The Color Purple Contents

- The Color Purple: Social and political context

- The Color Purple: Religious and philosophical context

- The Color Purple: Literary context

- Textual help

- Letter 1

- Letter 2

- Letter 3

- Letter 4

- Letter 5

- Letter 6

- Letter 7

- Letter 8

- Letter 9

- Letter 10

- Letter 11

- Letter 12

- Letter 13

- Letter 14

- Letter 15

- Letter 16

- Letter 17

- Letter 18

- Letter 19

- Letter 20

- Letter 21

- Letter 22

- Letter 23

- Letter 24

- Letter 25

- Letter 26

- Letter 27

- Letter 28

- Letter 29

- Letter 30

- Letter 31

- Letter 32

- Letter 33

- Letter 34

- Letter 35

- Letter 36

- Letter 37

- Letter 38

- Letter 39

- Letter 40

- Letter 41

- Letter 42

- Letter 43

- Letter 44

- Letter 45

- Letter 46

- Letter 47

- Letter 48

- Letter 49

- Letter 50

- Letter 51

- Letter 52

- Letter 53

- Letter 54

- Letter 55

- Letter 56

- Letter 57

- Letter 58

- Letter 59

- Letter 60

- Letter 61

- Letter 62

- Letter 63

- Letter 64

- Letter 65

- Letter 66

- Letter 67

- Letter 68

- Letter 69

- Letter 70

- Letter 71

- Letter 72

- Letter 73

- Letter 74

- Letter 75

- Letter 76

- Letter 77

- Letter 78

- Letter 79

- Letter 80

- Letter 81

- Letter 82

- Letter 83

- Letter 84

- Letter 85

- Letter 86

- Letter 87

- Letter 88

- Letter 89

- Letter 90

The Women’s Liberation movement

Origins and ideologies

Feminism

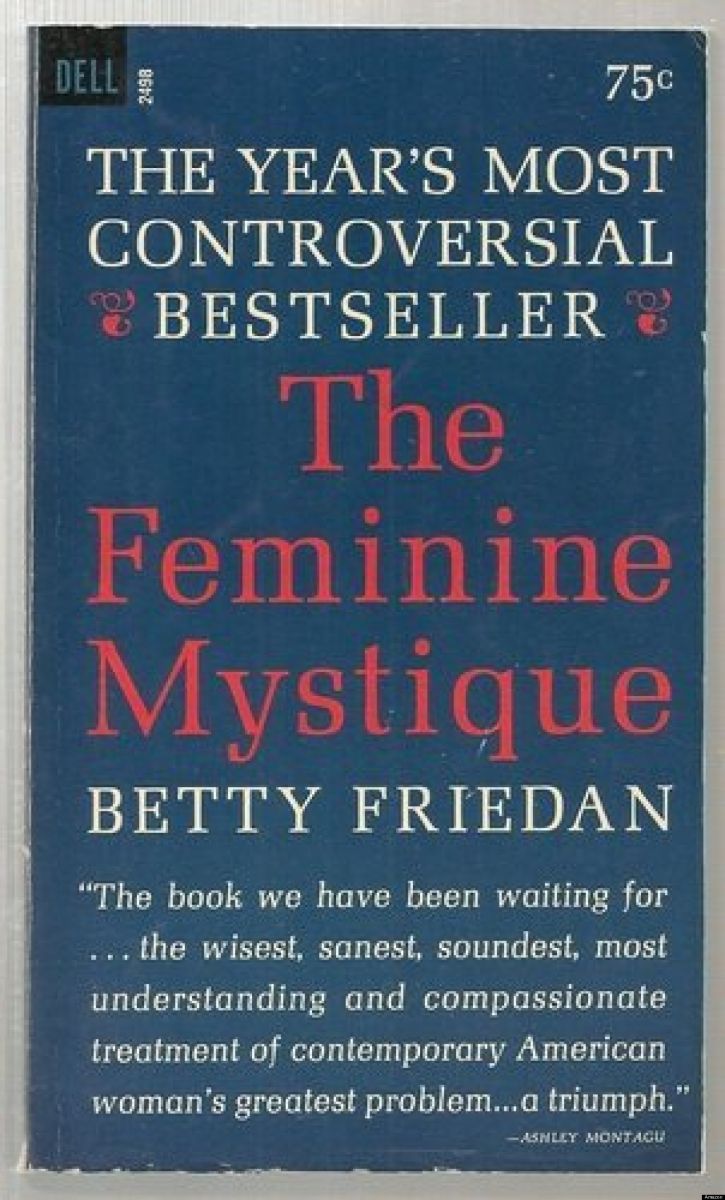

During the 1960s a significant movement began to emerge in the United States and elsewhere, with the publication of books on feminist theory such as The Second Sex (1953) by Simone de Beauvoir and The Feminine Mystique (1963) by Betty Friedan. There was, at the time, a general climate that was favourable to minority rights and anti-discrimination movements and, as a result of emerging work on women’s rights, many militant women's groups were formed.

The Feminine Mystique (1963) is regarded as the book that marked the beginning of the Women’s Liberation Movement. Friedan explored the unhappiness of mid-twentieth century women, describing it as ‘the problem that has no name’ and arguing that women felt disempowered because they were forced to be subservient to men financially, mentally, physically, and intellectually. Friedan used the term ‘feminine mystique’ to describe an idealised female image to which women tried (and failed) to conform.

The Feminine Mystique (1963) is regarded as the book that marked the beginning of the Women’s Liberation Movement. Friedan explored the unhappiness of mid-twentieth century women, describing it as ‘the problem that has no name’ and arguing that women felt disempowered because they were forced to be subservient to men financially, mentally, physically, and intellectually. Friedan used the term ‘feminine mystique’ to describe an idealised female image to which women tried (and failed) to conform.

In the post-World War II United States, women were expected to be nothing other than wives, mothers and home makers. Being relegated to a subservient role, Friedan argued, had a detrimental effect on women’s self-esteem.

In the early twentieth century, women had often married late after pursuing careers and education, but by the 1950s fewer women went to college and the average age of marriage had fallen sharply. The idea Betty Friedan expressed in The Feminine Mystique was that if women could escape the restrictions of traditional ideas of femininity, they could begin to enjoy being women.

The Feminine Mystique became an international bestseller and launched the so-called second-wave feminist movement. A body of feminist literature followed:

- Kate Millett's Sexual Politics

- Germaine Greer's The Female Eunuch

- Bell Hooks' Ain't I a Woman?

- Novels by Angela Carter and Marilyn French

- Memoirs and poems by Maya Angelou, Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich

- Alice Walker’s The Color Purple.

Black women and the feminist movement

The experiences of white, middle class women were foregrounded in much of the period’s feminist literature, which was predominantly written by white female authors. As a result, black women's experiences of sexism and discrimination were largely ignored.

Black women were active in both the black liberation movements and the emerging women’s movement, but were often discriminated against sexually and racially. Although neither all the black men nor all the white women in their respective movements were sexist and racist, enough of those with powerful influence were able to make the lives of black women in these groups very difficult.

Because black female experiences were shaped and determined by generations of suffering from slavery and segregation, many women of colour found it difficult to identify with white feminist ideology and identified more closely with Alice Walker’s redefinition of feminism as ‘womanism’.

Alice Walker and womanism

The invention of the term is attributed to Alice Walker in her 1979 short story Coming Apart, although some sources suggest that it first appeared in Walker’s In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (1983).

Walker defines a ‘womanist’ woman as someone who:

- Displays the characteristics of a woman, as opposed to those of a young girl

- Is mature or grown up

- Can love other women and/or individual men, either sexually or platonically

- Appreciates female emotions, female culture and female strength of character

- Loves the arts, nature and all things of the spirit.

Some feminist theory presents men as antagonists in the struggle for gender equality in a predominantly patriarchal society, thus making feminism a separatist ideology.

Womanism, on the other hand, affirms and emphasises the importance of women’s relationships with men, and Walker suggests that social survival rests upon the achievement of stability in family life.

The significance of purple

Walker used an inventive analogy to compare and contrast feminism and womanism by describing feminism as ‘pink’ and womanism as ‘purple’. Her intention was presumably to imply that the deeper colour signifies a greater ideological power than the lighter colour.