Gerard Manley Hopkins, selected poems Contents

- As Kingfishers Catch Fire

- Binsey Poplars

- The Blessed Virgin Mary Compared to the Air We Breathe

- Carrion Comfort

- Duns Scotus' Oxford

- God's Grandeur

- Harry Ploughman

- Henry Purcell

- Hurrahing in Harvest

- Inversnaid

- I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- Synopsis of I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- Commentary on I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- Language and tone in I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- Structure and versification in I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- Imagery and symbolism in I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- Themes in I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- Synopsis of The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- Commentary on The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- Language and tone in The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- Structure and versification in The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- Imagery and symbolism in The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- Themes in The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- The May Magnificat

- My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- Synopsis of My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- Commentary on My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- Language and tone in My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- Structure and versification in My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- Imagery and symbolism in My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- Themes in My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- No Worst, There is None

- Patience, Hard Thing!

- Pied Beauty

- The Sea and the Skylark

- Spelt from Sibyl's Leaves

- Spring

- Spring and Fall

- St. Alphonsus Rodriguez

- The Starlight Night

- That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the Comfort of the Resurrection

- Synopsis of That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire

- Commentary on That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire

- Language and tone in That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire

- Structure and versification in That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire

- Imagery and symbolism in That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire

- Themes in That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire

- Thou Art Indeed Just, Lord

- Tom's Garland

- To Seem the Stranger

- To What Serves Mortal Beauty

- The Windhover

- The Wreck of the Deutschland

- Beauty and its purpose

- The beauty, variety and uniqueness of nature

- Christ's beauty

- Conservation and renewal of nature

- God's sovereignty

- The grace of ordinary life

- Mary as a channel of grace

- Nature as God's book

- Night, the dark night of the soul

- Serving God

- Suffering and faith

- The temptation to despair

- The ugliness of modern life

- Understanding evil in a world God has made

Gerard Manley Hopkins - Life as a Jesuit

Hopkins' poetry rejected

As a mark of his determination to enter the Jesuit order, Hopkins ceremoniously burned all his poems. He termed it ‘the Slaughter of the Innocents’.

Saved by Robert Bridges

Fortunately, Hopkins had already sent some of the better poems to a University friend, Robert Bridges: some seventy survived in this way, together with numerous fragments. Although they are not covered by this guide, they do show some of the marks of Hopkins’ later poems.

Fortunately, Hopkins had already sent some of the better poems to a University friend, Robert Bridges: some seventy survived in this way, together with numerous fragments. Although they are not covered by this guide, they do show some of the marks of Hopkins’ later poems.

Hopkins sent most of his later poems to Bridges and, after Hopkins’ death, it was Bridges who finally got them edited and published. Bridges himself was training to be a doctor, though later on he also became a published poet. Hopkins and he corresponded a good deal about poetry, though they were worlds apart in terms of their religious views.

Hopkins' Jesuit training

On September 7, 1868, Hopkins started his Jesuit training as a novice, at Manresa House in Roehampton, on the edge of Richmond Park, London. It was a long and arduous training, interspersed with periods of parish work.

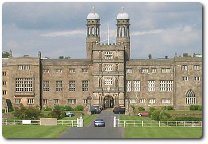

Once he had finished his novitiate, he went on to Stonyhurst in Lancashire, a Jesuit Theological College, though now it is a  Catholic public school. It was his first stay in Lancashire and he seems to have enjoyed the countryside, though the mill towns depressed him tremendously, especially the poverty of many of the workers. It was the first time in his rather privileged life he had come face to face with such conditions.

Catholic public school. It was his first stay in Lancashire and he seems to have enjoyed the countryside, though the mill towns depressed him tremendously, especially the poverty of many of the workers. It was the first time in his rather privileged life he had come face to face with such conditions.

In 1873, he briefly returned to Manresa House to do some lecturing in rhetoric (the study of language as a medium of persuasion). Here, he did a lot more focused thinking about English poetry.

In 1874, Hopkins was moved to North Wales to complete this theological training, where he had an opportunity to put his thinking about poetry into practice. From the time of his burning his poems till 1875, he had written no poetry. He felt that if it was God’s will for him to do so, one of his superiors would ask him.

He seems to have been happier in Wales than in most other places during his priesthood. His time there culminated in his ordination as a fully-fledged priest on September 23, 1877. He was 33 years old.

Hopkins' return to poetic expression

The sinking of a ship in the North Sea off the Thames Estuary proved the unlikely occasion of being asked to write poetry again. The S.S.Deutschland had been carrying five Catholic nuns into exile from Germany, from where they had been banished. They drowned, together with over a third of the people on board. Hopkins’ superior, perhaps in passing, said the event ought to be written about. Hopkins took the hint and The Wreck of the Deutschland was the result, the first example of Hopkins’ ‘new style’ poetry.