Gerard Manley Hopkins, selected poems Contents

- As Kingfishers Catch Fire

- Binsey Poplars

- The Blessed Virgin Mary Compared to the Air We Breathe

- Carrion Comfort

- Duns Scotus' Oxford

- God's Grandeur

- Harry Ploughman

- Henry Purcell

- Hurrahing in Harvest

- Inversnaid

- I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- Synopsis of I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- Commentary on I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- Language and tone in I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- Structure and versification in I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- Imagery and symbolism in I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- Themes in I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark

- The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- Synopsis of The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- Commentary on The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- Language and tone in The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- Structure and versification in The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- Imagery and symbolism in The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- Themes in The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

- The May Magnificat

- My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- Synopsis of My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- Commentary on My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- Language and tone in My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- Structure and versification in My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- Imagery and symbolism in My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- Themes in My Own Heart, Let Me Have More Pity On

- No Worst, There is None

- Patience, Hard Thing!

- Pied Beauty

- The Sea and the Skylark

- Spelt from Sibyl's Leaves

- Spring

- Spring and Fall

- St. Alphonsus Rodriguez

- The Starlight Night

- That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the Comfort of the Resurrection

- Synopsis of That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire

- Commentary on That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire

- Language and tone in That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire

- Structure and versification in That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire

- Imagery and symbolism in That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire

- Themes in That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire

- Thou Art Indeed Just, Lord

- Tom's Garland

- To Seem the Stranger

- To What Serves Mortal Beauty

- The Windhover

- The Wreck of the Deutschland

- Beauty and its purpose

- The beauty, variety and uniqueness of nature

- Christ's beauty

- Conservation and renewal of nature

- God's sovereignty

- The grace of ordinary life

- Mary as a channel of grace

- Nature as God's book

- Night, the dark night of the soul

- Serving God

- Suffering and faith

- The temptation to despair

- The ugliness of modern life

- Understanding evil in a world God has made

Religion

A religious society

A significant difference between modern British society compared to Victorian society is in the importance of religion, both in terms of actual churchgoing and in religious talk and debate. In the U.S.A. today, the situation is more like that of Victorian Britain:

- churches on most street corners

- a good percentage of the population attends church on a Sunday morning

- preachers get a wide hearing, if not in halls and public meetings, then on television and radio.

The Church of England

In Victorian England the Church of England was still the dominant church, mainly because it was the state church, although in terms of numbers, the combined membership of the chapels or nonconformist churches, (Baptist, Methodist etc.), was approaching that of the Church of England.

In the eighteenth century, the Church of England had been very formal and rather moribund in its religious practice. In the first quarter of the nineteenth century, an Evangelical Movement had begun in the Anglican church, enthused by the more recent Methodist movement. Sometimes, this is referred to as Low Church Anglicanism.

Evangelicalism

Among other things, this style of Christianity promoted

However, it never really penetrated the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, the two main centres of learning in England, where most of the nation's political and church leaders were educated. Until well into the nineteenth century, someone could not be a student at either university if they were not an Anglican. The two universities had become real bastions of die-hard Anglicanism, Oxford even more so than Cambridge.

A different way of worshipping

In 1833, a series of tracts (leaflets arguing a point of view) entitled ‘Tracts for the Times' were circulated at Oxford, some by John Keble, an Anglican clergyman who wanted an even stricter observance of the rituals laid down in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. The tracts, which continued to be published till 1841, wanted the Church of England to become more like the Roman Catholic church, though not to accept the authority of the Pope, who was the head of the Catholic Church.

- To opponents, this meant putting the clock back to before the time of the Reformation

- To others, however, it meant restoring a proper sense of awe to church services and enhancing them with greater beauty and drama. For such individuals it also meant a new devotion to prayer, leading to a new spiritual energy.

The Oxford Movement

An influential group of people accepted the challenge of the tracts. They became known as Tractarians, or Puseyites after their leader, Edward Pusey, and the movement was sometimes called the Oxford Movement or the High Church revival. To-day the term Anglo-Catholic is often used for Anglicans who like to align their practice to that of the Roman Catholic Church.

Typically, ‘High Church' Anglicans put a great stress on:

- ritual in worship

- observing the seasons of the church year

- saints' days

- ornate robes worn by the clergy and choir

- candles, incense and other aesthetic considerations.

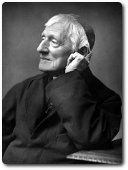

John Henry Newman

One of the early Tractarians and the writer of the very first tract was John Henry Newman. In 1845, to the Tractarians' dismay, Newman decided to become a Roman Catholic. In addition to experiencing a distinct religious experience, he was intellectually convinced that the logic of becoming more closely aligned to Roman Catholic practice was to go ‘all the way'. He was not deterred by the question of the Pope's authority. A number of his friends went ‘over to Rome', as it was termed, with him.

One of the early Tractarians and the writer of the very first tract was John Henry Newman. In 1845, to the Tractarians' dismay, Newman decided to become a Roman Catholic. In addition to experiencing a distinct religious experience, he was intellectually convinced that the logic of becoming more closely aligned to Roman Catholic practice was to go ‘all the way'. He was not deterred by the question of the Pope's authority. A number of his friends went ‘over to Rome', as it was termed, with him.