claimed to be the result of internal mismanagement of funds, reduced the organisation’s impact and its ability to deliver its social welfare programmes

- The BPP lacked the cohesive public support required to instigate change that was given to other more moderate movements, such as those headed by Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.